Introduction

Urinary incontinence (UI) is a medical disorder that causes involuntary urine leakage from the bladder. It is a widespread disease that can affect people of all ages, although it affects females more than males.

- UI might range from minor dribbling to full bladder control failure. Several causes can contribute to the disease, including weak pelvic muscles, nerve damage, hormonal changes, prostate issues, drugs, and certain medical illnesses.

- This disorder is more common in the elderly, affecting both health and quality of life, although it can also affect younger persons.

- The International Continence Society defines urinary incontinence as the involuntary leakage of pee that causes a sanitary or social concern for the individual. Urinary incontinence can be considered a symptom described by the patient, a sign seen on examination, and a condition.

- Because no clear etiology exists, urinary incontinence should not be considered a disease; most individual instances are likely multifactorial in origin. Urinary incontinence etiologies are numerous and, in many situations, poorly understood.

- It is a widespread condition that is frequently underreported owing to the embarrassment and social stigma associated with it. UI can have a substantial impact on a person’s quality of life, but it can be considerably improved with proper assessment, treatment, and management.

Incidence

- Urinary incontinence is a common but underdiagnosed and underreported issue that affects 38-55% of women over the age of 60 and 50-84% of the elderly in long-term care institutions.

- Females are more than twice as likely as males to experience urine incontinence at any age.

- It is estimated that over 423 million persons (20 and older) globally suffer from urine incontinence.

- Everyday urine incontinence affects 9% to 39% of women over the age of 60.

Classification of Urinary Incontinence

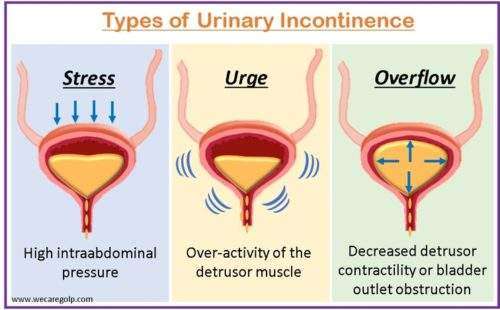

Stress urinary incontinence (SUI)

- Stress urinary incontinence, caused by urethral sphincter and/or pelvic floor weakness, is the involuntary leakage of urine during physical activities such as coughing, sneezing, or exercise.

- It is caused by weakness or damage to the muscles and tissues that support the bladder and urethra.

- Stress incontinence is more common in women, especially after childbirth and menopause.

- This kind of incontinence can affect young women who participate in sports.

Urge urinary incontinence (UUI)

- Urge incontinence is the involuntary leakage of urine, which may be preceded or accompanied (but may also be asymptomatic) by a feeling of urinary urgency. This condition is caused by the over-activity of the detrusor muscle.

- It is caused by involuntary contractions of the bladder muscles, which can be triggered by various factors, including bladder infections, neurological disorders, and certain medications.

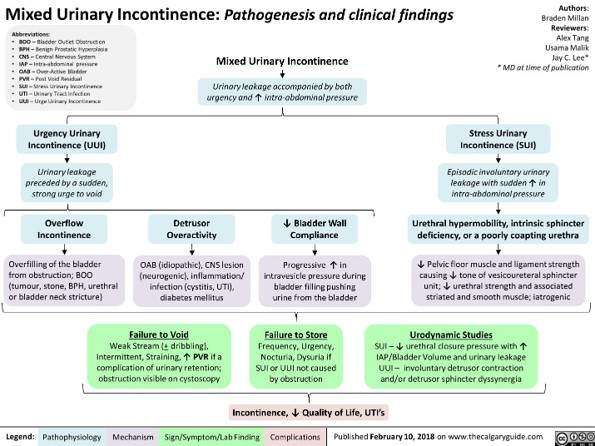

Mixed urinary incontinence

- Mixed incontinence includes both stress and urge incontinence.

- It is common in women, particularly in those who have experienced childbirth or menopause.

Overflow urinary incontinence

- The involuntary leakage of urine from an overextended bladder as a result of decreased detrusor contractility and/or blockage of the bladder outlet is known as overflow urinary incontinence.

- Detrusor function may be hampered by neurological conditions such as multiple sclerosis (MS), diabetes, and spinal cord injuries.

- Among other things, pelvic organ prolapses (bladder, rectum, or uterine prolapse) and external compression from abdominal or pelvic masses can result in bladder outlet blockage.

- Male benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is a typical cause.

Functional incontinence

- Functional incontinence is the inability to reach the bathroom in time due to physical or cognitive limitations, such as mobility issues, dementia, or communication barriers.

- It is associated with reduced mobility and cognitive ability.

- Lower urinary tract function is unaffected by functional incontinence, but patients may struggle to recognize when they need to go to the bathroom or may find it difficult to get there on time due to impaired mobility or cognitive function.

Causes of Urinary Incontinence

- Urethral hypermobility caused by insufficient anatomic pelvic support is the most prevalent cause.

- Postmenopausal estrogen loss, delivery, surgery, or certain conditions that alter tissue strength might cause women to lose this pelvic support.

- Intrinsic sphincter deficit, which can develop from age, like pelvic trauma, surgery (e.g., hysterectomy, urethropexy, pubovaginal sling), or neurologic malfunction, is a less prevalent cause.

- Neurological conditions: Multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, and spinal cord injuries are a few neurological diseases that can interfere with the nerves that regulate the bladder and cause urine incontinence.

- Weakening of connective tissue, genitourinary atrophy brought on by hypoestrogenism, increased prevalence of associated medical illnesses, increased nocturnal diuresis, and impairments in mobility and cognitive function are all contributing causes to aging-related urine incontinence.

- Prostatitis and BPH may be the causes of male urinary incontinence.

- Caffeine, alcohol, and spicy meals, among others, can irritate the bladder

- In older persons, vitamin D insufficiency has been recognized as a risk factor for urine incontinence.

- Obesity, straining at stool, strenuous manual labor, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and smoking are all risk factors for developing incontinence

- In addition to urinary tract infection (UTI), bladder cancer, bladder stones, and foreign substances can irritate the bladder and cause involuntary bladder spasms and incontinence.

- Several drugs, either directly or indirectly, lead to urinary incontinence (anticholinergics, diuretics, alpha-antagonist, sedatives, calcium channel blockers)

- Hospitalized patients and elderly individuals both frequently have transient incontinence.

For most reversible causes of incontinence, the acronym DIAPPERS is helpful:

- D – Delirium or severe confusion

- I – Illness (symptomatic UTI)

- A – Urethritis or atrophic vaginitis

- P – Pharmaceutical substances

- P: Psychiatric conditions (depression, behavioral disturbances)

- E: Excess urination (due to diuretics, peripheral edema, excessive fluid consumption, alcoholic or caffeinated beverages, congestive heart failure, or metabolic problems such as hyperglycemia or hypercalcemia)

- R – Restricted mobility (limits ability to reach a bathroom in time)

- S – Impaction of stools

Signs and Symptoms of Urinary Incontinence

- Leakage of urine

- Poor urinary stream

- Irritation in the perineal area

- Urinary urgency/frequency

- Nocturia (frequent urination at night)

- Trouble initiating or halting the flow of urine

- Bedwetting in previously toilet-trained children

- Dribbling of urine while engaged in physical activity or exertion such as coughing, sneezing, or laughing

- Recurrent urinary tract infections

- Dysuria (pain during urination)

- A feeling of incomplete bladder emptying

- Poor quality of life (ashamed, embarrassed, and isolated)

Pathophysiology of Urinary Incontinence

- The synchronization of various physiological systems is necessary for urination. The spinal cord receives information about bladder volume through somatic and autonomic neurons, which causes the motor output innervating the detrusor, sphincter, and bladder musculature to change in response.

- The brainstem helps people urinate by coordinating the relaxation of the urethral sphincter and contraction of the detrusor muscle, whereas the cerebral cortex mostly acts as an inhibitor.

- Sympathetic tone reduces parasympathetic tone when the bladder fills, helping to close the bladder neck and relax the bladder dome. The striated periurethral muscles and the pelvic floor musculature are both kept toned concurrently via somatic innervation.

- The muscles of the bladder and periurethral region experience a drop in sympathetic and somatic tones during urination, which lowers urethral resistance.

- Bladder contraction is brought on by an increase in cholinergic parasympathetic tone.

- When bladder pressure is greater than urethral resistance, urine flows.

- The first desire to urinate often strikes between 150 and 300 mL of bladder volume, which is within the range of normal bladder capacity of 300–500 mL.

- When micturition physiology, functional toileting abilities, or both are impaired, incontinence results.

- Many forms of incontinence have various underlying pathologies

Pathophysiology of Stress Urinary Incontinence

- SUI is characterized by a loss of urethral support, leading to an inability to maintain continence.

- Factors such as pregnancy, childbirth, or menopause can weaken the pelvic floor muscles and ligaments that support the urethra, resulting in a decrease in urethral closure pressure and an increase in urethral mobility.

- These changes lead to urine leakage during increased intra-abdominal pressure.

Pathophysiology of Urge Urinary Incontinence

- Urge incontinence can be caused by detrusor myopathy, neuropathy, or a mix of the two. Idiopathic urge incontinence occurs when the identified reason is unknown.

- Urge incontinence is characterized by unrestrained bladder contractions produced by irritation or lack of neurologic control of bladder contractions.

- Weak detrusor compliance prevents the bladder from stretching, which raises intravesical pressure. In addition, there is pain experienced when filling and a capacity limitation.

- This frequently results after catheterization for extended periods of time or pelvic radiation. It is thought that bladder hypersensitivity and the urothelium’s sensory function are related.

- A crucial modulator of bladder function, the urothelium, has recently been shown to have a role in urothelial inflammation and infection, which can result in an overactive bladder with or without urgency.

Pathophysiology of mixed urinary incontinence

The diagram below explains the pathophysiology of mixed urinary incontinence.

Diagnosis of Urinary Incontinence

The diagnosis of UI usually involves a thorough medical history, physical examination, and diagnostic tests.

Medical history

- According to a study published in the International Journal of Urology, obtaining a detailed medical history is essential in the diagnosis of urinary incontinence.

- The history should include

- Information on the patient’s symptoms

- Frequency and severity of urinary leakage

- Underlying medical conditions

- Medication use

Physical examination

- A physical examination is another essential component of the diagnostic workup for urinary incontinence.

- The examination should include

- An assessment of pelvic floor muscle strength

- A vaginal or rectal examination

- A neurologic examination

- According to a study that was published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, a physical examination is essential for making the diagnosis of stress urinary incontinence because it can identify

- The presence of pelvic organ prolapses

- Urethral hypermobility

- Other potential causes of urinary leakage

Diagnostic tests

- A dipstick urinalysis should be conducted to check for

- Hematuria

- Glycosuria and

- Infection symptoms

- Serum creatinine is normally not required; however, it may be evaluated if the patient has a history of

- Recurrent UTI

- Urine retention

- Renal obstruction.

Bladder diary

- A bladder diary should be kept by the patient.

- The diary should be kept for three days and include information such as

- The amount and kind of fluids drank

- How frequently do they urinate

- Any bouts of urgency

- Any incidents of incontinence

- Number of used pads/clothing

- A bladder diary has been demonstrated to be a valid technique for evaluating

- Frequency

- Incontinence and

- Treatment response

Post-void residual bladder volume

- Patients with substantial voiding symptoms, recurrent UTI, symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse, or bladder distension should have their post-void residual bladder volume measured.

- This should be done using a bladder ultrasound, which will necessitate a referral to clinics that do not have bladder scanning technology.

- In-out catheterization can be performed to evaluate residual urine volume in the bladder if bladder scanning is not possible or if urinary retention is observed during the test.

Urodynamic testing

- In secondary care, urodynamic testing may be used.

- It assesses the ability of the bladder and urethra to hold and discharge urine.

- The test typically captures flow rate, residual urine, and capacity, and can detect involuntary spasms that cause leakage pre, during, or after voiding.

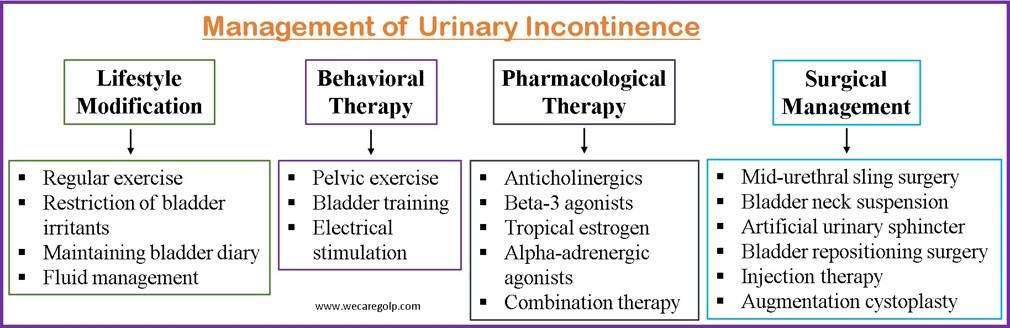

Treatment of Urinary Incontinence

- The purpose of urinary incontinence therapy is to

- Improve the quality of life

- Correct underlying medical issues

- Educate patients and

- Avoid consequences

- Urinary incontinence is often treated with a mix of

- Lifestyle changes

- Behavioral therapy

- Pharmaceutical treatments and

- Surgery (in rare circumstances)

- The strategy taken will be determined by the kind and intensity of incontinence.

Lifestyle Modifications

Lifestyle modification is the first-line treatment for urinary incontinence.

- Exercise regularly, weight reduction

- Restriction of bladder irritants like caffeine, alcohol, and citrus juices

- Maintaining bladder diary

- Fluid management

Behavioral Therapies

- Pelvic floor muscle exercises (Kegels)

- Bladder training

- Biofeedback, which teaches people how to regulate their bladder muscles with the use of electrical monitoring equipment

- Electrical stimulation increases bladder control by stimulating the pelvic floor muscles with a little electric current.

Pharmacological Treatment

Anticholinergics

- Urge incontinence is treated with anticholinergic medications such as

- Oxybutynin

- Tolterodine

- Solifenacin

- Darifenacin

- These medications function by inhibiting the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, which activates the bladder muscles.

- Nevertheless, they may result in adverse consequences including dry mouth, constipation, and visual haze.

Beta-3 agonists

- One of the beta-3 agonists for urge incontinence is Mirabegron.

- It increases the bladder’s ability to retain urine by reducing bladder muscle tension.

- It is less likely to induce adverse effects, although it can raise blood pressure.

Topical estrogen

- The treatment for stress incontinence, which is brought on by weak pelvic floor muscles, is topical estrogen creams or patches.

- Estrogen contributes to increased vaginal tissue thickness and tone, which can lessen the severity of stress incontinence.

- Nevertheless, women who have a history of breast cancer should take topical estrogen with care.

Alpha-adrenergic agonists

- An alpha-adrenergic agonist called duloxetine is used to treat stress incontinence.

- It functions by making the urethral sphincter muscles more toned, which can stop urine leakage.

- Nevertheless, adverse effects of duloxetine might include nausea, dry mouth, and dizziness.

Combination therapy

- To treat their urine incontinence, some people may need a mix of medications.

- An anticholinergic medication plus a topical estrogen cream, for instance, may be beneficial in treating a patient who has both urge and stress incontinence.

Surgical Treatment

Mid-urethral sling surgery

- This is the most used surgical treatment for female urinary incontinence.

- In order to support the urethra, the surgeon makes a sling from synthetic mesh material or the patient’s own tissue.

- The sling supports the urethra and stops urine flow by acting like a hammock.

- The goal is to strengthen the pelvic floor muscles that are lacking and provide a “backboard” or “hammock” of support beneath the urethra.

Bladder neck suspension

- A surgeon performs the Marshall-Marchetti-Krantz (MMK) technique, often referred to as bladder neck suspension surgery or retropubic suspension, in a hospital environment.

- A long, thin, flexible tube (catheter) is introduced into the bladder through the small tube (urethra) that empties the body’s urine while the patient is under general anesthesia.

- The bladder is visible after an abdominal incision has been done.

- The tissues around the bladder are segregated.

- These tissues close to the bladder neck and urethra are stitched (sutured).

- The sutures are attached to the pubic bone or the fascia behind the pubic bone after the urethra is lifted.

- The bladder neck is supported by the sutures, which aid the patient in gaining control over urine flow.

Artificial urinary sphincter

- Men with severe urine incontinence brought on by a weak or injured urinary sphincter have this device implanted.

- The contraption consists of a cuff that fits around the urethra and a tiny pump that is positioned in the scrotum.

- The device’s manual controls allow the patient to manually open or seal the urethra to let urine through or stop leaks.

- Rarely, a surgeon would insert an artificial urinary sphincter, a sac with a doughnut form that surrounds the urethra.

- The sac is filled with a fluid that swells as it fills, sealing the urethra shut.

- The artificial sphincter may be released by depressing a valve that is installed beneath the skin.

- As a result, the urethra’s pressure is released, allowing the bladder to release urine.

Bladder repositioning surgery

- The bladder tends to descend into the vagina in most cases of stress incontinence in women.

- Consequently, raising the bladder to a more natural position is a frequent surgery for stress incontinence.

- The surgeon lifts the bladder and attaches it with a string tied to muscle, ligament, or bone while operating through an incision in the vagina or abdomen.

- The surgeon may use a large sling to restrain the bladder in situations of severe stress incontinence.

- In addition to supporting the bladder, this also compresses the urethra’s top and bottom, further restricting leakage.

Injection therapy

- To form a seal that stops urine leakage, a bulking substance, such as collagen, is injected into the tissue around the urethra during this surgery.

- Typically, only individuals with mild to moderate stress urinary incontinence are candidates for this surgery.

Augmentation cystoplasty

- Augmentation cystoplasty (bladder augmentation) is a surgical procedure performed when a person does not have adequate bladder capacity or detrusor compliance.

- For some people, it may provide a safe and useful reservoir that allows urinary continence and halts upper urinary tract degeneration.

Complications of Urinary Incontinence

- Skin problems including irritation, redness, sores, infections, and breakdown of the skin

- Urinary tract infections

- Reduced quality of life (embarrassment, anxiety, and depression.)

- Sleep disturbances, frequent awakenings during the night, fatigue

- Falls and fractures

- Pressure ulcers

- Sexual dysfunction

- Trauma and infections

- Decreased physical activity

Prevention of Urinary Incontinence

- Maintaining a healthy body weight: One factor contributing to incontinence might be being overweight. Incontinence can be prevented by maintaining a balanced diet and engaging in regular exercise.

- Practice pelvic floor exercises: Kegel exercises are a quick and easy approach to strengthening pelvic floor muscles. These exercises involve raising, holding, and releasing the pelvic floor muscles.

- Drink plenty of water: Constipation or bladder discomfort might result from dehydration. This can put extra pressure or strain on the bladder. Staying hydrated can prevent UTIs, thus limiting the aggravation of urinary incontinence.

- A high-fiber diet can help avoid incontinence.

- Quit smoking, and limit caffeine and alcohol: These agents irritate the bladder and weaken the pelvic floor muscles. Thus, restricting smoking, caffeine, and alcohol can help prevent urinary incontinence.

- Treat underlying medical conditions like diabetes.

- Practice good toilet habits: Healthy bowel and bladder habits can help avoid bladder and bowel disorders. The risk of incontinence is increased when an individual holds urine for longer periods.

Prognosis

- Patients respond differently to care and management. Several therapy methods should be used to provide the best symptom management in people whose symptoms cannot be fully removed. The current treatment has a significant positive effect on urinary continence with decreased/limited morbidity.

- When the underlying reason is resolved, incontinence may occasionally become a transient problem. When patients have a problem like a urinary tract infection, urinary continence is a major problem. If UTI is treated, frequent urine and leakage issues are usually resolved. This also applies to some pregnant women with bladder control issues. Some reasons for incontinence, however, are chronic and linked to diseases that require ongoing care. Incontinence may last a long time if you have a chronic illness like diabetes or multiple sclerosis.

- Lifestyle modifications, bladder training, Kegel exercises, and restricting caffeine intake can significantly improve the prognosis of urinary incontinence.

Summary

- The involuntary leakage of urine is known as urinary incontinence (UI). Although it can affect younger people as well, this disorder affects health and quality of life more frequently in the elderly.

- UI can be classified as stress incontinence, urge incontinence, mixed incontinence, and overflow incontinence. Stress urinary incontinence, caused by urethral sphincter and/or pelvic floor weakness, is the involuntary leakage of urine during physical activities such as coughing, sneezing, or exercise. Urge urinary incontinence is defined as involuntary urine leaking that is preceded or accompanied by a sensation of urinary urgency. Stress and urge incontinence both belong to mixed incontinence.

- Urinary incontinence can be caused by both urological and nonurological factors. Urological reasons for bladder or urethral dysfunction might include detrusor overactivity, inadequate bladder compliance, urethral hypermobility, or intrinsic sphincter inadequacy.

- Treatment strategies include lifestyle modifications, behavioral therapy, pharmacological therapy, and rarely surgical management.

References

- Abrams, P., Andersson, K. E., Birder, L., Brubaker, L., Cardozo, L., Chapple, C., Cottenden, A., Davila, W., de Ridder, D., Dmochowski, R., Drake, M., Dubeau, C., Fry, C., Hanno, P., Haylen, B., Herschorn, S., Hosker, G., Kelleher, C., Koelbl, H., … Wein, A. (2010). Fourth International Consultation on Incontinence Recommendations of the International Scientific Committee: Evaluation and treatment of urinary incontinence, pelvic organ prolapses, and fecal incontinence. Neurourology and Urodynamics, 29(1), 213-240. https://doi.org/10.1002/nau.20870

- Aoki, Y., Brown, H. W., Brubaker, L., Cornu, J. N., Daly, J. O., & Cartwright, R. (2017). Urinary incontinence in women. Nature reviews Disease primers, 3(1), 1-20. doi:10.1038/nrdp.2017.42.

- Burgio, K. L., Goode, P. S., Locher, J. L., Umlauf, M. G., Roth, D. L., Richter, H. E., … & Lloyd, L. K. (2002). Behavioral training with and without biofeedback in the treatment of urge incontinence in older women: a randomized controlled trial. Jama, 288(18), 2293-2299. doi:10.1001/jama.288.18.2293

- Dumoulin, C., Hay-Smith, J., Frawley, H., & McClurg, D. (2018). Pelvic floor muscle training versus no treatment, or inactive control treatments, for urinary incontinence in women: A Cochrane systematic review summary. Neurourology and Urodynamics, 37(8), 2744-2746. https://doi.org/10.1002/nau.23767

- Forde, J. C., Chughtai, B., Cea, M., Stone, B. V., Te, A., & Bishop, T. F. (2017). Trends in ambulatory management of urinary incontinence in women in the United States. Urogynecology, 23(4), 250-255. DOI: 10.1097/SPV.0000000000000365

- Hunskaar, S., Lose, G., Sykes, D., & Voss, S. (2004). The prevalence of urinary incontinence in women in four European countries. BJU International, 93(3), 324-330. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-410X.2003.04609.x

- Lightner, D. J., Gomelsky, A., Souter, L., & Vasavada, S. P. (2019). Diagnosis and treatment of overactive bladder (non-neurogenic) in adults: AUA/SUFU guideline amendment 2019. The Journal of urology, 202(3), 558-563. https://doi.org/10.1097/JU.0000000000000309

- Tran, L. N., & Puckett, Y. (2022). Urinary incontinence. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559095/#article-30850.s2

- Vasavada, S. P. (2021). Urinary Incontinence. Medscape. Retrieved on 2023, Feb 21 from https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/452289-overview