Introduction

Hematuria is defined as the presence of at least five red blood cells (RBCs)/high-power microscope field (HPF) in three successive centrifuged specimens taken at least seven days apart.

- Hematuria is the presence of blood in the urine. It can be asymptomatic or symptomatic, and it is often accompanied with other urinary tract disorders. The primary care provider is frequently the first to notice hematuria.

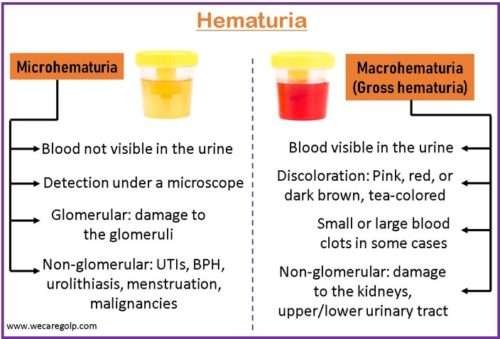

- It is one of the most concerning symptoms of renal disease. It can manifest as either macroscopic or microscopic as a result of glomerular or non-glomerular diseases.

- The clinical appearance and urine microscopy can distinguish glomerular hematuria from non-glomerular hematuria.

- Asymptomatic (isolated) hematuria usually does not require treatment. Treatment may be required in conditions associated with abnormal clinical, laboratory, or imaging findings, depending on the primary diagnosis.

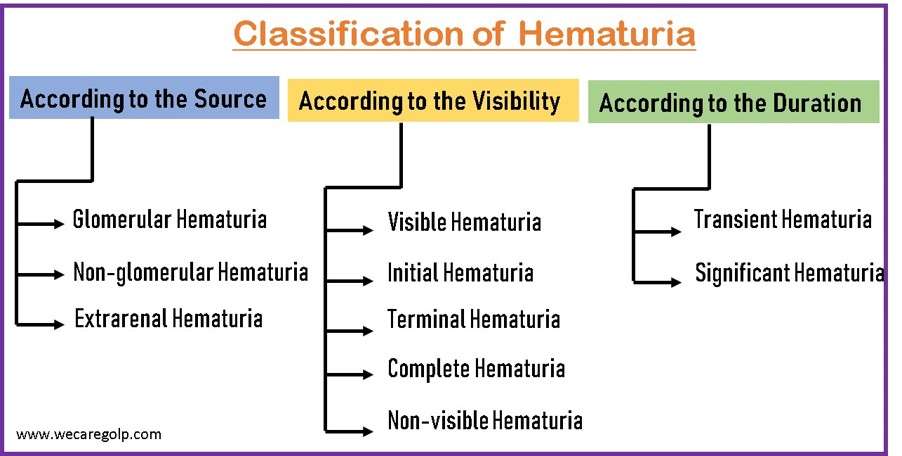

Classification of Hematuria

According to the Source

- Glomerular hematuria

- Non-glomerular hematuria

- Extrarenal hematuria

Glomerular hematuria

Glomerular hematuria is a significant sign of renal dysfunction.

- It is a common symptom of many kidney illnesses and can be classed as microscopic or macroscopic depending on its severity and the number of RBCs in the urine.

- Chronic glomerular microhematuria has a pathogenic role in the course of renal disease. Furthermore, in a large number of patients, extensive hematuria, or macrohematuria, increases acute kidney injury (AKI), with eventual deterioration of renal function.

- Hemoglobin, heme, or iron discharged from RBCs in the urine may induce

- Direct tubular cell damage,

- Oxidative stress,

- Pro-inflammatory cytokine production, and

- Other adverse effects.

- Dysmorphic (abnormally shaped) RBCs in urine are caused by RBC egression across the glomerular filtration barrier and suggest glomerular hematuria.

- The most prevalent cause of isolated glomerular microscopic hematuria is IgA nephropathy (without significant proteinuria). It is normally asymptomatic and often is diagnosed as an incidental finding.

Non-glomerular hematuria

- In non-glomerular hematuria, urinary RBCs have a more uniform size distribution and a bigger mean volume, with a higher peak volume than peripheral RBCs.

- It accounts for 90% of all hematuria cases.

- It is distinguished by the presence of isomorphic urinary erythrocytes without RBC casts or considerable proteinuria.

- It causes urine to be red or cherry colored. There may be clots or frank blood, and it can be initial, terminal, or continuous.

- Renal stones and pyelonephritis will both appear with episodic pain and fever. Polycystic kidney disease (PKD) is typically characterized by recurrent gross hematuria. Although the degree of proteinuria is related to the severity and development of renal disease, microscopic hematuria is not.

Extrarenal hematuria

- More than 60% of hematuria instances are caused by a source other than the kidney.

- The most prevalent nonmalignant causes outside the kidney are

According to the Visibility

- Visible hematuria

- Initial hematuria

- Terminal hematuria

- Total/complete hematuria

- Non-visible hematuria

Visible hematuria

- Visible (gross) hematuria is urine that is visibly discolored by blood or a blood clot. It might appear as red to dark urine or as fresh blood.

- 1 mL of blood may color 1 liter of urine.

- It, even if temporary or asymptomatic, may signal a serious disease condition and should always be investigated further.

- The workup of visible hematuria differs between children, people under the age of 35, and adults 35 and older.

- Patients with visible hematuria represent a greater risk of urologic cancer than those with non-visible hematuria.

- It is a presenting symptom in more than 66% of urologic cancer patients. Macrohematuria should always be investigated.

- Hematuria can be seen at concentrations as low as 1 mL of blood per liter of urine. Fresh arterial blood (bright red, ranging from pink to ketchup-colored) may be recognized from venous blood (dark red, Bordeaux red) and old blood by the color and intensity of the color (dark brown or black).

- Urine may occasionally be crimson or black due to myoglobinuria (from rhabdomyolysis) or hemoglobinuria (due to hemolysis). The presence of RBCs in the urine sediment, as revealed by qualitative and quantitative microscopy, confirms the diagnosis.

Initial hematuria

- Ita suggests anterior urethral hemorrhage (distal to the external sphincter).

- It indicates blood at the beginning of micturition with subsequent clearing. It suggests urethral disease.

Terminal hematuria

- It is described as the passage of clear urine containing blood or blood-stained urine at the end of the urine stream.

- It occurs at the end of the urinary tract and can be caused by the prostate, the bladder, or the trigonal system.

Total/complete hematuria

- In complete/total hematuria, bleeding is present throughout urination (problems in the bladder, ureter, or kidneys)

Non-visible hematuria

- The presence of three or more RBCs/HPF on a midstream, clean-catch urine sample is considered non-visible hematuria, also known as microhematuria.

- Clinically significant microscopic hematuria is defined as three or more RBCs/HPF (400), corresponding to 10-12 erythrocytes per microliter to automated analyzers (2), confirmed in two urinalysis tests when no benign etiology, such as menstruation, recent exercise, recent sexual activity, or recent urinary tract instrumentation, is present.

- The major reason for investigating non-visible hematuria, especially in the absence of lower urinary tract symptoms, is the possibility of urinary tract malignancy, which has a 5% chance of occurring.

- The causes of microscopic hematuria range from incidental to life-threatening urinary tract neoplasms.

According to the Duration

- Transient hematuria

- Significant hematuria

Transient hematuria

- In young patients, it is common and nearly invariably benign, and the cause is frequently unknown.

- A major exception to transient hematuria’s normally benign nature occurs in people over the age of 40, in whom even transient hematuria carries an elevated risk of cancer (assuming there is no evidence of glomerular bleeding)

Significant hematuria

- Significant/persistent hematuria is characterized by greater than three RBCs/HPF on three urinalyses or a single urinalysis with greater than 100 RBCs or gross hematuria.

- The causes are

- Urinary tract infections (UTIs),

- Urolithiasis,

- Malignancies,

- Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH),

- Nephropathies.

Causes of Hematuria

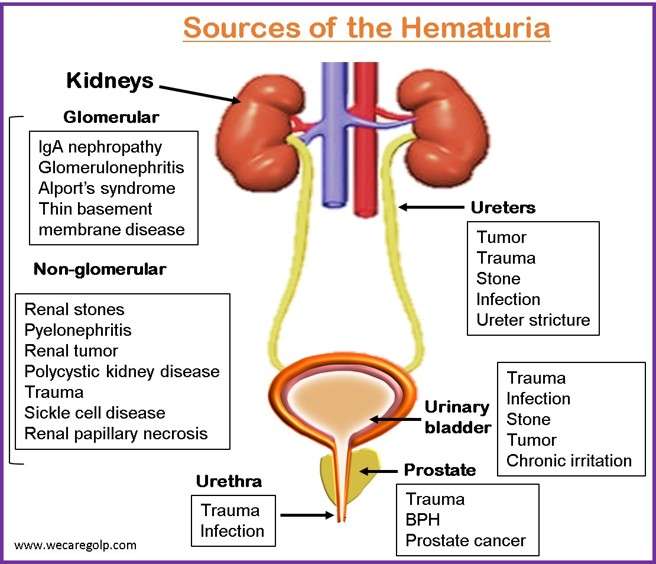

Glomerular cause

- Alport syndrome

- Mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis

- Nail-patella syndrome

- Other postinfectious glomerulonephrites: endocarditis, viral

- Thin basement membrane disease

- Post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis

- IgA nephropathy

- Pauci-immune glomerulonephritis

- Lupus nephritis

- Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis

- Goodpasture syndrome

- Nephrotic syndrome

- Polycystic kidney disease

Non-glomerular/ Extrarenal causes include:

- Febrile illness

- BPH

- Hypercalciuria

- Hyperuricosuria

- Renal cell carcinoma

- Solitary renal cyst

- Exercise

- Menstruation

- Nephrolithiasis

- Cystitis, urethritis, prostatitis

- Malignancy: bladder cancer, prostate cancer, renal cell carcinoma

- Genitourinary mucosal injury by instrumentation

- Trauma

- Bleeding tendency: use of blood thinners, thrombocytopenia, coagulopathy, and hematological disorders like sickle cell anemia.

Medications

- Aminoglycosides

- Cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan)

- Amitriptyline

- Diuretics

- Analgesics

- Oral contraceptives

- Anticonvulsants

- Penicillin (extended-spectrum)

- Aspirin

- Quinine (QM-260)

- Busulfan (Busulfex)

- Vincristine (Oncovin)

- Chlorpromazine (Thorazine)

- Warfarin (Coumadin)

Pathophysiology of Hematuria

Depending on the anatomic location in the urinary system where blood loss occurs, hematuria has a different pathogenesis.

Glomerular hematuria refers to blood that originates in the nephron.

- RBCs can reach the urinary area through the glomerulus or, in rare cases, through the renal tubule.

- The glomerular filtration barrier may be disrupted due to genetic or acquired defects in the structure and integrity of the glomerular capillary wall.

- These RBCs can become trapped in Tamm-Horsfall mucoprotein and appear as RBC casts in the urine. Finding casts in the urine indicates severe glomerular disease.

- However, in glomerular hematuria, casts may be absent and isolated RBCs may be the only observation.

- Proteinuria contributes to a glomerular source of blood loss.

Isolated hematuria is defined as hematuria without proteinuria or casts.

- Although isolated hematuria can occur in a few glomerular disorders, this observation is more consistent with extraglomerular hemorrhage.

- Anything that affects the uroepithelium, such as irritation, inflammation, or invasion, might result in normal-looking RBCs in the urine.

- Cancer, kidney stones, trauma, infection, and drugs are examples of such insults.

- Non-glomerular renal causes of blood loss, such as kidney tumors, renal cysts, infarction, and arteriovenous malformations, can also result in urinary blood loss.

Signs and Symptoms of Hematuria

Warning Signs

It becomes concerning when accompanied by:

- Gross hematuria

- Hypertension

- Proteinuria

- Elevated serum creatinine

Other significant signs

- Painful or asymptomatic.

- Crimson or dark-colored urine or passing blood clots.

- Flank pain

- Lower abdominal pain

- Painful urination

- Urinary urgency or frequency

- Fever

- Active menstruation

- Passing stone or grits

- Recent throat or skin infection

- Joint pains, oral ulcers, rash

- Hemoptysis

- Leg swelling

- Hearing loss

- Constitutional symptoms like weight loss, anorexia, cachexia

Diagnosis of Hematuria

Urinalysis

- It is the first and most important test to undertake.

- Patients with microscopic hematuria are initially identified by the urine dipstick test for blood. Urine sediment should be collected from the midstream of the first voiding in the morning and analyzed within 1-2 hours.

- To rule out hematuria, the number of RBCs in the urine sediment should be fewer than 2 or 3 per HPF.

- If there are more than 2 or 3 RBCs/HPF in the urine sediment, at least one additional urinalysis may be necessary to establish hematuria.

Urine microscopy

- The microscopic examination of urine not only verifies hematuria but also helps distinguish glomerular from non-glomerular causes of bleeding.

- RBCs in glomerular hematuria are subjected to substantial fluctuations in pH and osmotic pressure as they pass through the renal tubules, causing them to become dysmorphic. RBCs in non-glomerular hematuria are usually homogenous and normal in form. Proteinuria of 2+ or higher by dipstick also shows glomerular hematuria.

| Findings | Interpretation |

| Positive for urinary casts | Renal disease |

| Urinary crystals | Calculous disease |

| Dysmorphic red cells | Glomerular cause of hematuria |

| Atypical or malignant epithelial | Tumor |

Ultrasound

- An ultrasound of the kidneys, ureters, and bladder might be used as the initial imaging.

- It can aid in the diagnosis of anatomical reasons, such as a kidney stone, bladder infection, or renal tumor.

- It is also capable of detecting kidney cysts.

- The recommended technique for detecting renal stones and other morphological abnormalities of the kidneys is an abdominopelvic CT scan with or without contrast. If a CT scan is contraindicated or ineffective, an MRI of the abdomen and pelvis might be used.

Cystoscopy

- Cystoscopy is the next step in the examination of hematuria after ruling out UTI and having negative imaging of the kidneys and ureters to identify any abnormalities.

- It can identify urothelial cancer, bladder wall inflammation, and mucosal thickening. Urinary stone removal can also be therapeutic.

Kidney biopsy

- A kidney biopsy is a gold standard for diagnosing a glomerular etiology of hematuria. A kidney biopsy should be performed after the presence of dysmorphic RBCs and RBC casts. Because it is an intrusive test, it can result in consequences such as life-threatening hemorrhage, but this is uncommon.

- A suitable renal sample consists of 2-3 biopsy cores with a sufficient number of glomeruli. To diagnose glomerulonephritis and identify a specific kind, light microscopy, electron microscopy, and immunofluorescence are used to examine glomerulus structure.

Management of Hematuria

- Management is determined by the underlying etiology.

- Observation may be a suitable approach for asymptomatic intermittent hematuria with negative imaging, stable renal functions, and no proteinuria.

- Visible hematuria requires immediate attention. First and foremost, hemodynamic stability must be ensured.

- Blood products, transfusions, or drugs should be used to treat any hematological abnormalities.

- Interventional radiology-guided embolism is used in rare cases to halt life-threatening bleeding from the renal vasculature or to treat hemorrhagic cystitis that has not responded to standard therapy.

Non-glomerular hematuria

- A 7-14 days regimen of oral or intravenous antibiotics is used to treat acute UTIs.

- Controlling pain and giving fluids are important aspects of nephrolithiasis therapy. The size and location of kidney stones may necessitate further care.

- The majority of 0.5 cm stones pass naturally. Larger, more bothersome stones may necessitate lithotripsy or a nephrostomy.

- Nephrectomy would be required if the renal cell carcinoma was restricted to the kidneys. Metastatic cancer needs staging and further treatment. Transitional cell carcinoma needs correct staging as well as expert advice for further therapy.

Glomerular hematuria

- Some inherited disorders, such as Alport’s, thin basement membrane disease, and polycystic kidney disease, necessitate renal function monitoring and regular follow-up.

- Supportive treatment is required for post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis.

- The management of IgA nephropathy is determined by the degree of proteinuria and renal function. Creatinine levels that are relatively normal with mild proteinuria can be treated conservatively.

- High-risk characteristics, such as increasing creatinine, chronic proteinuria of 1000mg/day, and active disease on renal biopsy, are indicators that immunosuppressive medication, particularly steroids, should be considered.

Surgical management

Surgery is not the first-line management. Surgery is often only performed on patients who have either:

- Urolithiasis, particularly those with a solitary kidney, bilateral urolithiasis with blockage, infection, renal failure, hemodynamic instability, or stones that cannot pass on their own.

- BPH (which cannot be treated by medication)

- Prostate cancer

- Ureteroarterial fistulae

Complications of Hematuria

- Acute renal failure

- Severe Anemia

- Hypertension

- Electrolyte imbalance

- Seizure

- Congestive heart failure

Prognosis

- Children with isolated asymptomatic microscopic hematuria recover well in general. However, those with concomitant abnormalities (e.g., hypertension, proteinuria, abnormal serum creatinine levels) are more likely to have significant issues.

- Because hematuria is the end product of several processes, its morbidity and death rates are determined by the main mechanism that caused it.

- Hematuria in adults should be taken seriously because it may indicate cancer.

Summary

- Hematuria is the presence of RBCs in the urine, and it can be categorized based on the amount, occurrence when urinating, and source of bleeding.

- Color changes in the urine are not visible to the human eye in microhematuria, and RBCs can only be seen under a microscope.

- Macrohematuria (gross hematuria) is a noticeable darkening of urine caused by frank blood.

- Glomerular hematuria is caused by glomerular injury.

- Non-glomerular hematuria is caused by kidney or upper/lower urinary tract injury.

- If hematuria is found, patients should be evaluated further (e.g., urinalysis) to establish the underlying reason.

- Management is determined based on the underlying etiology.

References

- Davis, R., Jones, J. S., Barocas, D. A., Castle, E. P., Lang, E. K., Leveillee, R. J., Messing, E. M., Miller, S. D., Peterson, A. C., Turk, T. M.T., & Weitzel, W. (2012, Dec 1). Diagnosis, evaluation and follow-up of asymptomatic microhematuria (AMH) in adults: AUA guideline. The Journal of urology, 188(6S), 2473-2481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2012.09.078

- Massengill, S. F. (2008, Oct). Hematuria. Pediatrics in Review, 29(10), 342-348. doi: 10.1542/pir.29-10-342

- Ingelfinger, J. R. (2021, Jul 8). Hematuria in adults. New England Journal of Medicine, 385(2), 153-163. Doi:10.1056/NEJMra1604481

- Peterson, L. M., & Reed, H. S. (2019, Jun). Hematuria. Primary Care: Clinics in Office Practice, 46(2), 265-273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pop.2019.02.008

- Bolenz, C., Schröppel, B., Eisenhardt, A., Schmitz-Dräger, B. J., & Grimm, M. O. (2018, Nov). The investigation of hematuria. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International, 115(48), 801-807. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2018.0801

- Margulis, V., & Sagalowsky, A. I. (2011, Jan). Assessment of hematuria. Medical Clinics, 95(1), 153-159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2010.08.028

- Avellino, G. J., Bose, S., & Wang, D. S. (2016, Jun). Diagnosis and management of hematuria. Surgical Clinics of North America, 96(3), 503-515. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.suc.2016.02.007

- Vlasschaert, C., & Lanktree, M. B. (2020, Apr 6). Microscopic hematuria. CMAJ, 192(14), E370-E370. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.191615

- Saleem, M. O., & Hamawy, K. (2022, Jan). Hematuria. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534213/

- Gulati, S. (2020, May 10). Hematuria. Medscape. Retrieved 2023, January 25 from https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/981898-overview