Introduction

Urethritis is a lower urinary tract infection that causes inflammation of the urethra, a fibromuscular tube that excretes urine in both males and females and semen in males. Urethritis is closely linked to sexually transmitted diseases and can be gonococcal or non-gonococcal.

- Although this condition can be caused by infectious or noninfectious causes, the word urethritis is usually reserved for urethral inflammation caused by a sexually transmitted disease (STD).

- The most common findings in urethritis are dysuria, urethral discharge, and/or pruritus at the urethra’s end. The characteristic physical finding is urethral discharge.

- Despite advances in the diagnosis and management of urethritis, it continues to be a global public health issue.

- Compared to the general population, people with urethritis have a higher risk of sexual behavior.

- Including cystitis and prostatitis, urethritis is also a cause of lower urinary tract infections.

Incidence

- Every year, over 62 million new cases of gonococcal urethritis and 89 million new cases of non-gonococcal urethritis are recorded worldwide.

- Neisseria gonorrhea (N. gonorrhea) and Chlamydia trachomatis (C. trachomatis) are the most common causative organisms.

- Chlamydia: Almost two-thirds of chlamydia infections occur in young people aged 15 to 24.

- Gonorrhea: The highest incidence rates are seen in males and females aged 20 to 24 years.

- Up to 75% of females with the illness are asymptomatic or have cystitis, vaginitis, or cervicitis.

- Men who have sex with men are more likely to develop urethritis than heterosexual males or females in general.

Classification of Urethritis

Gonococcal Urethritis (GU)

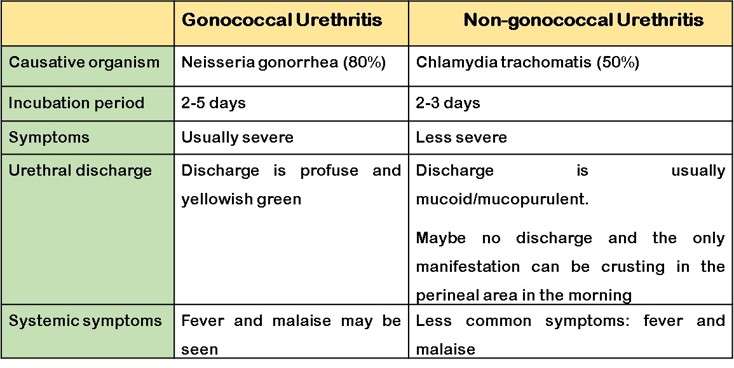

- Neisseria gonorrhoeae, a gram-negative intracellular diplococcus, causes 80% of instances of GU. It has a shorter incubation time than non-gonococcal urethritis (NGU), and the onset of dysuria and purulent discharge is sudden.

- In female patients, GU may resolve and result in the asymptomatic carriage. With adults, carriage may last for a few days to many months. In children, the duration is unclear.

- A purulent urethral discharge develops after a short incubation period of 2 to 5 days following intercourse, with discomfort when passing urine. If the infection extends to the proximal urethra, the frequency of micturition may increase.

- In contrast to females, where around 70% of gonococcal infections are asymptomatic, approximately 90% of males suffer such symptoms as a result of infection.

- Male patients with untreated GU also are at risk of developing epididymitis, prostatitis, and urethral stricture.

- Women who have asymptomatic vaginal infections may develop the pelvic inflammatory disease, which leads to tubal scarring and infertility.

- Asymptomatic gonorrheal infections can have systemic side effects like arthritis, endocarditis, and necrotic skin lesions.

Non-gonococcal Urethritis (NGU)

- NGU, or urethral inflammation, is the most prevalent sexually transmitted disease among males. NGU, which accounts for 50% of urethritis cases, has a longer incubation time than GU, and the start of dysuria or, less typically, a mucopurulent discharge is subacute.

- Patients with NGU are significantly more likely to be asymptomatic than patients with GU.

- C. trachomatis

- Ureaplasma urealyticum

- Trichomonas vaginalis

- Herpes simple virus

- Adenovirus

- Gardnerella vaginalis

- Mycoplasma genitalium

Causes of Urethritis

Infectious Etiology

- The most common cause of urethritis is N. gonorrhea. Neisseria gonorrhea is a gram-negative diplococci bacterium that passes through sexual contact. The incubation phase lasts between 2 and 5 days. Patients are often co-infected with Chlamydia trachomatis.

- C. trachomatis is the most prevalent nongonococcal cause of urethritis and is also transmitted sexually. C. trachomatis is an obligate intracellular parasitic gram-negative bacterium. In most cases, the incubation period lasts 7-14 days. It is frequently co-infected with Mycoplasma genitalium and N. gonorrhea.

- Other infectious etiologies are:

- Mycoplasma genitalium

- Trichomonas vaginalis

- Herpes Simplex virus

- Adenovirus

- Treponema pallidum

- Haemophilus influenzae

- Neisseria meningitides

- Ureaplasma urealyticum

- Candida

Non-infectious Etiology

Genital irritation:

- Rubbing or pressure from intercourse, tight clothes, or other factors.

- Engaging in physical exercises, such as riding a bicycle.

- Irritants such as different body powders, soaps, and spermicides.

- Thin and dry tissues of the urethra and bladder and low estrogen levels during menopause.

Trauma

- The less prevalent cause of urethritis is trauma. However, intermittent catheterization, urethral instrumentation, or the insertion of a foreign substance can all cause inflammation and discomfort.

Other causes

- Urethral stricure

- Dehydration

Pathophysiology of Urethritis

Gonococcal urethritis

- N. gonorrhea infection typically affects the urethra in males and the vagina in females. Nevertheless, rectal and pharyngeal carriage can occasionally happen in the absence of urethral colonization.

- The development of extracellular proteases that cleave IgA, pili, and the capacity to adhere to urethral epithelial cells are examples of gonococcal virulence factors.

- Pili, which are filamentous outer membrane appendages made up of many subunits, the most significant of which is pilin, facilitate the first attachment of gonococci to the surface of columnar epithelial cells.

- At the level of the mucosal cells, numerous adhesins engage with host receptors to cause local invasion. When gonococci adhere, a process known as membrane ruffling causes the bacteria to internalize.

Non-gonococcal Urethritis

- Chlamydia is an obligate intracellular parasite that is a structurally complex organism that contains DNA and RNA.

- The initial stage in the susceptible host cell’s infectious process is attachment.

- It is followed by phagocytosis, which may be partially mediated by macromolecules in the chlamydial cell membrane, and subsequently the inability of cellular lysosomes to merge with the phagosome containing the elementary body.

- The elementary bodies undergo physiologic modifications following these two important occurrences, and after around 72 hours, they are liberated from the host cell as new infective elementary organisms.

Other Mechanisms

- In younger children, particularly in girls, urethritis may also be brought on by the entry of fecal bacteria or pinworms into the urethra during the early stages of toilet training.

- Bubble baths and other chemical and physical irritants may be linked to inflammation.

- Idiopathic urethritis is another condition that causes hematuria and dysuria in young boys and girls.

- Common histopathologic signs of urethritis include edema of the mucosa, red blood cell presence, inflammation, dysuria, hematuria, and microscopic pyuria.

Signs and Symptoms of Urethritis

- N. gonorrhea can be asymptomatic or frequently accompanied by profuse, purulent, or mucopurulent urethral discharge in males.

- Urethritis in women frequently coexists with cervicitis or may not even present with any symptoms. The most frequent symptom, if any, is dysuria. Women may also experience urgency and frequency.

In female

- Abnormal vaginal discharge

- Abdominal and pelvic pain

- Urge to urinate repeatedly

- Itching and tenderness in the vaginal area

- Sexual intercourse may be painful.

- Gastrointestinal discomfort

- Mild headaches, low fever, and chills

- Symptoms during menstruation can get worse.

In male

- Hematuria and blood in semen

- Pain during ejaculation

- Burning micturition

- Swollen lymph nodes around the groin

- Itching and redness in the penis

- Orchialgia- Chronic testicular pain.

Difference between Gonococcal and Non-gonococcal Urethritis

Diagnosis of Urethritis

Medical history

- Symptoms such as pruritus, discharge, or dysuria.

Physical examination

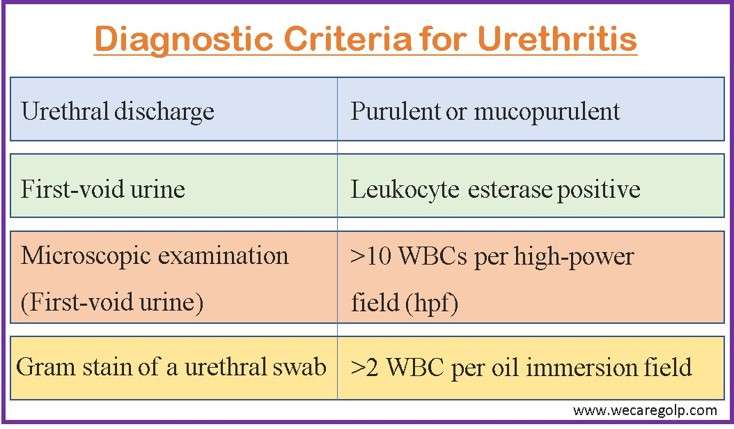

- Discharge from the urethra (mucopurulent or purulent)

- Enlarged lymph nodes and tenderness of the urethra

- Tenderness of the lower abdomen

Urinalysis

- Positive leukocyte esterase and >10 WBCs per high-power field (hpf) of the first-void urine on microscopic examination,

Gram-stain

- Urethral fluid is collected on a cotton swab and examined under the microscope for the presence of bacteria. The shape, size, and color of the cells help identify the type of infection-causing bacteria.

- Diagnosis can be done with >2 WBC per oil immersion field from Gram-stain of urethral secretion.

- NGU is consistent with polymorphonuclear neutrophils present but no visible organisms.

- Gram-stain evidence showing the presence of WBC-carrying intracellular purple diplococci establishes the presence of presumed gonococcal infection.

Nucleic Acid Amplification Tests (NAAT)

- These tests are more specific and more sensitive than cultures.

- The preferred test for identifying C. trachomatis, N. gonorrhea, and Mycoplasma genitalium is now NAATs rather than culture.

- Furthermore, if there is a high clinical suspicion of urethritis and the diagnostic criteria have not been met, nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) are advised.

Management of Urethritis

The cornerstone therapy for urethritis is dual antibiotic therapy. Both GU and NGU should receive antibiotic treatment. Post gonococcal urethritis risk is about 50% if concurrent therapy for NGU is not given.

Gonococcal Urethritis

- A single dose of ceftriaxone 500 mg intramuscular injection is the recommended course of therapy.

- Treatment with doxycycline 100 mg twice a day for 7 days is added if chlamydia has not been ruled out.

- The same treatment is used for Neisseria meningitides urethritis.

Non-gonococcal Urethritis

- The preferred course of therapy is a single dose of oral azithromycin (1 g) or 100 mg of doxycycline twice a day for seven days.

- Ofloxacin 300 mg twice a day for seven days or levofloxacin 500 mg once daily for seven days are two alternative treatments.

- If gonorrhea is also present, therapy should include a single 500 mg intramuscular dosage of ceftriaxone in addition to a 1-gram oral dose of azithromycin.

- The recommended dosage of azithromycin for pregnant women is 1 gram per oral.

Recurrent or Persistent Urethritis

Before considering further antimicrobial medication, an objective diagnosis of persistent or recurrent NGU should be made. Therapy failure or reinfection after effective treatment might result in symptomatic recurrent or persistent urethritis. The usefulness of prolonging the duration of antimicrobials in men who have persisting symptoms after therapy but no objective indications of urethral inflammation has not been shown.

- Metronidazole 2 gm PO (Single dose) or Tinidazole 2 gm PO (Single dose) plus Azithromycin 1gm PO (Single dose).

- Levofloxacin, ofloxacin, erythromycin estolate, and doxycycline are not recommended to be used by female patients who are pregnant or breastfeeding.

- Three months after receiving treatment, all patients should have their tests redone, and anyone who becomes reinfected should start taking azithromycin.

- It is appropriate to advise patients to stop using spermicides, use fragrance-free soaps, lubricants, and other items, drink more water, and avoid carbonated beverages, reduce penile trauma through less frequent/ vigorous sexual activity or masturbation.

- Men with urethritis brought on by a STI should be encouraged to refrain from sex for a week after treatment begins. Patient education should focus on raising knowledge of and lowering STI risk factors.

- All sex partners of men who have had NGU in the last 60 days should be referred for examination and testing, as well as presumptive therapy with a disease drug regimen.

- All partners should be assessed and treated by the treatment section for their specific pathogen; if a partner is unable to get timely care, Expedited Partner Therapy (EPT) might be an alternative strategy.

- To avoid reinfection, sex partners should avoid sexual contact until they and their partners have been treated.

Complications

Urethritis complications can be categorized according to causative organisms which are:

| Neisseria gonorrhea | Chlamydia trachomatis |

| Penile Edema | Pelvic Inflammatory Disease |

| Periurethral Abscesses, | Infertility |

| Post-Inflammatory Urethral Strictures | Ectopic Pregnancy |

| Penile Lymphangitis | Fitz-Hugh-Curtis Syndrome |

| Proctitis | |

| Reactive Arthritis |

Prevention

- Since the most prevalent cause of urethritis is an infectious condition, reducing STD transmission is one of the most effective urethritis prevention tactics.

- The best strategy to prevent STD transmission is to either refrain from oral, anal, or vaginal sex as well as to be in a long-term, monogamous relationship with a partner who is STD-free. When worn regularly and appropriately, male condoms lower the risk of chlamydial infection, gonorrhea, and trichomoniasis transmission.

- The evidence for cervical diaphragms, topical microbicides, and spermicides as STD prevention methods is scant to nonexistent.

- Hysterectomy, non-barrier contraception, and surgical sterilization do not give STD prevention.

- Avoid urethral irritants such as fragrant soaps, body washes, lotions, or lubricants as well as frequent masturbation and sexual activity in people with noninfectious urethritis.

- It is crucial to inform the patient about safe sexual behavior if a STI has been identified. This involves talking with the patient about telling their partner(s) and encouraging them to get checked out by a medical expert and seek the right kind of care.

- It is important to emphasize the possibility of recurrence even in asymptomatic partners since they can have hidden the condition.

- Patients should be advised to delay having a relationship until both they and their partner(s) have received effective treatment and are symptom-free.

Prognosis

- When identified and treated properly, patients have a great prognosis and a high percentage of the recovery.

- When an accurate diagnosis is done and given the nature of the infectious organism, treatment for sexual partners should be addressed.

- Unfortunately, untreated partners frequently re-infect sexually active people. It is crucial to look at co-infections and other less frequent causal agents when urethritis persists despite therapy for the most prevalent organisms.

- As some of the causal organisms do pose the danger of unpleasant and harmful sequelae, quick diagnosis and treatment is crucial.

Summary

- Urethritis is an inflammation of the urethra that can be caused by both infectious and noninfectious mechanisms. There are two types of urethritis: gonococcal and nongonococcal.

- Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis are common causative organisms of urethritis.

- Urethritis is usually asymptomatic; if it occurs, the symptoms differ depending on the causative organism. The symptoms of urethritis are dysuria, pruritus, burning, and discharge at the urethral meatus. Gonorrhea as the causal organism is suggested by the odorous purulent discharge. Dysuria is a frequent symptom of Chlamydia.

- Evidence of discharge, WBCs count on urine, urethral swab, and Gram-stain are the diagnostic tests for urethritis

- Urethritis symptoms usually resolve on their own over time, regardless of therapy. Antibiotics should be used to avoid morbidity and infection spread to others. Recent sexual contacts (those who had sexual contact with the patient within 60 days of symptom start) are also treated to avoid reinfection of the index patient.

References

- Young, A., Toncar, A., & Wray, A. A. (2021). Urethritis. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537282/

- Holmes, K. K., Handsfield, H. H., Wang, S. P., Wentworth, B. B., Turck, M., Anderson, J. B., & Alexander, E. R. (1975). Etiology of nongonococcal urethritis. New England journal of medicine, 292(23), 1199-1205. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197506052922301

- Swartz, S. L., Kraus, S. J., Herrmann, K. L., Stargel, M. D., Brown, W. J., & Allen, S. D. (1978). Diagnosis and etiology of nongonococcal urethritis. Journal of Infectious Diseases, 138(4), 445-454. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/138.4.445

- Bachmann, L. H., Manhart, L. E., Martin, D. H., Seña, A. C., Dimitrakoff, J., Jensen, J. S., & Gaydos, C. A. (2015). Advances in the understanding and treatment of male urethritis. Clinical infectious diseases, 61(suppl_8), 763-769. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/civ755

- Sarier, M., & Kukul, E. (2019). Classification of non-gonococcal urethritis: a review. International urology and nephrology, 51(6), 901-907. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11255-019-02140-2

- Bartoletti, R., Wagenlehner, F. M., Johansen, T. E. B., Köves, B., Cai, T., Tandogdu, Z., & Bonkat, G. (2019). Management of urethritis: Is it still the time for empirical antibiotic treatments?. European Urology Focus, 5(1), 29-35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euf.2018.10.006

- Meesaeng, M., Sakboonyarat, B., & Thaiwat, S. (2021). Incidence and risk factors of gonococcal urethritis reinfection among Thai male patients in a multicenter, retrospective cohort study. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 1-7. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-021-02398-6

- Irimie, M. (2020). Risk Factors and Aetiological Agents of Urethritis in Men with Urethritis in Brașov County. Bulletin of the Transilvania University of Brasov. Series VI: Medical Sciences, 13/62), 37-42. https://doi.org/10.31926/but.ms.2020.62.13.2.5

- Whitaker, DL. (2022, October 3). Urethritis. Medscape. Retrieved 2023, Jan 14 from https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/438091-overview