Introduction

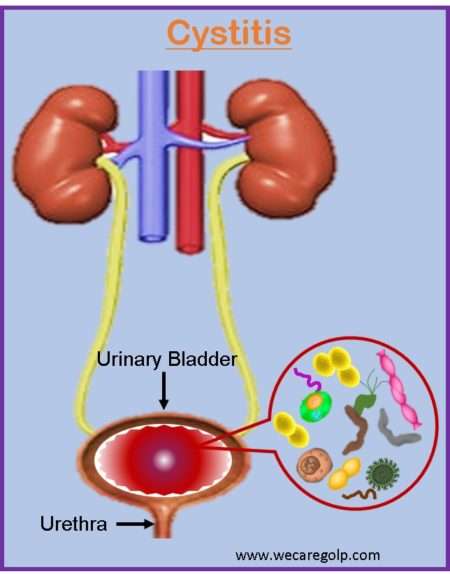

Cystitis refers to a group of disorders with different etiologies and pathologic processes but similar clinical manifestations. The most common symptoms are dysuria, frequency, urgency, and, on rare occasions, suprapubic discomfort.

- The symptoms, however, are generic and may be caused by infection of the lower genitourinary tract (urethra, vagina) or by noninfectious diseases such as bladder cancer, urethral diverticulum, and calculi.

- When bacteria from the vaginal or fecal flora colonize the periurethral mucosa and ascend to the urinary bladder, it frequently results in cystitis.

- It is characterized as a lower urinary tract infection (UTI) when caused by an infection. It is primarily caused by ascending infections of the urethra. Although, it can also be caused by descending infections of the blood or lymphatic system.

- The illness primarily affects women; however, it can affect either gender and people of all ages.

Incidence

- Urinary tract infections are more common in women than in men.

- More than 30% of women are expected to have at least one episode of cystitis.

- It affects women more than men. The male-to-female ratio is four to one.

- Acute uncomplicated cystitis most usually affects women between the ages of 18 and 39.

- There is no racial disparity in cystitis.

- It is expected that one-third of all women can get it at some point in their lives. Many of these patients will develop recurrent cystitis.

Classification of Cystitis

According to Etiology

There are many medically distinct forms of cystitis, each with a different etiology and treatment strategy:

Traumatic cystitis

- Presumably, the most prevalent kind of cystitis in females is traumatic cystitis. It is induced by bruising of the bladder, often during very forceful sexual activity.

- This is typically followed by bacterial cystitis, which frequently results from coliform bacteria entering the bladder through the urethra from the bowel. Intercourse and lack of circumcision are significant risk factors for traumatic cystitis.

Hemorrhagic cystitis

- Hemorrhagic cystitis is characterized by lower urinary tract symptoms such as hematuria and irritative voiding. It happens when chemicals, infections, radiation, medications, or diseases harm the transitional epithelium and blood vessels of the bladder.

- Bacteria and viruses are among the infectious causes of hemorrhagic cystitis. Most frequently, non-infectious hemorrhagic cystitis affects individuals who have had pelvic radiation therapy (see the illustration below), chemotherapy, or a combination of the two.

- Patients who are affected may have microscopic hematuria that is asymptomatic or extensive hematuria with clots that causes urine retention. The origin, level of bleeding, and symptoms all influence treatment.

Interstitial cystitis

- Interstitial cystitis, also known as bladder pain syndrome (IC/PBS), is described as a bladder injury that causes persistent discomfort and is seldom associated with infection.

- Urinary frequency, urgency, and pelvic discomfort are clinical symptoms that can occur both during the day and at night. There is no known cause or pathophysiology for interstitial cystitis, and there are no established diagnostic standards for the condition.

- Despite extensive study, there are no universally successful therapies; instead, therapy often involves a combination of supportive, behavioral, and pharmacological interventions. Rarely, surgical intervention is necessary.

- In the absence of infection or other identified causes, the American Urological Association (AUA) defines IC/BPS as an unpleasant feeling (pain, pressure, discomfort) considered to be connected to the urinary bladder, accompanied with lower urinary tract symptoms lasting more than six weeks.

- In the absence of a confirmed urinary infection or other obvious pathology, the International Continence Society has defined the term PBS as suprapubic pain with bladder filling and increased daytime and nighttime frequency. The diagnosis is only given to patients who have the defining cystoscopic and histologic features of the condition.

Eosinophilic cystitis

- Eosinophilic cystitis (EC) is an uncommon clinicopathological disorder defined by transmural inflammation of the bladder mostly with eosinophils, with or without muscle necrosis. This inflammation is distinguished by eosinophilic infiltration of the bladder wall.

- The majority of EC patients appear with urinary bladder mucosal lesions. In children, EC may be caused by infection with Schistosoma hematobium or certain drugs. Some consider it a form of interstitial cystitis.

Papillary-polypoid cystitis

- Polypoid and papillary cystitis is a non-specific mucosal response caused by a persistently irritated bladder that manifests as polypoid or papillary lesions.

- It is prevalent and gets worse with repeated catheterization, but it is not always caused by bladder catheterization.

- On imaging, it occasionally appears as a mass that resembles other papillary urothelial neoplasms and is mistaken as bladder cancer.

Radiation cystitis

- It is the inflammation and subsequent cellular death of the bladder that happens as a side effect of cancer therapy radiation.

- It typically develops after pelvic radiation, which may be necessary for the treatment of primary bladder cancer or cancers in the bladder, colon, rectum, ovaries, uterus, and prostate.

- Radiation damage can be acute, happening less than six months after radiation therapy, or delayed, occurring longer than six months after radiation therapy.

Xanthogranulomatous cystitis

- Xanthogranulomatous cystitis (XC) is a rare, benign, chronic inflammatory bladder condition. Xanthoma cells (lipid-laden macrophages), multinucleated giant cells, cholesterol clefts, fibrosis, and calcification are pathological features of XC.

- It has been found in a variety of locations, including the kidney, gallbladder, colon, appendix, ovary, pancreas, salivary glands, and endometrium. However, it is exceedingly uncommon in the bladder and is frequently misdiagnosed.

Follicular cystitis

- Follicular cystitis (FC) is an uncommon and non-specific inflammatory bladder illness that mostly affects women and is distinguished by the presence of lymphoid follicles in the bladder wall’s lamina propria.

- A detailed histopathologic evaluation is required to make the diagnosis, which requires the detection of distinctive follicles in the bladder wall lamina propria, which are conventionally defined as lymphoid follicles having germinal centers with lymphocytic collars.

- It has an unknown origin and pathophysiology, and the prognosis is uncertain.

Cystitis cystica

- It is a frequent benign urinary bladder disorder characterized by a reactive inflammatory alteration of the bladder mucosa, the production of subepithelial vesicles or cysts, and glandular metaplasia (cystitis glandularis).

- Von Brunn’s nests are invaginations of hyperplastic urothelial extensions into the superficial lamina propria.

- These inflammatory projections are considered reactive but not cancerous. It occurs when the urothelial cells in von Brunn’s nest lumens degenerate, resulting in cystic alterations.

- Further metaplasia leads to cystitis glandularis, which can occasionally proceed to vesical adenocarcinoma.

- Cystitis cystica and cystitis glandularis are most commonly caused by prolonged irritation or inflammation.

- They are often asymptomatic but may present with non-specific signs and symptoms that need careful examination to rule out other morphologically similar malignant tumors, such as bladder adenocarcinoma.

Emphysematous cystitis

- Emphysematous cystitis (EC) is an uncommon kind of complex urinary tract infection distinguished by the presence of gas inside the bladder wall and lumen. Patients with EC have a wide range of clinical symptoms, from asymptomatic to severe sepsis.

- EC is most commonly seen in older women with type 2 diabetes. Urine cultures are frequently used to isolate Escherichia coli (E. coli) and Klebsiella pneumoniae.

- Plain conventional abdominal radiography and computed tomography are critical for making a definite diagnosis of EC. Most instances are treatable with antibiotics, bladder drainage, and glycemic management.

- With a mortality incidence of 7%, EC is potentially fatal. Early medical care can help to improve the prognosis without requiring surgical surgery.

According to Duration and Treatment

Acute uncomplicated cystitis

- The majority of urinary tract infections are simple cystitis. Acute uncomplicated cystitis is distinguished by frequency and dysuria in an immunocompetent woman of reproductive age with no comorbidities or urologic abnormalities.

- It is an infection that is limited to the lower urinary tract and is most usually encountered in women with normal genitourinary anatomy and function, as well as children over the age of two.

- Men’s acute urinary infections are always treated as complex infections.

- Patients with acute uncomplicated cystitis can be treated with a single antibiotic dosage or a three-day course.

- Patients have a normal, unobstructed genitourinary tract, no history of recent instrumentation, and symptoms confined to the lower urinary tract.

- Cystitis without complications is most common in young, sexually active women. Patients frequently complain of dysuria, urine frequency, urgency, and/or suprapubic discomfort.

Complicated cystitis

- It is linked to an underlying illness that raises the likelihood of therapy failure. Diabetes, symptoms for 7 days or more before seeking therapy, renal failure, functional or anatomic abnormalities of the urinary system, renal transplantation, an indwelling catheter stent, or immunosuppression are examples of underlying disorders.

- In persons with functional or structural abnormalities, complicated urinary tract infections occur regardless of age or gender. In elderly men, urinary tract infection is always regarded as complicated.

- People with complex cystitis often require more treatment than patients with simple cystitis.

Recurrent/chronic cystitis

- Recurrent cystitis is typically defined as three occurrences of UTI in the past 12 months or two bouts in the previous six months.

- Recurrent UTIs are extremely uncomfortable for women and have a significant influence on ambulatory health care expenses due to outpatient visits, diagnostic testing, and medicines.

- Long-term inflammation and infection can cause bladder hyperreflexia and altered sensations, often known as allodynia.

- Patients with recurrent cystitis may require 6-12 months of preventive antibiotic medication.

According to the Causative Organism

Bacteria

- E. coli

- Enterococcus faecalis

- Proteus mirabilis

- Klebsiella

- Staphylococcus saprophyticus

- Staphylococcus aureus

- Lactobacillus

- Group B Streptococci

- Pseudomonas

Fungi

- Candida

Virus

- HIV

- Adenovirus

- Cytomegalovirus

- Polyomaviruses

Parasite

- Toxoplasma Gondii

Causes of Cystitis

The most frequent causes of cystitis are Escherichia coli, Proteus, Klebsiella, and Enterobacter.

- Gram-negative bacteria

- E. coli

- Klebsiella

- Enterobacter

- Proteus species

- Gram-positive bacteria

- Enterococci

- Staphylococcus saprophyticus

- Women are more likely to develop cystitis as a result of their short urethra

- Renal tuberculosis almost always precedes tuberculous cystitis.

Predisposing Factors of Cystitis

- Bladder calculi

- Urinary Obstruction

- Instrumentation

- Immune deficiency

- Radiation therapy

- Cytotoxic antitumor drugs, such as cyclophosphamide, may develop hemorrhagic cystitis

- Recent sexual intercourse (may introduce bacteria in the urethra)

- Use of a diaphragm with spermicide

- Post-menopausal status (loss of protective vaginal flora due to low estrogen)

- Homosexual men

- Genetic predisposition or family history

- Lack of circumcision

- Old age

- Immobility

- Any blockage of the bladder or urethra

- Diabetes Mellitus (hyperglycemia inhibits neutrophil migration and phagocytosis)

- Benign prostatic hypertrophy

- Fecal incontinence

- Pregnancy

- Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

- Urinary retention

Signs and Symptoms of Cystitis

A triad of symptoms is present in all kinds of cystitis.

- Urinary frequency: In acute cases, the patient needs to urinate every 15-20 minutes.

- Pain: Lower abdominal pain is localized over the bladder region or in the suprapubic region

- Dysuria

Other symptoms

- Nocturia

- Urgency

- Low volume voids

- Hematuria

- Cloudy urine, Foul odor

- Painful sexual intercourse

- Systemic signs of inflammation like high temperature, chills, and general malaise.

In infants

- Decreased feeding

- Fever

- Excessive crying

- Fussiness

- Insomnia

In elderly

- Incontinence

- Fatigue

- Dementia in some case

Pathophysiology of Cystitis

- Cystitis typically arises as a result of bacteria from the vaginal or fecal flora colonizing the periurethral mucosa and ascending to the urinary bladder.

- Microbial virulence factors in uropathogens may enable them to bypass host defenses and infect tissues in the urinary system.

- Due to their longer physical urethra, drier periurethral environment, and prostatic fluid’s antibacterial defenses, men are far less likely to get UTIs.

- The pathogenesis of complex UTIs is primarily governed by the underlying host variables.

- Patients with diabetes may be more prone to developing UTIs due to immune system impairment and voiding dysfunction brought on by autonomic neuropathy.

- In renal insufficiency, uremic toxin buildup may weaken host defenses, and reduced renal blood flow may impede the clearance of antimicrobials.

- Renal stones can restrict the flow of urine and create an infection risk nidus. Pathogens may remain in retained urine pools in the urinary bladder during urinary catheterization, and internal and exterior biofilms may grow on the catheter.

Diagnosis of Cystitis

When a patient exhibits the classic signs and symptoms (dysuria, frequent or urgent urination, and/or suprapubic discomfort), a clinical diagnosis is made.

Urinalysis

A urinary tract infection may be present if nitrites, leukocyte esterase, or bacteria-containing WBCs are present on a microscopic examination or a dipstick.

- White blood cells (WBCs) or red blood cells are frequently seen in urine results (RBCs).

- 5–10 WBC/hpf or 27 WBC/microliter in pyuria

- Dipstick:

- The nitrate reductase test is used to distinguish between bacteria based on their capacity or incapacity to employ anaerobic respiration to convert nitrate (NO3) to nitrite (NO2).

- A urine test called leukocyte esterase can detect white blood cells and other abnormalities linked to cystitis.

Urine Culture

- Finding the etiologic microorganisms and figuring out the antibiotic susceptibility profiles benefit from a urine culture.

- Larger than or equal to 100,000 CFU (colony forming units)/mL suggests clinically relevant bacteriuria, although in males and samples taken after direct bladder catheterization, a growth of greater than or equal to 1,000 CFU is regarded as important.

- A urinary tract infection is not ruled out by a CFU count of less than 100,000/mL.

- Urine cultures are frequently viewed as unnecessary and not routinely performed in cases of acute, uncomplicated cystitis, even though patients with persistent symptoms and presumed treatment failures can benefit greatly from them, especially given the rising rates of antibiotic resistance.

Men who experience cystitis flare-ups frequently should get tested for prostatitis.

Imaging Studies

Patients with complicated cystitis who do not improve after receiving the proper antimicrobial therapy for 48 to 72 hours may need to undergo further testing that involves radiographic imaging of the upper urinary tract.

- The recommended test is often a CT scan since it is more sensitive to aberrant processes such as diverticula, abscess development, urinary blockage, and stone formation that may interfere with therapy response.

- In individuals who should limit radiation exposure or otherwise avoid CT imaging, ultrasound of the kidneys, particularly when paired with a KUB (short for kidneys, ureters, and bladder: i.e., a flat plate of the abdomen), may be sufficient.

- Additionally, a cystoscopy is an optional procedure.

Management of Cystitis

Antimicrobial Treatment

Treatment for Uncomplicated Cystitis

Antibiotic treatment is used to treat acute uncomplicated cystitis. Based on a patient’s risk factors for infection with various drug-resistant organisms, an antimicrobial agent is chosen. One of the first-line or recommended antimicrobial medicines is administered to patients who have a low probability of developing resistant pathogenic organisms, including:

- Nitrofurantoin 100 mg twice a day for 5 to 7 days

- Double-strength Sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim (SMX-TMP) twice daily for three days (if local antibiotic resistance is less than 20%)

- Fosfomycin 3 gm as a single oral dose

Treatment for Complicated Cystitis

Patients with complicated cystitis typically need more therapy time than those with uncomplicated cystitis.

Empiric therapy for complicated cystitis

- Recommended regimen Ofloxacin 200–400 mg pre-oral (PO) bid.

- Recommended regimen Ciprofloxacin 250 mg bid PO or Cipro XR 500 mg q24h

- Recommended regimen Levofloxacin 250–750 mg PO q24.

Cystitis in men without prostatitis

Any male instance of cystitis is regarded as complicated. If a man has cystitis but no symptoms or indications of prostatitis, he can be treated with one of the suggested regimens listed below:

- Trimethoprim/Sulfamethoxazole 160 mg/800 mg (Bactrim DS, Septra DS) 1 tablet PO BID for 7 days (use when bacterial resistance is < 20% and the patient has no allergy)

- Ciprofloxacin (Cipro) 500 mg PO BID for 7 days or

- Ciprofloxacin extended-release (Cipro XR) 1000 mg PO once daily for 7 days or

- Levofloxacin 750 mg PO once daily for 7 days

Treatment of Cystitis for Children, Pregnant, and Nursing Women

- When giving antimicrobial agents to children or pregnant or nursing women, more care must be used in the antimicrobial therapy selection. Fluoroquinolones, Sulfonamide, Trimethoprim, and Nitrofurantoin should not be used during pregnancy.

- An effective choice for treatment in pregnant individuals is a single dosage of Fosfomycin.

- It is not well documented how long treatment should last to treat complicated cystitis patients. For 7 to 14 days, the majority of clinical trials assessed the effectiveness of antimicrobial medicines (range: 5-20 days).

- Infected patients who have had indwelling catheters for longer than two weeks should have the catheter changed, and a urine sample should be taken from the new catheter to increase the treatment’s effectiveness and reduce side effects.

- TMP-SMX DS 1 tab bid for three days

Recurrent Cystitis

- For 6–12 months, patients with recurrent cystitis may need to get preventive antibiotic treatment.

- Recurrent cystitis can be treated with the same antimicrobial medicines as are recommended for uncomplicated cystitis.

- A different first-line medication should be used to treat a recurrence of infection if it occurs within 6 months following effective treatment.

- Patients with recurrent, interstitial, and hemorrhagic cystitis are thought to benefit from hyaluronic acid.

Surgical Treatment

Cystitis surgery is often not advised. It may be taken into account in the following situations:

- Neuromodulation, transurethral surgery, bladder enlargement, and urinary diversion with or without cystectomy are surgical options for interstitial cystitis.

- Bladder tumor (Transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT))

- Mass-forming eosinophilic cystitis

- Cystitis cystica

Complications

- Pyelonephritis

- Renal or perinephric abscess formation

- Renal vein thrombosis

- Sepsis

- Acute renal failure

- Emphysematous pyelonephritis

- Prostatitis

Prevention of Cystitis

- The flow of urine and urethral flushing are encouraged by consuming enough fluids, which can help avoid recurring episodes of infection. This strategy is justified by the fact that consuming more fluids leads to an increase in voiding frequency, which dilutes and flushes germs from the urothelium.

- As a result, increasing fluid intake raises voiding frequency and volume and may lower the chance of developing recurrent cystitis.

- The majority of non-pharmacologic antimicrobial-sparing methods for preventing recurrent cystitis in premenopausal women involve educating them about risk factors including sex activity and the use of spermicidal devices.

- Lifestyle changes are frequently advised, such as urinating frequently (particularly after sexual activity), cleansing the vulvovaginal region correctly, and drinking lots of water.

- Postcoital or continuous antibiotic use is one of the preventative regimens for women who experience frequent recurrent UTIs. Self-initiated antibiotic treatment may be advantageous for women who experience fewer than three UTIs annually.

- Use of topical estrogen among postmenopausal women

- Urinary tract infections that reoccur may need anatomical assessment of structural and functional abnormalities.

- For many women, improving personal cleanliness seems to be beneficial. The following are recommendations for proper hygiene:

- Before wiping after voiding, wash your hands.

- Instead of using regular toilet paper, use adult or baby wipes.

- After voiding, wipe only once, front to back.

- Showers are preferable than baths.

- To clean the vaginal region, use a non-toxic liquid soap that has few chemicals or fragrances. Most liquid soaps and shampoos that are safe for infants are likely appropriate.

- To prevent contamination or the spread of bacteria to this crucial location, wash the vaginal first.

Prognosis

- After starting antibiotic medication, patients with uncomplicated cystitis often experience an improvement in symptoms three days later.

- Within six months of their initial UTI, 25% of women get recurrent cystitis, and the likelihood rises for those who have had more than one UTI in the past.

- In particular, complications are uncommon in individuals who receive the proper care. It is rare for uncomplicated cystitis to result in bacteremia and sepsis.

- A rare but significant side effect of a lower urinary tract infection is emphysematous cystitis. If not treated appropriately, it can be fatal and is linked to gas buildup in the bladder wall.

- Emphysematous cystitis is more likely to cause abdominal pain (80%) compared to simple cystitis (50%); pneumaturia will likely be present in about 70% of patients, and half will have bacteremia.

Summary

- Cystitis refers to a group of disorders with different etiologies and pathologic processes but similar clinical manifestations. The most common symptoms are dysuria, frequency, urgency, and, on rare occasions, suprapubic discomfort.

- According to the origin and treatment method, cystitis can be divided into several subtypes, including traumatic, interstitial, eosinophilic, hemorrhagic, foreign body, emphysematous, and cystitis cystica. Depending on how long the infection has been present, cystitis can also be categorized as either acute or chronic.

- The most typical cause of cystitis is an infection. Escherichia coli (E. Coli), a bacteria found in the lower gastrointestinal tract, is responsible for more than 80% of instances of cystitis.

- Cystitis can cause painful urination, cloudy urine, blood in the urine, frequent urination or an urgent desire to urinate, pressure in the lower pelvis, and atypical urine color.

- Pyuria, the presence of either white blood cells (WBCs) or red blood cells (RBCs) on urinalysis, and positive urine culture are laboratory results that are compatible with the diagnosis of cystitis.

- Cystitis requires antimicrobial treatment. The course of the illness (acute uncomplicated vs. complicated) and the prevalence of community resistance affect how cystitis is treated.

References

- Li, R., & Leslie, S. W. (2022, Nov 28). Cystitis. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482435/#article-20220.s7

- Hooton, T. M., & Gupta, K. (2022, Nov). Acute simple cystitis in females. UpToDate. . https://www.medilib.ir/uptodate/show/8063

- Soler, G. (2016). Cystitis and its management. Journal of the Malta College of Pharmacy Practice. 22, 21-26. https://www.um.edu.mt/library/oar/bitstream/123456789/14278/1/2016-22-4.pdf

- Patiola, S. S. (2021, Mar 8). Cystitis Empiric Therapy. Medscape. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1976451-overview

- Palazzi, D. L., Campbell, J. R. (2022, Nov). Acute infectious cystitis: Clinical features and diagnosis in children older than two years and adolescents. UpToDate. https://www.medilib.ir/uptodate/show/6012

- Colgan, R., & Williams, M. (2011). Diagnosis and treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis. American family physician, 84(7), 771-776. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2011/1001/p771.html

- Gupta, K., Hooton, T. M., Naber, K. G., Wullt, B., Colgan, R., Miller, L. G., Moran, G. J., Nicolle, L. E., Raz, R., Schaeffer, A. J., Soper, D. E. (2011, Mar 1). International clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis in women: a 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. Clinical infectious diseases, 52(5), e103-e120. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciq257

- Nicolle, L. E. (2008, Feb). Uncomplicated urinary tract infection in adults including uncomplicated pyelonephritis. Urologic Clinics of North America, 35(1), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ucl.2007.09.004

- Kolman, K. B. (2019, June). Cystitis and pyelonephritis: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. Primary Care: Clinics in Office Practice, 46(2), 191-202. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2019.01.001

- Roberts, J. A. (1996). Pathophysiology of bacterial cystitis. Advances in Bladder Research, 325-338. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-1-4615-4737-2_25