Introduction

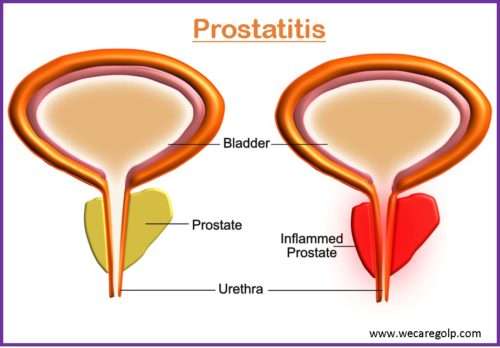

Prostatitis is an infection or inflammation of the prostate gland that manifests as several syndromes with variable clinical characteristics. Prostatitis is described as microscopic inflammation of the prostate gland tissue and is a diagnosis that encompasses a wide variety of clinical disorders.

- It is defined as painful inflammation of the prostate that is frequently associated with lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) such as urinary burning, hesitancy, and frequency, as well as sexual dysfunction or discomforts such as erectile dysfunction, painful ejaculation, and postcoital pelvic discomfort. Approximately half of the men with prostatitis experience adverse sexual effects.

- The inflammatory process might be infectious or inflammatory. Lymphocytic infiltration in the stroma directly next to the prostatic acini is the most typical histologic pattern.

- Including cystitis and urethritis, prostatitis is also a cause of lower urinary tract infections.

Epidemiology

- Prostatitis is the third most frequently diagnosed urinary condition in men over 50 after benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and prostate cancer.

- Prostatitis is the most common problem associated with the urinary tract in men younger than 50.

- There are approximately 2 million doctor visits related to prostatitis.

- The most prevalent type of prostatitis, chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome, affects 15% of men at some point in their lives.

- In comparison, the prevalence rate of prostatitis is higher than diabetes and ischemic heart disease.

- The risk of prostate cancer, LUTS, and BPH is also high with prostatitis.

Classification

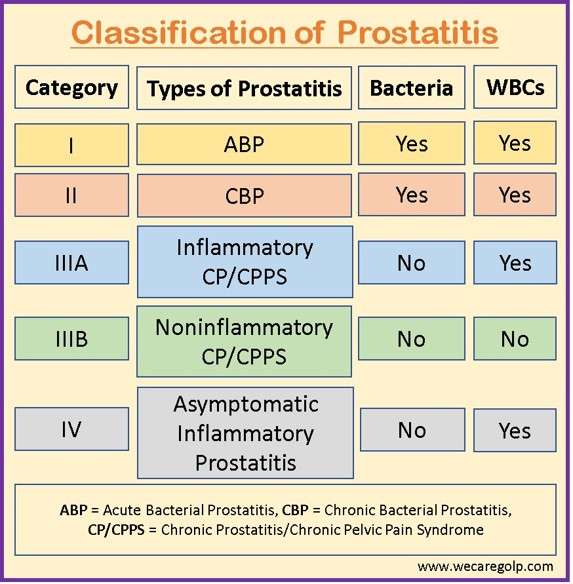

The International Prostatitis Collaborative Network and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) have developed a prostatitis classification system.

- Category I: Acute bacterial prostatitis

- Category II: Chronic bacterial prostatitis

- Category III: Chronic abacterial prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome, which is subdivided into IIIA (inflammatory) and IIIB (noninflammatory) disease

- Category IV: Asymptomatic inflammatory prostatitis (histologic or andrological diagnosis)

Category I: Acute bacterial prostatitis

- Acute bacterial prostatitis (ABP) is an infection of the prostate gland that produces pelvic discomfort and urinary tract symptoms including

- Dysuria

- Urine frequency

- Urinary retention

- Systemic symptoms like fever, chills, nausea, emesis, and malaise.

- ABP accounts for around 5% of prostatitis cases. Although uncommon, ABP requires rapid diagnosis and treatment since it can lead to sepsis.

- It is caused by the proliferation of bacteria within the prostate gland as a result of intraprostatic reflux of urine-containing organisms such as Escherichia coli, Enterococcus, and Proteus species.

Category II: Chronic bacterial prostatitis

- Chronic bacterial prostatitis (CBP) is generally caused by E. coli or other gram-negative Enterobacteriaceae and affects males aged 36 to 50. Approximately 5% of individuals with ABP will develop CBP.

- Patients may have a history of recurring urinary tract infections (UTIs), which can be episodic or chronic. UTIs are not usually linked with systemic infection symptoms. Other irritative or obstructive urologic symptoms are possible.

- CBP is a male pelvic inflammatory disorder characterized by a prolonged bacterial infection of the prostate gland and its surrounding tissues. It is a chronic and debilitating ailment that significantly reduces the patient’s quality of life.

Category III: Chronic abacterial prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome

- Chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS) is a complicated condition with an unknown cause and a poor response to treatment. CP/CPPS affects males of all ages and can have a substantial impact on patient’s quality of life and social functioning.

- In the absence of any identified reasons, chronic pelvic discomfort for at least three of the previous six months, frequently linked with urinary symptoms and/or sexual dysfunction is termed as CP/CPPS.

- It is characterized by a wide range of symptoms, including

- Pelvic discomfort

- Irritative and obstructive voiding symptoms

- Ejaculatory pain

- Sexual dysfunction

- Depression, and psychosocial maladjustment.

- The two types of CP/CPPS are inflammatory and noninflammatory.

- Characteristics of inflammatory CP/CPPS are

- The presence of white blood cells in the sperm

- Expressed prostatic secretions, or voided bladder urine following prostatic massage.

- Whereas, the lack of white blood cells indicates noninflammatory CP/CPPS.

Category IV: Asymptomatic prostatitis (histologic or andrological diagnosis)

- Asymptomatic inflammatory prostatitis is distinguished by an increase in white blood cells in the ejaculate (leukocytospermia) and an increase in prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels in the absence of infection or genitourinary symptoms.

- This disorder is typically discovered by chance during infertility workups and relates to BPH.

Causes

Acute bacterial prostatitis (ABP)

- Urethral infection, urine reflux into the prostate ducts, or direct extension or lymphatic dissemination from the rectum are risk factors.

- Gram-negative pathogens (e.g., E. coli, Enterobacter, Serratia, Pseudomonas, Enterococcus, and Proteus species) account for around 80% of the pathogens.

- It may be more common in hospitalized patients who have indwelling urethral catheters.

- Sclerotherapy for rectal prolapse may raise the risk as well.

Chronic bacterial prostatitis (CBP)

It is a primary voiding dysfunction condition, either anatomical or functional.

- E. coli (75-80%)

- Often identified: Enterococci and Pseudomonas

- Trichomonas vaginalis, Chlamydia trachomatis, Ureaplasma species

- Uncommon organisms like Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Coccidioides, as well as Histoplasma and Candida species

- Patients with renal tuberculosis may develop tuberculous prostatitis.

- Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)

- Cytomegalovirus

- Inflammatory disorders (e.g., sarcoidosis)

Chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS)

- Functional or structural bladder disease, such as

- Primary vesical neck blockage

- Pseudodyssynergia (failure of the external sphincter to relax during voiding)

- Reduced detrusor contractility

- Acontractile detrusor muscle

- Obstruction of the ejaculatory duct

- Increased tension in the pelvic side walls

- Nonspecific prostatic inflammation

Asymptomatic prostatitis

- Most likely: bacterial and viral infections

- The process behind allergic responses to stimuli such as seminal fluid and urine due to inadequate drainage and reflux into prostate tissue

- Estrogen-producing inflammatory cells

- BPH (sometimes classified as a localized autoimmune disorder)

- Age-related immune system weakness and hormonal changes (It results in suppressor cell hypofunction and subsequent invasion of inflammatory cells, resulting in asymptomatic histological inflammation).

Signs and Symptoms

Acute bacterial prostatitis

- Sudden onset of irritative (e.g., dysuria, urinary frequency, urine urgency)

- Obstructive voiding symptoms (e.g., hesitation, incomplete voiding, straining to urinate, weak stream)

- Suprapubic, rectal, or perineal discomfort

- Painful ejaculation, hematospermia, and painful defecation.

- Systemic symptoms such as fever, chills, nausea, emesis, and malaise

- Hematuria (rare)

Chronic bacterial prostatitis

Chronic bacterial prostatitis patients often have no systemic symptoms. However, these patients may present with the following symptoms:

- Intermittent dysuria

- Symptoms of intermittent obstructive urinary tract

- Recurrent UTIs

- Urinary urgency and frequency

- Urinary hesitancy or retention

- Hematuria

- Malodorous urine

- Urethral discharge

Chronic prostatitis/ chronic pelvic pain syndrome

- Pelvic pain or discomfort, including perineal, suprapubic, coccygeal, rectal, urethral, and testicular/scrotal pain, for more than three of the past six months, without confirmed uropathogen urinary tract infections

- Symptoms of an obstructed urinary tract, such as

- Frequency

- Dysuria

- Incomplete voiding

- Ejaculatory pain

- Erectile dysfunction

- Pain during or after sex

- Post-ejaculatory pain

- Abdominal pain

- Frequent urination

- Genital pain

- Lower back pain

- Pain while sitting

- Sexual dysfunction

- Unexplained fatigue

Asymptomatic inflammatory prostatitis

- No symptoms, usually diagnosed while screening for other conditions.

Pathophysiology

ABP

- Microorganisms typically always enter the prostate gland via the urethra. Bacteria often move from the urethra or bladder into the prostatic ducts, resulting in intraprostatic urine reflux.

- As a result, infection in the bladder or epididymis may occur. Uropathogenic bacterial isolates that induce prostatitis may accumulate more specific virulence factors than cystitis alone

- Direct inoculation following transrectal prostate biopsies and transurethral procedures can also cause acute prostatitis (e.g., catheterization and cystoscopy)

CBP

- The pathogenesis of chronic bacterial prostatitis is unknown, however an ascending infection from the distal urethra to the prostate is thought to be a potential.

- It may be related with increased biofilm formation and virulence factors. CBP can also be caused by seeding from the blood, lymphatics, or intestines.

- Anatomical abnormalities in the intra-prostatic channels may also explain their greater capacity to disseminate infection retrogradely.

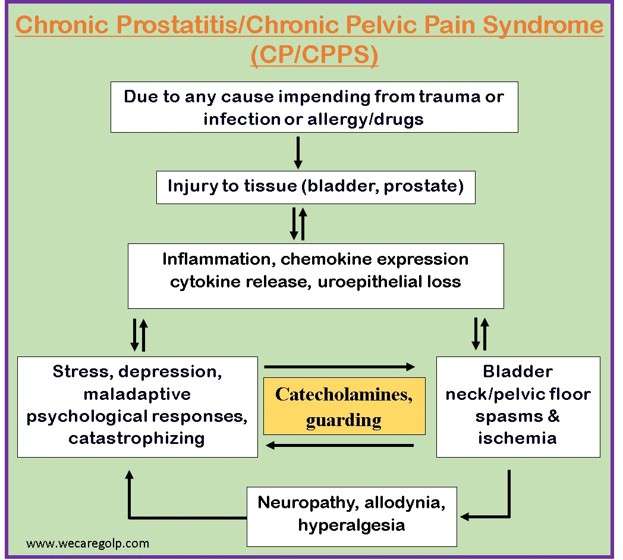

CP/CPPS

- Abnormalities in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and hormonal derangements involving the adrenocortical hormone that can originate from varying responses to stress, neurogenic inflammation, and myofascial pain syndrome.

- As a result of the inflammatory process, tissue edema and increased intra-prostatic pressure occur, resulting in local hypoxia and other mediator-induced tissue damage. This causes abnormal neurotransmission in sensory nerve fibers, resulting in pain and other symptoms of the illness.

- Abnormal local nervous system functioning, which may be caused by past trauma, illness, or anxious temperament, as well as continuous, albeit unconscious, pelvic tensing, may result in inflammation mediated by nerve cells and nerve cell-associated chemicals (e.g., substance P).

- Chronic stimulation of pelvic nerves on mast cells at the end of nerve paths can inflame the prostate (and the rest of the genitourinary tract: bladder, urethra, and testicles).

Diagnosis

The four types of prostatitis are differentiated and classified using clinical presentation and laboratory testing.

Diagnosis of ABP

When acute bacterial prostatitis is suspected, the following tests are done. Prostate massage is not recommended and may be dangerous.

- Blood cultures

- Complete blood count

- C-reactive protein

- Procalcitonin

- Prostate-specific antigen (PSA).

Diagnosis of CB/CPPS

Several particular diagnostic tests should be conducted in the diagnosis of chronic prostatitis or chronic pelvic pain syndrome. The criteria for diagnosis are based on four elements:

- Symptoms in the perineal and/or lower abdominal regions

- Prostate infection and/or inflammatory alterations with test evidence of abnormal results

- Clinical manifestations (mostly pain and discomfort) resulting from or related to the prostate and lower urinary system

- Symptoms that emerge after an inducible etiology with varying incubation durations.

Only 60% of acute prostatitis patients and 20% of chronic prostatitis patients had high PSA levels. A reduction following effective antibiotic therapy is associated with clinical and microbiological improvement.

Meares-Stamey Four-Glass Test

- No antibiotics should have been taken for one month before the test, the patient should not have ejaculated for two days, and the patient must have a full bladder.

- To avoid infection, the penis should be well washed.

- A 5 to 10 mL sample of first-void urethral urine (from the distal urethra) is collected.

- The patient excretes another 100 to 200 ml of pee before collecting 5 to 10 ml of mid-stream bladder urine.

- A one-minute massage of the prostate gland is conducted during the digital rectal examination, and any expressed prostatic secretions (EPS) are collected in a sterile container (a dry prostate massage is reasonably common).

- 5 to 10 ml of post-massage urine is collected immediately after the treatment.

- Microscopy and quantitative culture are used to evaluate all three urine samples.

- Special microbiological tests should be considered when unusual pathogens are suspected. Prostatitis caused by C. trachomatis, U. urealyticum, or T. vaginalis can be detected using molecular tests or by isolating the causal organism in EPS, semen, or urine samples after prostate massage with the lack of the organisms in the urethral swab before to ejaculation or prostate massage.

- 10 polymorphonuclear leucocytes (PMNL) per high-power field (400) is considered diagnostic for prostate inflammation. A PMNL count of 10 per high-power field larger in the last urine sample than in the first and second urine samples is indicated in cases with a dry expressate.

- To allocate an organism to the prostate, the colony count in the expressed prostatic secretions and the last urine sample must be at least ten times larger than the colony count in the first and second urine samples.

Two-Glass Test

- The four-glass test is rarely used in routine clinical practice since it is difficult to conduct, time-consuming, and uncomfortable for the patient.

- The two-glass test has the same sensitivity as the Meares-Stamey four-glass test.

- Before and after a prostate massage, urine samples are collected.

Urine and Sperm Analysis

- Microscopy and quantitative culture are used to investigate a first-void urine sample and semen.

Additional Examinations

- When a sexually transmitted illness is suspected (particularly in men under the age of 35, older men with several sexual partners, and so on), screening for C. trachomatis, Treponema pallidum, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, hepatitis B virus, and HIV should be conducted.

- Because inflammation in the gland is not consistently distributed, prostate biopsy culture is neither sensitive nor specific.

- Transrectal ultrasonography or a computer tomography scan of the gland should be conducted if a prostatic abscess is suspected.

- Abdominal ultrasound

- Cystoscopy

Treatment

ABP

- Mild or moderate disease while awaiting culture

- In addition to antibiotics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDS) may provide analgesia as well as faster healing by liquefying prostatic secretions.

- Appears septic or unable to tolerate oral therapy, admit to hospital, offer parenteral therapy with ampicillin and gentamycin or ceftriaxone as per severe pyelonephritis treatment.

- As a result of ABP, acute urine retention might occur. Because urethral catheterization may aggravate infection and is contraindicated, a suprapubic tap should be done to relieve retention.

- To minimize seeding of the blood and bacteremia in acute bacterial prostatitis, avoid recurrent prostate inspections.

- In situations of prostatic abscess, the fluctuant location may be drained transrectally or transperineally under local anesthesia. A pigtail catheter can be introduced as a drain during transperineal surgery. With the patient under anesthesia, cystoscopic, transurethral abscess unroofing is also possible.

CBP

- In chronic bacterial prostatitis, a 4- to 6-week trial of antibiotic treatment is recommended

- Recurrences of chronic bacterial prostatitis are prevalent, presumably because few antibacterial medicines reach adequate concentrations in the prostatic tissue to eliminate infections.

- Analgesics (especially nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medicines [NSAIDs]), alpha-blocking agents, hydration, stool softeners, and sitz baths are frequently used as supportive therapy.

- Alpha-blockers diminish bladder outlet blockage and thereby improve voiding dysfunction, which may be linked with prostatitis-related prostatic enlargement.

- Transurethral resection or complete prostatectomy may result in a cure in circumstances when infected prostatic calculi act as a nidus.

- If antibiotics, NSAIDs, and alpha blockade have not provided relief, make certain that the patient is referred to a urologist as soon as possible.

- In critically unwell patients, treat concomitant septicemia with caution. Keep an eye out for bladder outlet blockage and renal failure.

- If urination problems persist and incomplete bladder urine emptying is suspected, refer the patient to a urologist for an examination of urination with flow rate and postvoid residual urine testing.

- Saw palmetto, quercetin, regular sitz baths, perianal massage, and frequent ejaculation may also assist to remove prostatic secretions and relieve pain.

First-line treatment

- Norfloxacin 400 mg orally every 12 hours for 4 weeks, or

- Trimethoprim 300 mg orally daily for 4 weeks

If chlamydia or ureaplasma noted

- Doxycycline 100 mg orally every 12 hours for 2–4 weeks

CP/CPPS

- It is treated similarly as chronic bacterial prostatitis.

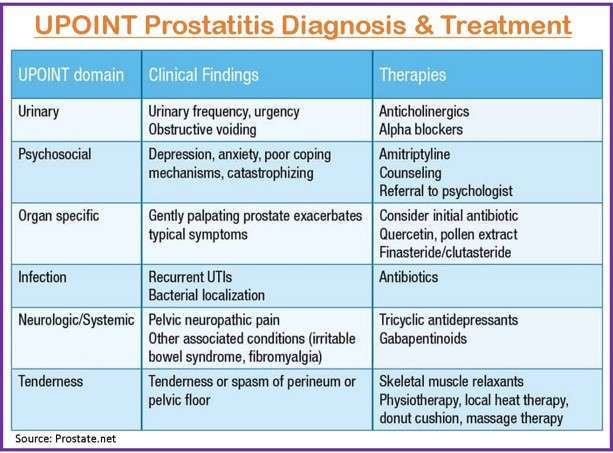

- Men with CPPS have a variety of symptoms. Furthermore, the severity of symptoms varies. Researchers created a classification (the UPOINT classification) to divide patients into subgroups based on which symptoms prevail.

- The objective is that by identifying the collection of symptoms unique to each patient, therapy may be more precisely customized. Furthermore, classification enables research into the effectiveness of various drugs and therapies depending on symptom groupings.

- The UPOINT categorization uses a 6-point system, as follows:

- U – Urinary symptoms

- P – Psychosocial symptoms

- Organ-specific symptoms (such as the prostate)

- I – Infection-related symptoms

- N – Neurologic/systemic symptoms

- T – Tenderness in the muscles and pelvic floor symptoms

Asymptomatic Inflammatory Prostatis

- This condition is typically diagnosed by chance during infertility workups and is connected with BPH.

- Though some physicians will treat this disease with antibiotics to prevent occult infection, there is little evidence to support this approach, and therapy is unnecessary owing to the absence of clinical symptoms

Prevention

- The main methods include actively treating general infection and secondary infection of the prostate, modifying diet and lifestyle, avoiding unnecessary medical examinations, establishing good coping styles, publicizing prostate, and prostate-related disease knowledge, and strengthening prevention in post-prostatitis patients.

- Protection against sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) also protects against several organisms linked to acute bacterial prostatitis, chronic prostatitis development, and nonbacterial prostatitis causes.

- Men who report symptoms of CB have been linked to psychological stress. Recognizing underlying psychosomatic disorders in chronic instances, as well as proper psychiatric referral and treatment, reduce the likelihood of recurrence.

- Treatment for UTIs as soon as possible may prevent the infection from spreading to the prostate.

- Many measures exist to prevent prostatitis from forming, including keeping the body properly hydrated, avoiding unnecessary catheterization, maintaining excellent glycemic control, avoiding smoking and excessive alcohol usage, and avoiding extended urine holding.

Prognosis

- With strong antibiotic therapy and high patient compliance, individuals with the initial onset of ABP have a favorable prognosis. Inadequate antibiotic therapy raises the risk of infertility, epididymitis, chronic prostatitis, and prostatic abscess development.

- Causative underlying variables may alter the overall prognosis in people with CB who have acute exacerbations.

- Prostatitis can progress to urosepsis, which has a high mortality rate in patients with diabetes, dialysis for chronic renal failure, immunocompromised individuals, and postsurgical patients who have had urethral instrumentation. Prostate cancer has not been clearly linked to CP or asymptomatic inflammatory prostatitis.

Summary

- Prostatitis is microscopic inflammation of the prostate gland tissue characterized with various clinical symptoms.

- Depending on the bacterial and abacterial and acute and chronic infection, the disease is classified into four categories (I, II, III, and IV).

- Among four categories, chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS) is the most common prostatitis worldwide.

- Treatment for UTIs as soon as possible may prevent the infection from spreading to the prostate.

References

- Cho, I. C., & Min, S. K. (2015). Proposed new pathophysiology of chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Urogenital Tract Infection, 10(2), 92-101. https://synapse.koreamed.org/articles/1084189

- Coker, T. J., & Dierfeldt, D. (2016). Acute bacterial prostatitis: diagnosis and management. American family physician, 93(2), 114-120. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26926407/

- Khan, F. U., Ihsan, A. U., Khan, H. U., Jana, R., Wazir, J., Khongorzul, P., Waqar, M., & Zhou, X. (2017, Oct). Comprehensive overview of prostatitis. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, 94, 1064-1076. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.08.016

- Magri, V., Boltri, M., Cai, T., Colombo, R., Cuzzocrea, S., De Visschere, P., … & Wagenlehner, F. M. (2018). Multidisciplinary approach to prostatitis. Archivio Italiano di Urologia e Andrologia, 90(4), 227-248. doi: 10.4081/aiua.2018.4.227

- Nickel, J. C. (1999). Textbook of prostatitis. CRC Press. https://books.google.com.np/books?hl=en&lr=&id=YiZz_xDk7rkC&oi=fnd&pg=PP11&dq=Prostatitis+J.+Curtis+Nickel,+MD,+FRCSC&ots=LGJNHJZv–&sig=j1a1M5vpCkKO4IpGj0JXONZ9khQ&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=Prostatitis%20J.%20Curtis%20Nickel%2C%20MD%2C%20FRCSC&f=false

- Nickel, J. C., Tripp, D., Gordon, A., Pontari, M., Shoskes, D., Peters, K. M., … & Baranowski, A. P. (2011). Update on urologic pelvic pain syndromes: highlights from the 2010 international chronic pelvic pain symposium and workshop, august 29, 2010, Kingston, Ontario, Canada. Reviews in urology, 13(1), 39-49. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3151586/

- Sharp, V. J., Takacs, E. B., & Powell, C. R. (2010). Prostatitis: diagnosis and treatment. American family physician, 82(4), 397-406. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20704171/

- Vaidyanathan, R., & Mishra, V. C. (2008, Jan-Mar). Chronic prostatitis: Current concepts. Indian Journal of Urology: IJU: Journal of the Urological Society of India, 24(1), 22-27. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2684227/#!po=18.2927

- Zhang, Z., Li, Z., Yu, Q., Wu, C., Lu, Z., Zhu, F., Zhang, H., Liao, M., Li, T., Chen, W., Xian, X., Tian, A., & Mo, Z. (2015, Nov 13). The prevalence of and risk factors for prostatitis‐like symptoms and its relation to erectile dysfunction in Chinese men. Andrology, 3(6), 1119-1124. https://doi.org/10.1111/andr.12104