Introduction

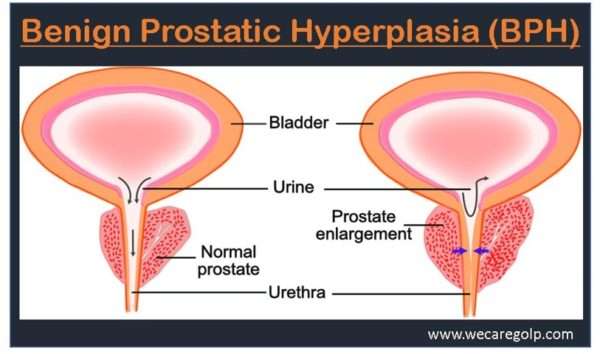

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) refers to the nonmalignant enlargement or hyperplasia of prostate tissue and is a major cause of lower urinary tract symptoms in men. With age, the prevalence of the disease rises. Indeed, the histological prevalence of BPH at autopsy ranges from 50% to 60% in men in their 60s to 80% to 90% in those over 70 years.

- BPH defines the histological alterations, BPE (Benign Prostate Enlargement) indicates the enlarged size of the gland (typically secondary to BPH), and Bladder outlet obstruction (BOO) describes the obstruction to flow.

- Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) are essentially urine symptoms shared by bladder and prostate illnesses (when in reference to men).

- LUTS can be classified into storage and voiding symptoms.

- These words have essentially superseded those formerly known as “prostatism.”

- BPH is characterized by stromal and epithelial cell proliferation in the prostate transition zone (surrounding the urethra), which leads to urethral compression and the development of bladder outflow obstruction (BOO). It can result in clinical manifestations of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), urinary retention, or infections due to incomplete bladder emptying.

- Long-term untreated illness can result in persistent high-pressure retention (a potentially fatal emergency) and long-term alterations to the bladder detrusor (both overactivity and reduced contractility).

Prostate

- The prostate could be a walnut-sized secretor that forms a part of the male genital system.

- It is just distal to the urinary bladder and anterior to the rectum.

- It is part of the urinary tract and links directly to the penile urethra.

- It is consequently a channel between the bladder and the urethra.

- The gland is made up of many zones or lobes that are surrounded by a layer of tissue on the outside (capsule).

- The peripheral, central, and anterior fibromuscular stroma and transition zones are among them.

- BPH develops in the transition zone that surrounds the urethra.

- Its primary function is to produce an alkaline solution that protects sperm in the acidic environment of the vagina.

- The fluid serves to regulate the acidity of the vagina, which enhances the total longevity of the sperm, enabling the largest length of time to fertilize an egg effectively.

- The fluid also includes proteins and enzymes that sustain and feed sperm.

- The increased amount of prostatic fluid in comparison to seminal fluid and sperm allows for more efficient mechanical propulsion through the urethra.

Incidence

- BPH is a prevalent issue that impairs the quality of life in one-third of men over the age of 50.

- BPH is histologically visible in up to 90% of males by the age of 85 years.

- BPH symptoms affect up to 14 million men in the United States.

- Around 30 million men worldwide suffer from BPH symptoms.

- The frequency of BPH is comparable in white and African-American males.

- However, BPH in African-American males is more severe and progressive, presumably because of greater testosterone levels, 5-alpha-reductase activity, androgen receptor expression, and growth factor activity in this community.

- Increased activity causes a rise in the rate of prostatic hyperplasia, enlargement, and associated complications.

- Among many nations, benign prostatic hyperplasia has been recognized as a serious urological health concern in elderly men.

- According to descriptive epidemiology studies, the prevalence of benign prostatic hyperplasia ranges from 12% to 42%, and one research assessed the lifetime risk of benign prostatic hyperplasia to be 29%.

Causes of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia

In addition to the direct secretion actions of testosterone on prostate tissue, the etiology of benign prostatic hyperplasia is compacted by a wide range of risk factors.

- Although they do not directly cause BPH, testicular androgens have a role in its development, with dihydrotestosterone (DHT) interacting directly with the prostatic epithelium and stroma.

- Testosterone generated in the testes is converted to dihydrotestosterone (DHT) in prostate stromal cells by 5-alpha-reductase 2 and accounts for 90% of total prostatic androgens. DHT has direct effects on stromal cells in the prostate, paracrine effects on neighboring prostatic cells, and endocrine effects in the bloodstream, which impact both cellular proliferation and apoptosis (cell death).

- Estrogens – Throughout the lives, men produce testosterone, an important male hormone, and small amounts of estrogen, a female hormone. As men get older, there is less active testosterone, leaving more estrogen in the blood. Studies done in animals show that BPH may occur with a higher amount of estrogen within the gland, which makes substances that promote cell proliferation.

Risk Factors of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia

- Non-modifiable and modifiable risk factors all have a role in the development of BPH. It is becoming increasingly clear that modifiable lifestyle variables have a significant impact on the natural history of BPH.

- Although the patterns are variable, there are some suggestions that both macronutrients and micronutrients may influence the risk of BPH.

- Increased total energy intake, energy-adjusted total protein intake, red meat, fat, milk and dairy products, cereals, bread, poultry, and starch are all potential risk factors for clinical BPH and BPH surgery.

- Whereas vegetables, fruits, polyunsaturated fatty acids, linoleic acid, and vitamin D are potential risk factors for BPH.

- Higher circulation amounts of vitamin E, lycopene, selenium, and carotene are inversely related to BPH.

- Exercise and increased physical activity are consistently connected to reduced risks of BPH surgery, histological BPH, clinical BPH, und LUTS.

Age

- According to research, the risk of BPH increases with age.

- Symptoms often appear around the age of 50, and by the age of 60, the majority of men have some degree of prostate enlargement.

- However, in some individuals, the illness is asymptomatic and may go unnoticed.

Metabolic Syndrome

- Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is a collection of metabolic disorders associated with central obesity and insulin resistance.

- Its significance is growing since it is linked to an increased risk of metabolic and cardiovascular illnesses.

- MetS abnormalities can cause BPH and LUTS in males.

Obesity

- Obesity has been linked to an increased risk of BPH in observational studies.

- The actual reason is uncertain but is likely complex in nature since obesity makes up one element of the metabolic syndrome.

- Increased levels of estrogen and systemic inflammation belong to the proposed causes.

- Furthermore, obesity raises intra-abdominal pressure, which increases bladder pressure and intravesical pressure.

- Thus, it results in exacerbating and worsening BPH symptoms.

Hypertension

- Comorbidities such as BPH and hypertension are widespread; around 25%-30% of all men over the age of 60 have both BPH and hypertension.

- Several research have found a link between benign prostate hyperplasia and hypertension via insulin-like growth factor activation and increased sympathetic nervous system activity.

Hereditary Factors

- BPH is influenced by genetics.

- Men who have a first-degree family with BPH, such as a father or brother, are more likely to acquire the condition than men who do not have a first-degree relative with BPH.

Signs and Symptoms of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia

Usually, pain and dysuria are not present in benign prostatic hyperplasia. The symptoms of BPH are classified as storage and voiding.

Storage symptoms

- Urinary frequency

- Urgency

- Incontinence and

- Voiding at night.

Voiding symptoms

- Weak urinary stream

- Hesitancy while waiting for the stream to begin or stops intermittently

- Straining to void and

- Dribbling.

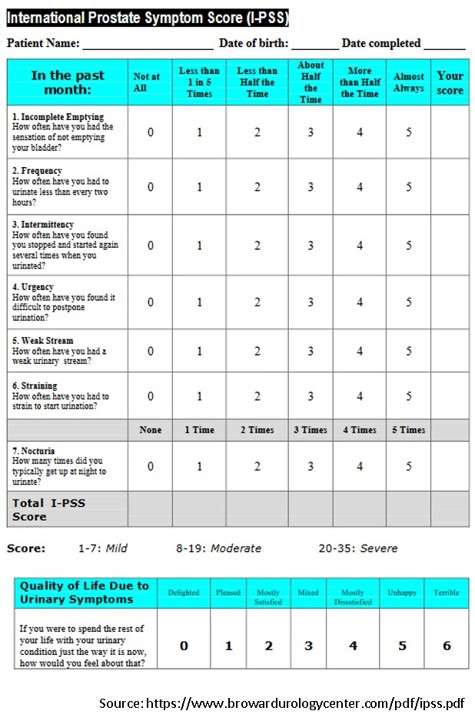

International Prostate Symptom Score (I-PSS)

The storage and voiding symptoms are evaluated using the international prostate symptom score (I-PSS) questionnaire, designed to assess the severity of BPH.

- The I-PSS is predicated on the answers to seven questions about urinary symptoms and one question involving quality of life.

- Every question on urinary symptoms permits the patient to pick out one in all six answers reflecting the severity of the issue.

- The answers are graded on a scale of 0 to 5. The total score might thus vary from 0 to 35 (asymptomatic to very symptomatic).

Other clinical presentation

- Incomplete bladder emptying – The feeling of persistent residual urine, regardless of the frequency of urination

- Straining – The need strain or push (Valsalva maneuver) to initiate and maintain urination in order to empty the bladder more fully

- Decreased force of stream – The subjective loss of force of the urinary stream over time

- Dribbling – The loss of small amounts of urine due to a poor urinary stream as well as weak urinary stream

Pathology and Pathogenesis of BPH

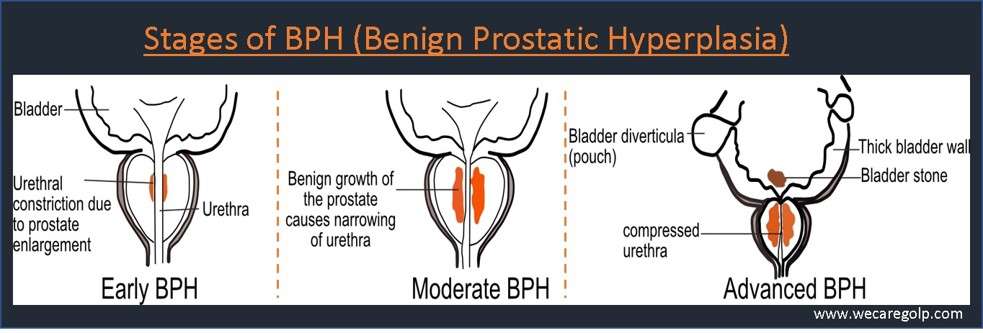

- With increasing age, the prostate gland undergoes benign enlargement first around the prostatic urethra and later extends to involve the central zone.

- The weight of the prostate gland in BPH is usually 2-3 times more.

- Grossly, nodular enlargements with cystic spaces due to dilatation of the obstructed prostatic ducts. It is also important to note that with advancing age, cancer of the prostate gland may occur. It commonly arises from the peripheral zone.

- The hormonal mechanism, an increase in the level of Dihydrotestosterone (DHT) in the cells leads to stimulation of cell growth.

- DHT is derived from testosterone by the enzymatic action of 5α-reductase. Both mechanical enlargements of the prostate gland as well as an increase in the tone of the prostatic urethra cause bladder outlet obstruction in BPH.

Sequelae of BPH

- Bladder outlet obstruction causes hypertrophy of the detrusor muscle and thickening of the bladder due to increasing workload against the outflow resistance.

- Usually, the thin and fibrous outer capsule of the prostate becomes thick and spongy as it enlarges.

- The prostatic urethra becomes compressed and narrowed, causing the bladder musculature to work harder to empty urine.

- The bladder begins to contract with even small amounts of urine, leading to more frequent urination.

- Eventually, the bladder weakens and loses the ability to empty itself, so residual urine remains in the bladder.

- The narrowing of the urethral and partial emptying of the bladder cause many problems associated with BPH.

- In the early phase of bladder outlet obstruction, the flow rate is maintained with the increase in the emptying pressure.

- This is known as compensatory hypertrophy.

- As the obstruction progresses, the detrusor pressure rises further, and the flow rate decreases with a large amount of residual urine in the bladder. Moreover, fibrous tissue replaces the detrusor muscle. Hence, the detrusor muscle becomes floppy with poor tonicity.

- In the late phase (also called decompensatory hypertrophy), the bladder is now suffering from irreversible damage.

- In the late phase (also called decompensatory hypertrophy), the bladder is now suffering from irreversible damage.

- When the obstruction is not relieved by appropriate treatment, hydronephrosis, hydroureter, and renal failure can occur.

- As a result of increased residual urine, stasis can lead to stone formation in the bladder and is seen in about 10% of patients with BPH locally.

- Infection is also commonly seen at this stage and would be difficult to eradicate until the obstruction is relieved.

- About 3-5% of patients with BPH present with chronic retention, and overflow incontinence is usually associated with impairment of renal function.

Diagnosis of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia

- History taking to determine the severity of the symptoms.

- Physical examination (digital rectal examination) helps to determine the size and condition of the gland.

- In addition to history taking and physical examination, laboratory and non-laboratory tests may include diagnosing BPH.

Laboratory Tests

- Blood urea, nitrogen, and creatinine, electrolytes: These tests are beneficial for screening for chronic kidney disease in individuals with high postvoid residual (PVR) urine volumes. However, a regular serum creatinine measurement is not recommended in the first examination of males with BPH-related lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS).

- Urinalysis/Urine culture: Urinalysis implies examining the urine using dipstick techniques and/or by centrifuged sediment examination to test for the presence of blood, leukocytes, bacteria, protein, or glucose. A urine culture may be beneficial to eliminate infectious causes of irritative voiding and is generally conducted if the first urinalysis findings show an abnormality.

- PSA (Prostate-specific antigen): It helps detect prostate cancer. Although BPH does not cause prostate cancer, men, who are at risk for BPH, are at risk for this illness as well. Thus, it should be tested accordingly. Normal range of PSA is 0.2-0.4 mg/ml.

Other Nonlaboratory Tests

- Ultrasonography: In patients with urinary retention or symptoms of renal insufficiency, abdominal, renal, and transrectal ultrasonography can assist estimate bladder and prostate size as well as the degree of hydronephrosis (if any). In general, it is not recommended for the first assessment of simple LUTS.

- Cystoscopy: Cystoscopy may be appropriate in patients scheduled for invasive treatment or in whom a foreign body or malignancy is suspected. Endoscopy may also be recommended in individuals who have a history of sexually transmitted illness (e.g., gonococcal urethritis), extended catheterization, or trauma.

- Flow rate: It helps identify the patient’s reaction to therapy and is useful in the first evaluation.

- PVR urine volume: It measures invasively with a catheter or noninvasively with a transabdominal ultrasonic scanner to assess the degree of bladder decompensation.

- Pressure-flow investigations – The results may be useful in determining BOO.

- Urodynamic investigations – To assist distinguish between BOO and weak bladder contraction capacity (detrusor underactivity).

- Urine cytology – This may be investigated in people who have mostly irritative voiding symptoms.

Management of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia

Watchful Waiting/Active Surveillance

- During this period, a patient does not receive any active treatment, but the physician monitors him closely.

- The patient gets yearly routine screening to avoid BPH progression.

- For patients who have mild or moderate to severe symptoms (I-PSS) but are not bothered by their symptoms and are not experiencing BPH complications, watchful waiting is recommended strategy. Medical therapy is unlikely to enhance the patients’ symptoms or quality of life (QOL).

Medical Therapies

Alpha Blockers

- The prostate stromal smooth muscle and bladder neck contain alpha 1-adrenoreceptors. Blocking alpha 1-adrenoreceptors causes stromal smooth muscle relaxation, which addresses the dynamic component of BPH and so improves flow. Tamsulosin (400mcg once a day) and Alfuzosin are two examples of selective Alpha-blockers (10mg once daily).

- Although alpha-blockers may relieve the BPH symptoms, they usually are ineffective in reducing prostate size. They have almost immediate action and can take orally once or twice a day.

- Commonly prescribed alpha blockers include alfuzosin, terazosin, doxazosin, or tamsulosin.

5-alpha-reductase Inhibitors

- Finasteride (5mg once a day) and dutasteride are alpha-reductase inhibitors that prevent testosterone from being converted to DHT. This tackles the static component of BPH by promoting the shrinking of the prostate and takes several weeks to demonstrate appreciable improvement, with six months needed for optimal success. The treatment serum can lower PSA levels by 50% and reduce prostate volume by up to 25%. It alters the illness process and subsequent disease development.

Combination Therapy

- The combined use of 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors and alpha-blockers has shown to be superior to single-drug therapies in men with larger prostates.

- It prevents disease progression and improves annoying symptoms.

- However, this enhanced benefit may come with more side effects (possible side effects from both medications).

Antimuscarinics

- In individuals with progressive bladder outlet blockage, bladder detrusor instability might occur. It can cause increased urgency and frequency (overactive bladder).

- Muscarinic receptor antagonists, which inhibit muscarinic receptors on detrusor muscle, can alleviate these symptoms.

- It lowers smooth muscle tone and can relieve symptoms in persons with overactivity. Solifenacin, tolterodine, and oxybutynin are few examples.

- Alternatively, mirabegron (a Beta-3 adrenoreceptor agonist) may use if antimuscarinic medication fails. It promotes detrusor relaxation.

Minimally Invasive Procedures of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia

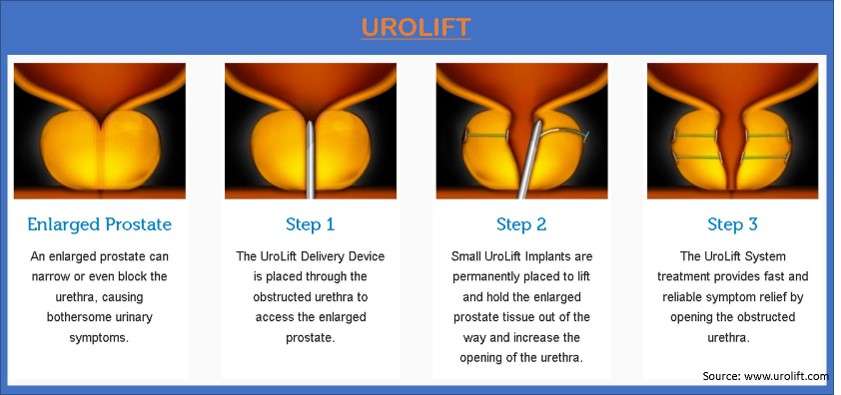

Urolift (Prostatic Urethral Lift)

- Urolift is a tissue-saving technique.

- It can help limit the risk of bleeding in co-morbid patients and the related hazards of more invasive surgery (such as anesthesia risk, prolonged surgery time, etc.).

- Squeezing the lobes of the prostate can enlarge the channel in the prostatic urethra, improving LUTS.

- Studies have indicated advantages, including the potential of day-case surgery, intact sexual function, better symptom scores (IPSS), and flow rates (QMax).

Transurethral Electrovaporization

- A urologist uses an electrode-attached resectoscope (tubelike instrument) to the prostate through the urethra.

- The electric current of the electrode transfers to the prostate and then vaporizes prostate tissue.

- The effect of vaporization drills below the surface area of affected tissue and blocks blood vessels.

Transurethral Microwave Thermotherapy

- A urologist uses a catheter to the prostate through the urethra.

- Through the catheter, microwaves will send to heat the target portions of the prostate tissue.

High-intensity Focused Ultrasound

- A urologist uses a special ultrasonic transducer into the rectum that provides heat to the prostate.

- This heat destroys the enlarged tissue of the prostate.

Transurethral Needle Ablation

- A urologist uses a cystoscope and needles into the prostate through the urethra.

- With the help of the needles, radiofrequency energy will send to the urethra, which heats and destroys target portions of the affected prostate tissue.

Prostatic Stent Insertion

- A small device, a stent, widens the urethra pushing the prostate tissue back.

- Usually, this method could be the last alternative if the patient cannot be suitable for other treatment procedures.

Water-induced Thermotherapy

- This treatment destroys the prostate tissue using heated water.

- It uses a special catheter inserted into the urethra.

- Through the catheter, the heated water flows into the treatment balloon.

- This process causes rapid cell death in the target area.

Surgical management of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia

The European Association of Urology (EAU) guidelines for surgical indications in BPH are as follows:

- Refractory urinary retention

- Recurrent urinary infection

- Refractory hematuria to medical therapy (other causes excluded)

- Renal insufficiency

- Stones in the bladder

- Chronic high-pressure retention (absolute indication)

- Increased post void residual

Transurethral Incision of the Prostate (TUIP)

- A TUIP is a surgical procedure to widen the urethra.

- It reduces the pressure of the prostate on the urethra and allows the urine to flow easily.

- A urologist makes a small incision and inserts a cystoscope and an instrument with an electric knife or laser to reduce the pressure.

- However, TUIP is only effective in treating patients with smaller prostates.

Transurethral Resection of the Prostate (TURP)

- A gold standard procedure, TURP is the commonest surgical treatment for BPH.

- A urologist uses a resectoscope through the urethra.

- A wire loop cuts the enlarged prostate tissue into pieces and seals blood vessels using a resectoscope.

- The cut prostate tissue irrigates into the bladder, which flushes out at the end of the procedure through the urine catheter.

Holmium Laser Enucleation of the Prostate (HoLEP)

- HoLEP, a laser therapy, needs no incision.

- A urologist uses a laser through a resectoscope into the prostate and destroys the excess prostate tissue.

- HoLEP can be an indication for patients who have a high risk of bleeding after surgery.

- However, it might not work for a significantly enlarged prostate.

Open Prostatectomy

- In this treatment, a urologist removes all or part of the prostate via surgery.

- It can be retropubic, suprapubic, and perineal prostatectomy.

- The major complications are blood loss.

- Consequently, it may need a blood transfusion and a longer hospital stay.

- It is the operation of choice when the transurethral surgery cannot cure the BPH due to greatly enlarged prostate.

Complications of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia

- Obstructive uropathy

- Gross hematuria

- UTI (Urinary Tract infection)

- Hydroureter

- Hydronephrosis, cystolithiasis

- Bladder hypertrophy

- Trabeculation

- Diverticula formation

Surgical Complications includes:

- Impotence

- Incontinence

- Retrograde ejaculation (ejaculation of semen into the bladder rather than through the penis)

- The necessity for a second operation (in 10% of patients after five years) due to continuing prostate development or a urethral stricture caused by surgery.

- Post-operative complications are hemorrhage, bladder spasm, dribbling, and infection.

Prevention of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia

Primary Prevention

- Primary disease preventive measures attempt to avoid histological BPH and the development of clinically relevant BPH.

- Weight loss, regular physical activity, vegetable consumption, alcohol intake, 5α-reductase inhibitors, avoidance of overweight, and decrease of fatty food might minimize the chance of histology and clinical BPH.

- For primary disease prevention, evidence quality is inadequate, and early therapy with 5α-reductase inhibitors has not been authorized.

- Avoid postponing urination: delaying urination can increase BPH symptoms and lead to additional issues such as urinary tract infections.

- Certain over-the-counter drugs should be avoided: antihistamines and decongestants might exacerbate BPH symptoms.

- Limit alcohol consumption: while one or two alcoholic drinks per day are normally safe, excessive consumption might irritate the prostate.

- Maintain a healthy lifestyle: Some behaviors, such as smoking and poor sleep hygiene, might have a detrimental impact on prostate health.

Secondary Prevention

- Secondary preventative methods aim to stop disease development and BPH-related consequences.

- Regular and long-term use of 1-blockers decreases lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) and slows disease development. But it does not prevent BPH-related problems (e.g., urinary retention or need for prostate surgery).

- Although 5-reductase inhibitors can lower the likelihood of symptomatic disease development, urinary retention, or the necessity for surgery, the combination of a 1-blocker and a 5-reductase inhibitor is more effective than either alone.

- Secondary disease prevention methods benefit older men, particularly those with enlarged prostates (>40 cm) and increased blood PSA concentrations (>1.6 g/l).

- For secondary illness prevention, males with risk factors of disease development should utilize a medication comprising 5α-reductase inhibitors.

Prognosis

- People suffering from BPH have a pretty favorable prognosis. Although there is no cure for BPH, therapies can help ease symptoms.

- Mild symptoms may not necessitate medical attention. More severe instances can treat with medications, surgery, and minimally invasive therapies. However, therapy is only necessary if symptoms become unbearable.

- By the age of 80, 20% to 30% of men have BPH symptoms severe enough to necessitate treatment.

- If it remains untreated for a long period, it can result in persistent high-pressure retention (a potentially fatal emergency) and long-term alterations to the bladder detrusor (both overactivity and reduced contractility).

Summary

- The most common benign tumor in males is benign prostatic hyperplasia (noncancerous growth of the prostate gland). BPH has a complex etiology that includes smooth muscle hyperplasia, prostatic enlargement, and bladder dysfunction, as well as a central nervous system input.

- BPH causes urinary difficulty and intermittency, a weak urine stream, nocturia, frequency, urgency, and the sense of an incomplete bladder emptying. These symptoms, known as “lower urinary tract symptoms,” or LUTS, can have a major impact on one’s quality of life.

- Urinalysis, prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level, and International Prostate Symptom Score are strong diagnostic tools in the relevant patient population.

- Men with no or mild symptoms, as well as those who handle moderate symptoms well, may be treated without medication (“watchful waiting”). Medical therapies for patients with moderate or severe symptoms include alpha-1-AR antagonists, 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors (5-aRIs), or combination therapy with one medicine from each of these groups.

References

- Dai, X., Fang, X., Ma, Y., & Xianyu, J. (2016). Benign prostatic hyperplasia and the risk of prostate cancer and bladder cancer: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Medicine, 95(18).

- Grossfeld, G. D., & Coakley, F. V. (2000). Benign prostatic hyperplasia: clinical overview and value of diagnostic imaging. Radiologic Clinics of North America, 38(1), 31-47.

- Kim, E. H., Larson, J. A., & Andriole, G. L. (2016). Management of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Annu Rev Med, 67(1), 137-151.

- Lim, K. B. (2017). Epidemiology of clinical benign prostatic hyperplasia. Asian journal of urology, 4(3), 148-151.

- Lokeshwar, S. D., Harper, B. T., Webb, E., Jordan, A., Dykes, T. A., Neal Jr, D. E., … & Klaassen, Z. (2019). Epidemiology and treatment modalities for the management of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Translational andrology and urology, 8(5), 529.

- Madersbacher, S., Sampson, N., & Culig, Z. (2019). Pathophysiology of benign prostatic hyperplasia and benign prostatic enlargement: a mini-review. Gerontology, 65(5), 458-464.

- McNicholas, T., & Mitchell, S. (2006). Benign prostatic hyperplasia. Surgery (Oxford), 24(5), 169-172.

- Pinto, J. D. O., He, H. G., Chan, S. W. C., & Wang, W. (2016). Health‐related quality of life and psychological well‐being in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia: An integrative review. Japan Journal of Nursing Science, 13(3), 309-323.

- Pizzorno, J. E., Murray, M. T., & Joiner-Bey, H. (2016). The Clinician’s handbook of natural medicine E-book. Elsevier Health Sciences.

- Roehrborn, C. G. (2005). Benign prostatic hyperplasia: an overview. Reviews in urology, 7(Suppl 9), S3.

- Roper, W. G. (2017). The prevention of benign prostatic hyperplasia (bph). Medical Hypotheses, 100, 4-9.

- Steers, W. D., & Zorn, B. (1995). Benign prostatic hyperplasia. Disease-a-Month, 41(7), 437-497.

- Thorpe, A., & Neal, D. (2003). Benign prostatic hyperplasia. The Lancet, 361(9366), 1359-1367.