Introduction

Pyelonephritis refers to a type of urinary tract infection (UTI) caused by bacteria that ascend from the lower to upper ranges of the genitourinary system, such as the kidney. It is a bacterial infection in the kidney and renal pelvis- the upper urinary tract. An ascending UTI, which spreads from the bladder to the kidneys and their collecting systems, results in the complication of pyelonephritis.

- Short-term morbidity from pyelonephritis includes shock and septicemia, as well as acute kidney parenchymal damage. Acute pyelonephritis can cause permanent kidney damage, which is more common in children who have several episodes or have vesicoureteral reflux (VUR).

- The word “urosepsis,” is used interchangeably in cases of severe infection (sepsis being a systemic inflammatory response syndrome due to infection). Antibiotics are needed as treatment, along with addressing any underlying causes, to stop recurrence. It is a form of nephritis. It can also be called pyelitis.

Epidemiology

- Pyelonephritis affects 250,000 people each year and accounts for over 100,000 hospitalizations. Affects 120-130 women per 100,000 and 30-40 males per 100,000 each year.

- The yearly incidence of pyelonephritis in women aged 15 to 34 years is 25 cases per 10,000 women.

- In the female population, the yearly outpatient pyelonephritis rate is 12-13 per 10,000, while the inpatient rate is 3-4 per 10,000.

- In the male population, the yearly outpatient pyelonephritis rate is 2-3 per 10,000, while the hospital rate is 1-2 per 10,000.

Classification

Acute pyelonephritis

- Acute pyelonephritis is a bacterial infection that causes inflammation of the kidney (especially the renal parenchyma) and is one of the most prevalent renal infections.

- It is a potentially fatal illness that causes renal scarring.

- This is an exudative purulent localized inflammation of the renal pelvis and kidney.

- It manifests as a pus-filled interstitium abscess, also known as suppurative necrosis: cell debris, fibrin, neutrophils, and central germ colonies (hematoxylinophil).

- Bacteria normally enter the kidney via the lower urinary tract. Bacteria can potentially enter the kidney through the bloodstream.

- Exudate damages tubules, which may include neutrophil casts.

- The glomerulus and vasculature are normal in the early stages.

- Gross pathology frequently indicates pathognomonic radiations of hemorrhage and suppuration across the renal pelvis to the renal cortex.

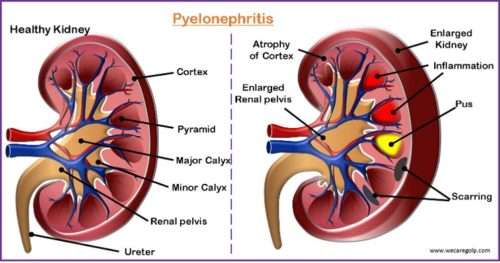

- In other words, enlarged kidneys and inflammatory cell interstitial infiltrations are typically signs of acute pyelonephritis.

- There may be an abscess on the renal capsule and at the corticomedullary junction. Eventually, tubule and glomeruli atrophy and destruction may occur.

- Acute complicated pyelonephritis is the form that arises in people with established urinary tract anatomical abnormalities, pregnant or postmenopausal women, or in the context of a condition such as uncontrolled diabetes mellitus.

- Acute complicated pyelonephritis necessitates the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics for an extended period.

Chronic pyelonephritis

- Chronic pyelonephritis is characterized by

- Chronic or recurrent renal infections

- VUR

- Urinary tract blockage.

- It can lead to scarring of the renal parenchyma and reduced function, particularly in the presence of obstruction.

- A perinephric abscess and/or pyonephrosis may develop in severe cases of pyelonephritis.

- To put it another way, this disease is characterized by both overlying cortical scarring and abnormal caliceal structures. The scar tissue results in a decrease in number of functioning nephrons and the contraction of the kidney.

- Imaging techniques such as ultrasonography or CT scanning are used to diagnose persistent pyelonephritis. It nearly always develops in individuals with significant anatomic defects, most frequently in young children with VUR.

Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis

- This is an unusual form of chronic pyelonephritis characterized by granulomatous abscess formation, severe kidney destruction, and a clinical picture that may resemble renal cell carcinoma and other inflammatory renal parenchymal diseases.

- The majority of patients have a recurrent fever, urosepsis, anemia, and a painful renal mass. Other typical symptoms include kidney stones and renal function loss in the damaged kidney.

- The bacterial cultures of renal tissue yield positive results. On the other hand, microscopic examinations of the organ can reveal lipid-laden macrophages and granulomas.

- It is found in roughly 20% of specimens from surgically managed cases of pyelonephritis.

Emphysematous pyelonephritis

- Emphysematous pyelonephritis is a severe life-threatening infection of the renal parenchyma with gas-forming bacteria (overall mortality rate of roughly 50%).

- Diabetes mellitus is prevalent in up to 90% of individuals who develop emphysematous pyelonephritis.

- Clinically, patients have variable degrees of

- Renal failure

- Lethargy

- Acid-base imbalances

- Hyperglycemia.

- In around 70% of cases, E. coli is the causative bacterial source.

Causes

- The spread of an infection in the lower parts of the urinary tract up through the ureters

- Cystitis

- Prostatitis

- Recurrent UTI

- Gram-negative bacteria

- Escherichia coli (70%- 80% of UTIs)

- Proteus, Klebsiella

- Staphylococcus saprophyticus

- Enterococcus.

- Urinary tract obstruction (kidney stone)

- Bladder catheterization or surgery

- Blood infections such as sepsis or endocarditis

- Lymphatic infection (rare)

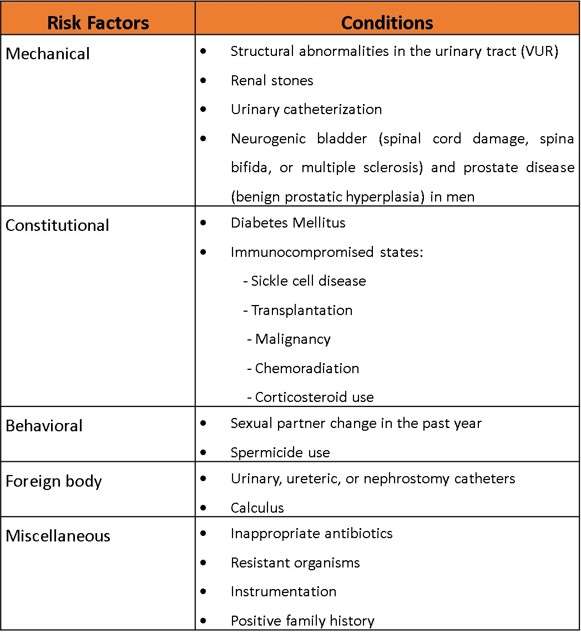

Risk Factors

Signs and Symptoms of Pyelonephritis

Acute pyelonephritis

- High fever, accelerated heart rate, chills, nausea/vomiting, flank pain at the costovertebral angle on the affected side, headache, and muscle pain.

- Pain (radiates toward the epigastrium) and may be colicky (in case of calculi or a sloughed kidney papilla infection)

- Dysuria, frequency, and urgency

- Cloudy, bloody, foul-smelling urine and increased WBCs and casts

- On physical examination tenderness at the costovertebral angle on the affected side.

Chronic pyelonephritis

- Usually, asymptomatic

- Signs of infection (fever, headache, weight loss, malaise, decreased appetite), lower urinary tract symptoms, and hematuria

- Polyuria and excessive thirst

- Persistent and recurring infection

- Flank or abdominal pain, fever unknown of origin

- In addition, inflammatory-related proteins can build up in organs and result in the disease AA amyloidosis.

Pathophysiology

- When bacteria enter the renal pelvis via ascending infection, traumas, and blood-borne infection, an inflammatory response occurs and increases in white blood cells.

- It is characterized by inflammatory foci that are interspersed throughout the renal interstitium. Small abscesses may form on the surface of the kidney. Scar tissue eventually takes the place of the lesions.

- In acute pyelonephritis, there is an acute suppurative inflammation of renal tubulointerstitial tissues. It is usually abrupt with chills, fever, headache, back pain, and tenderness.

- Similarly, chronic pyelonephritis is both chronic and progressive. There is scarring and deformation of the renal calyces and pelvis due to the persistent and securing infection.

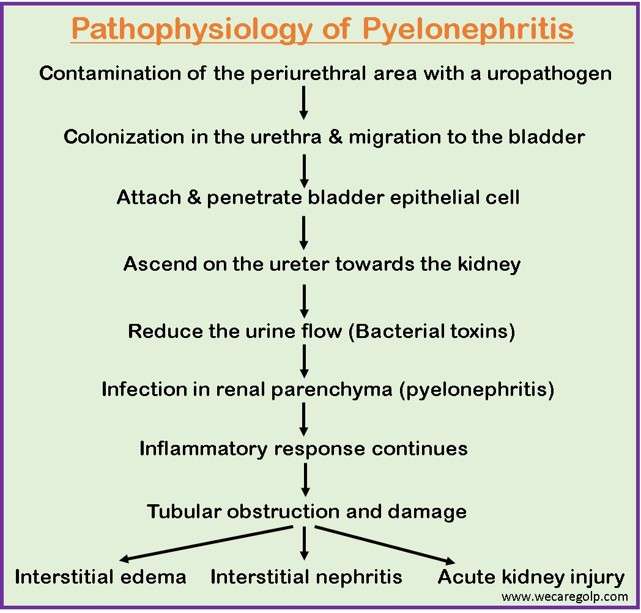

- The periurethral area contaminates with a uropathogen.

- The pathogen colonizes the urethra and migrates to the bladder.

- Fimbria allows it to attach and penetrate the bladder epithelial cell. Following penetration, bacteria continue and may form biofilms.

- After sufficient bacterial colonization, bacteria may ascend on the ureter towards the kidney. Fimbria may aid in the ascension process. Bacterial toxins may also play a role by inhibiting peristalsis (reducing the urine flow).

- The infection in renal parenchyma results in an inflammatory response. While infection of the renal parenchyma is usually the result of bacterial ascension, this can also occur from hematogenous spread.

- If this cascade of inflammatory response continues, tubular obstruction and damage occur, leading to interstitial edema. Further, it can also lead to interstitial nephritis, causing acute kidney injury.

Diagnosis

Urinalysis

- Urine dipstick testing, microscopic urinalysis, or both are commonly used in diagnosing UTIs, including pyelonephritis.

- In the majority of cases of acute pyelonephritis in women, there is significant pyuria or a positive leukocyte esterase test, which is frequently followed by proteinuria, microscopic hematuria, or a positive heme dipstick test.

- Although white cell casts can be seen in other situations, they are unique to acute pyelonephritis, along with other symptoms of UTI.

- Urine cultures are positive in 90% of patients with acute pyelonephritis, and culture specimens should be collected before starting antibiotics. The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) defines pyelonephritis as a urine culture having at least 10,000 colony-forming units (CFU) per mm3 and symptoms consistent with the diagnosis. Urine specimens are typically collected using a midstream clean-catch approach.

- Gram stain examination of urine can help in the selection of early antibiotic treatment in some difficult patients. Another possibility is to employ the antibody-coated bacteria test, which may aid in the localization of asymptomatic upper UTIs.

Blood Test

- A complete blood count (CBC) for white blood cells and a complete metabolic panel to assess renal function (BUN and creatinine) can be performed.

- Patients who are in the hospital should get blood cultures; Up to 20% of these people get positive results.

Imaging

- Typically, imaging techniques involve ultrasonography, helical CT, or intravenous urography (IVU).

- On imaging, the hallmark of chronic pyelonephritis (typically with reflux or obstruction) is a broad, deep, segmental, coarse cortical scar that generally extends to one or more of the renal calyces.

Management

Acute pyelonephritis

- Ambulatory patients presenting with simple acute pyelonephritis may be eligible for outpatient treatment. They must be in otherwise good health and not pregnant.

- They must also be treated in the emergency department (ED) with IV or oral fluids, antipyretic pain medicine, and dosage of parenteral antibiotics.

- Patients with acute uncomplicated pyelonephritis are often managed as outpatients if they are not dehydrated, do not have nausea or vomiting, and do not have signs or symptoms of sepsis.

- Other patients, including all pregnant women, may be admitted to the hospital for at least two or three days of parenteral treatment. Once the patient is afebrile and clinically improving, oral medicines may be replaced.

- Emergency surgery may be necessary for a patient who has a fever or positive blood culture findings that last more than 48 hours, in a patient whose health worsens, or in a patient who seems toxic for more than 72 hours.

- These individuals might be suffering from an abscess or obstructive calculus. Antibiotics following urine culture and sensitivity offer oral antibiotic treatment for 10-14 days in acute pyelonephritis. In extreme cases of acute pyelonephritis, an antibiotic may be given intravenously.

- Analgesics (NSAIDs or opioids) are prescribed

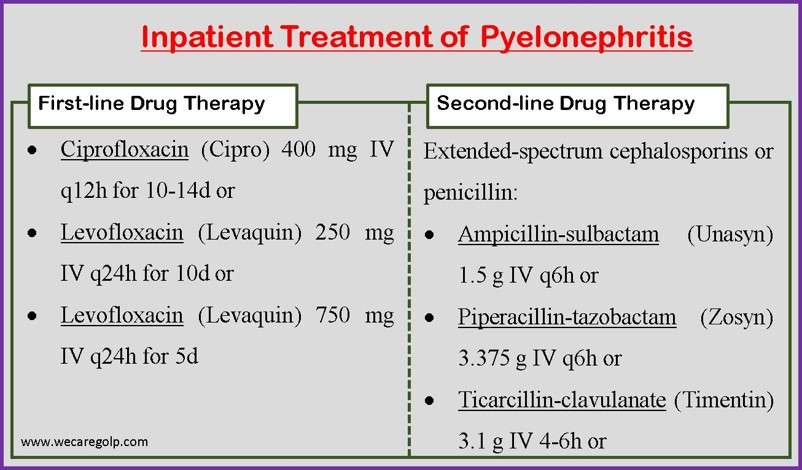

INPATIENT TREATMENT

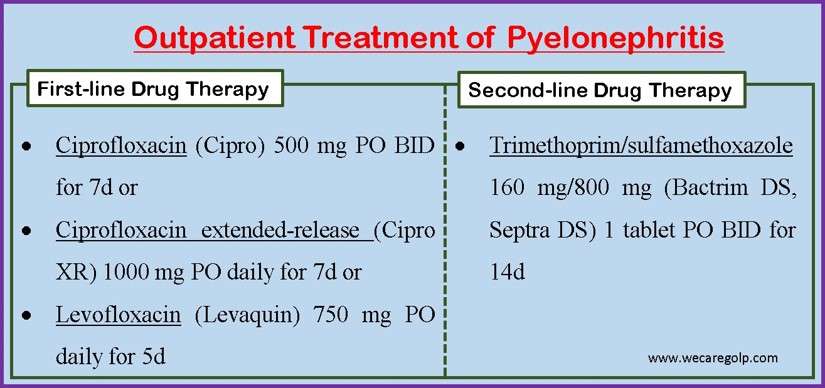

OUTPATIENT TREATMENT

If fluoroquinolone resistance is estimated to be greater than 10%, provide a single 1g IV dosage of ceftriaxone (Rocephin) or a consolidated 24-hour dose of an aminoglycoside (gentamicin 7 mg/kg IV, tobramycin 7 mg/kg IV, or amikacin 20 mg/kg IV).

Chronic Pyelonephritis

- Antibiotics same as in an acute case

- Do not give high fluid intake (if renal failure is significant)

- Control hypertension through reduction of dietary sodium, pharmacologic therapy- antihypertensive drugs

Complications

Acute pyelonephritis

- Renal or perinephric abscess formation

- Sepsis

- Renal vein thrombosis

- Papillary necrosis

- Acute renal failure

- Emphysematous pyelonephritis (EPN)

Chronic pyelonephritis

- Proteinuria

- Focal glomerulosclerosis

- Progressive renal scarring leading to end-stage renal disease

- Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis – May occur in approximately 8.2% of cases and 25% of patients with pyonephrosis

- Pyonephrosis – May occur in obstruction cases

- Progressive renal scarring (reflux nephropathy)

Prevention

- Pyelonephritis prevention is recognizing clinical circumstances that may contribute to the disease and devising a plan to reduce the chance. These measures may involve

- Changing one’s contraceptive habits

- Using prophylactic antibiotics,

- Detecting and treating cystitis early.

- If these techniques do not remove the infection, or there is a recurrence of infection, or relapse (reinfection within 14 days of finishing an adequate regimen), the patient must be evaluated for predisposition anatomic, functional, or structural problems.

- One of the greatest strategies for healthy, young, premenopausal women to avoid acute pyelonephritis is to focus on preventing one of the more prevalent predisposing factors, urinary tract infections.

- While numerous variables can contribute to urinary tract infections, simple strategies help avoid germs from entering the urethra and climbing structures.

- Urinate before and shortly after intercourse

- Wipe from front to back after peeing and defecating.

- Aside from behavioral therapies, the following can also prevent UTIs.

- Cranberry juice

- Probiotics

- Low-dose prophylactic antibiotics

- Patients must finish the whole course of medicines and take them as advised to avoid recurring acute pyelonephritis. Preventing dehydration also aids in the prevention of acute pyelonephritis and improves kidney function.

Prognosis

- Prompt diagnosis and therapy are critical in individuals with acute pyelonephritis. Any delay in treatment can frequently result in severe morbidity. Delays in effective care can result in extended hospital stays, significant pain, and disability.

- The majority of pyelonephritis episodes are simple and curable. Prognosis varies based on the kind of pyelonephritis and the time and length of therapy. The mortality rate for UTI ranges from 5% to 33%. The mortality rate for acute pyelonephritis is 10-20%.

- The prognosis of chronic pyelonephritis varies greatly, although the disease usually advances slowly. For the first 20 years after diagnosis, the majority of patients have sufficient renal function.

- Although managed, frequent exacerbations of acute pyelonephritis frequently worsen kidney shape and function. Continued blockage predisposes to or maintains pyelonephritis and raises intrapelvic pressure, both of which directly harm the kidney.

Summary

- Pyelonephritis is a kidney infection. The majority of instances of pyelonephritis are caused by the ascent of bacterial infections from the bladder to the kidney (mainly gram-negative bacilli, but rarely gram-positive organisms such as Enterococcus species).

- Patients with urinary tract abnormalities (particularly children with VUR) are more likely to get this illness. Pregnancy and kidney transplantation both raise the risk of it.

- Patients who have a bloodstream infection with a pathogen such as Staphylococcus aureus or Candida species are at risk of hematogenous seeding of the kidneys.

- Patients complain of flank discomfort and fever. Urinary symptoms such as dysuria, urgency, or frequency are frequently related. Gross hematuria may occur in rare cases. Urinalysis helps to diagnose it. The course of antibiotic therapy is the treatment choice.

References

- Belyayeva, M., & Jeong, J. M. (2022, Sep 18). Acute pyelonephritis. StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved 2022, Dec 30 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519537/#article-28095.s2

- Brown, P., Ki, M., & Foxman, B. (2005). Acute pyelonephritis among adults. Pharmacoeconomics, 23, 1123-1142. Retrieved 2022, Dec 30 from https://link.springer.com/article/10.2165/00019053-200523110-00005

- Buonaiuto, V. A., Marquez, I., De Toro, I., Joya, C., Ruiz-Mesa, J. D., Seara, R., Plata, A., Sobrino, B., Palop, B., & Colmenero, J. D. (2014, Dec 10). Clinical and epidemiological features and prognosis of complicated pyelonephritis: a prospective observational single hospital-based study. BMC infectious diseases, 14(1), 1-8. DOI: 10.1186/s12879-014-0639-4

- Choong, F. X., Antypas, H., & Richter-Dahlfors, A. (2015, Oct). Integrated Pathophysiology of Pyelonephritis. Microbiology Spectrum, 3(5), 3-5. DOI: 10.1128/microbiolspec.UTI-0014-2012

- Drai, J., Bessede, T., & Patard, J. J. (2012, Nov). Management of acute pyelonephritis. Progres en Urologie: Journal de L’association Francaise D’urologie et de la Societe Francaise D’urologie, 22(14), 871-875. DOI: 10.1016/j.purol.2012.06.002

- Neguse, S. (2020, Sep). Pyelonephritis. Journal of the American Academy of PAs, 33(9), 48-49. DOI: 10.1097/01.JAA.0000694984.12178.73

- Raszka Jr, W. V., & Khan, O. (2005, Oct). Pyelonephritis. Pediatrics in review, 26(10), 364-370. DOI: 10.1542/pir.26-10-364

- Roberts, J. A. (1999, Nov). Management of pyelonephritis and upper urinary tract infections. Urologic Clinics of North America, 26(4), 753-763. DOI: 10.1016/s0094-0143(05)70216-0

- Venkatesh, L., & Hanumegowda, R. K. (2017, Jun). Acute pyelonephritis-correlation of clinical parameter with radiological imaging abnormalities. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research: JCDR, 11(6), TC15-TC18. DOI: 10.7860/JCDR/2017/27247.10033