Introduction

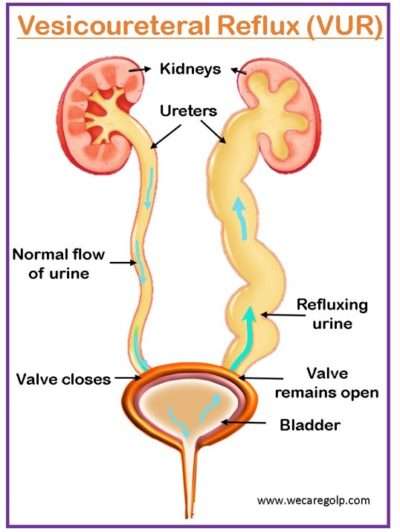

The retrograde flow of urine (regurgitation) from the urinary bladder to the upper urinary tract (kidney collecting system) is known as vesicoureteral reflux (VUR).

- Urine typically passes from the kidneys to the bladder via the ureters. When there is VUR (retrograde), the urine flow is in the opposite direction.

- Most of the time, it is caused by a primary maturation aberration of the vesicoureteral junction or a short distal ureteric submucosal tunnel in the bladder, which changes the function of the valve mechanism.

- VUR can occur alone or in conjunction with other congenital defects such as posterior urethral valves or full urinary tract duplication.

- It is the outcome of various irregularities relating to the ureter’s functional integrity, bladder dynamics, and the anatomic makeup of the ureterovesical junction (UVJ).

- The clinical importance of VUR assumes that VUR predisposes individuals to acute pyelonephritis by transferring germs from the bladder to the kidney, which can result in kidney scarring, hypertension, and chronic kidney disease (CKD).

Incidence

- VUR affects more than 10% of the population. VUR affects 17.2-18.5% of children who do not have urinary tract infections (UTIs), although it can affect up to 70% of those who do.

- Because of the greater length of the submucosal ureters, younger children are more vulnerable to VUR. This vulnerability reduces with maturity as the ureters lengthen as the children grow. 70% of children under the age of one who has a UTI have VUR. By the age of 12, this figure has dropped to 15%.

- Although VUR is more prevalent in males antenatally, there is a clear gender predominance in later life, with 85% of cases being female.

- VUR is more common in male neonates, although it appears to be 5-6 times more common in females over one year old than in boys.

- The incidence reduces with increasing patient age. VUR affects around 6% of adolescents and young people with end-stage renal failure (chronic renal insufficiency) who require treatment (dialysis or transplantation).

- VUR is the seventh leading cause of CRI in children.

Classification of Vesicoureteral Reflux

Primary VUR

- The most common kind of reflux is primary VUR, which is caused by an incompetent or insufficient closure of the ureterovesical junction (UVJ), which contains a portion of the ureter within the bladder wall (intravesical ureter).

- Normally, during bladder contraction, the intravesical ureter is entirely compressed and sealed off with the surrounding bladder muscles to avoid reflux.

- The failure of this anti-reflux mechanism in primary VUR is caused by a congenitally small intravesical ureter.

- This causes urine to flow backward in response to the normal increase in bladder pressure that occurs during the process of micturition.

- It may improve or even disappear during childhood because the ureters lengthen with the child’s growth.

- The intravesical ureter length may be genetically fixed, which might explain the greater prevalence in VUR patients’ families.

- Primary VUR has been linked to an increased risk of UTI and kidney scarring, often known as reflux nephropathy (RN).

Secondary VUR

- Secondary VUR, in contrast to primary VUR, is caused by a failure in the urinary system. Recurrent UTIs are frequently suggested as the etiological agents of secondary VUR.

- Several studies show that UTIs might cause the ureters to enlarge, resulting in urinary system blockage.

- The obstruction might be caused by an aberrant fold of tissue in the urethra that prevents urine from easily exiting the urinary bladder.

- Another reason for secondary VUR might be a nerve condition that prevents the bladder from stimulating it to discharge urine.

- Bilateral reflux is common in children with secondary VUR.

- It is a result of abnormally high pressure in the bladder that fails the closure of the UVJ during bladder contraction.

- Secondary VUR is often associated with anatomic or functional bladder obstruction,

Causes of Vesicoureteral Reflux

Primary VUR

Lack of maturation of the vesicoureteral junction (VUJ)

- Insufficient submucosal length of the ureter

- Alterations of the ureteral wall

Congenital anomalies of the VUJ

- Ectopic superolateral position of the lower pole ureter

- Perpendicular ureteric insertion of the bladder (golf-hole ureteric orifice)

- Absence of adequate detrusor backing

Secondary VUR

Organic causes

- Pyeloureteral duplicity

- Paraureteral or hutch diverticula

- Posterior urethral valves

- Urethral or meatal stenosis

Dysfunctional disorders

- Neurogenic bladder

- Detrusor instability

- Cystitis or UTI

Signs and Symptoms of Vesicoureteral Reflux

VUR is asymptomatic unless it has led to a renal infection (febrile UTI).

In neonate

- Respiratory distress

- Failure to thrive

- Flank masses

- Urinary ascites

- Irritability

- Persistent high fever

- Listlessness

Infants and young children

- Pyrexia

- Dysuria

- Frequent urination

- Malodorous urine

- Gastrointestinal tract symptoms (when UTI is present as the initial presentation of VUR)

In adult

VUR may be asymptomatic in its mild cases, but it causes recurrent cystitis or pyelonephritis in 50-70% of patients.

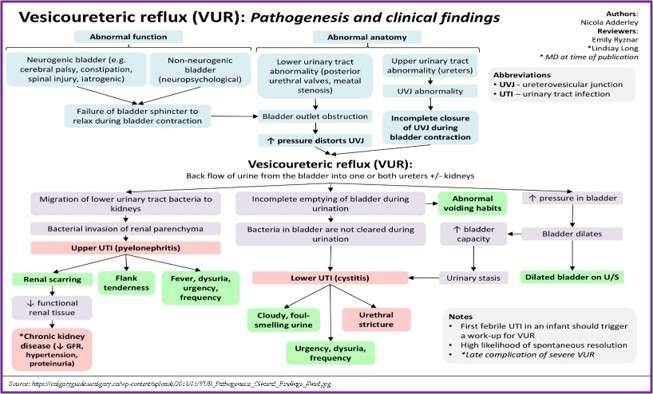

Pathophysiology of Vesicoureteral Reflux

- A malfunctioning flap-valve mechanism and VUR result from an abnormal intramural tunnel (e.g., a short tunnel). Urine tends to reflux up the ureter and into the collecting system when the intramural tunnel length is short.

- Due to neurogenic bladder and neuropsychological causes, there is a failure of the bladder sphincter to relax during bladder contraction which can result in the obstruction of the bladder.

- Lower urinary tract abnormalities like meatal stenosis or posterior urethral valves can also cause bladder outlet obstruction.

- This obstruction increases the pressure which in turn distorts UVJ. Upper urinary tract abnormality causes UVJ abnormality, this can result in incomplete closure of UVJ during bladder contraction.

- Both factors (increased pressure in the bladder distorting UVJ and incomplete closure of UVJ) result in the backflow of urine from the bladder into the ureters/kidneys (VUR).

- Infected urine and sterile urine can both enter the renal papillae. The renal damage appears to be caused predominantly by intrarenal reflux of contaminated urine.

- Bacterial endotoxins (lipopolysaccharides) trigger the host’s immunological response and cause the generation of oxygen-free radicals.

- During the healing phase, the release of oxygen-free radicals and proteolytic enzymes causes fibrosis and scarring of the damaged renal parenchyma.

- Higher grades of reflux are associated with renal lesions. Pyelonephritic scarring may produce significant hypertension over time owing to renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system activation.

- VUR scarring is one of the most prevalent causes of childhood hypertension.

- Lower UTI can also be associated with VUR, where clinical presentations like cloudy, foul-smelling urine, urgency., dysuria, and frequency can be present.

Diagnosis of Vesicoureteral Reflux

Laboratoy Tests

There are no laboratory diagnostic tests to diagnose VUR. To assess for complications, the following tests may be performed.

- Renal dysfunction as assessed by BUN and creatinine

- Urinalysis with culture UTI

Imaging Studies

VUR can be diagnosed using the following procedures:

- Nuclear cystogram/Radionuclide cystogram (RNC)

- Fluoroscopic voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG)

- Renal bladder Ultrasound (RBUS)

- DMSA (Dimercaptosuccinic Acid) Scan

Radionuclide Cystogram (RNC)

- A radionuclide cystogram (RNC) is a diagnostic imaging procedure used to detect ureteral and bladder abnormalities. A radiopharmaceutical substance is used in this treatment to scan the ureters and bladder.

- RNC can be conducted through retrograde instillation of the radiopharmaceutical directly into the bladder via a catheter or intravenously, permitting excretion into the urine collecting system by the kidneys.

- Images are obtained by detecting photons released by the radiopharmaceutical using a gamma camera.

- RNC is most usually used to identify VUR, which, if left untreated, can cause renal damage such as chronic renal failure, recurrent infections, and hypertension.

Fluoroscopic Voiding Cystourethrogram (VCUG)

The VCUG test is the gold standard for determining VUR. This test detects reflux easily, but it is difficult to determine which group of patients will have adverse sequelae of their condition, such as renal scarring. As a result, if patients with VUR depend solely on VCUG, they will be susceptible to the morbidity of monitoring and perhaps over-treatment.

- It is a lower urinary tract fluoroscopic investigation in which contrast is injected into the bladder through a catheter. The goal of the examination is to evaluate the bladder, urethra, postoperative anatomy, and micturition to detect the presence or absence of bladder and urethral anomalies, such as VUR.

- The major diagnostic technique for identifying VUR is VCUG. VUR is graded based on radiographic appearance by VCUG.

- The VCUG findings can be influenced by

- The size, type, and location of the catheter

- The pace of bladder filling

- The height of the column of contrast media

- The patient’s state of hydration

- The volume, temperature, and concentration of the contrast medium.

Grading

VUR grading categorizes VUR based on the height of reflux up the ureters and the degree of ureter dilatation:

- Grade I – Reflux just fills the ureter without dilatation.

- Grade II – Reflux into the renal pelvis and calyces without dilatation

- Grade III – Reflux fills and mildly dilates the ureter and collecting system, resulting in mild calyces blunting.

- Grade IV – Dilatation of renal pelvis and calyces with moderate ureteral tortuosity

- Grade V – Significant ureteral, pelvic, and calyceal dilatation; ureteral tortuosity; papillary impressions

Almost 85% of grade I and II VUR cases will resolve spontaneously. Approximately half of grade III cases and a smaller percentage of higher-grade cases will resolve spontaneously.

Renal Bladder Ultrasoung (RBUS)

- In addition to the voiding cystourethrogram, routine ultrasonography is routinely done to check the renal parenchyma for indications of scarring or anatomic abnormalities. Furthermore, by examining the distal ureters during bladder filling with micro-bubbles, ultrasonography has been examined as an alternative to standard fluoroscopic VCUG.

- Recent research suggests that contrast-enhanced voiding urosonography (ceVUS) detects VUR as well as traditional VCUG but without the radiation exposure of the latter.

- The most frequent first intervention for a child with a febrile or afebrile UTI is RBUS. It does not require ionizing radiation and is often well tolerated due to its painless and noninvasive nature.

- It may swiftly and comprehensively demonstrate urinary tract anatomy. However, many infants with congenital urinary tract anomalies are now diagnosed via prenatal ultrasounds and treated medically or surgically before a Febrile UTI occurs.

- RBUS is frequently seen as an essential component of urologic consultation or monitoring; nevertheless, for infants receiving rigorous prenatal care, it may provide just a small benefit. For VUR, RBUS has a sensitivity and specificity of 40% and 76%, respectively.

Dimercaptosuccinic Acid (DMSA) Scan

- The intravenous urogram has been replaced by DMSA as the gold standard for assessing kidney damage and persisting renal scarring.

- A normal DMSA scan will eliminate the necessity for a VCUG. This will isolate the most vulnerable VUR population and decrease the need for extensive VCUG testing.

- This viewpoint emphasizes renal parenchymal involvement rather than VUR as the cause of cumulative damage.

- Following DMSA scans, fresh scars are visible in the areas of past inflammation.

Management of Vesicoureteral Reflux

The European Association of Urology guidelines recommends both conservative and surgical treatment for VUR. Conservative treatment consists of the following steps to prevent febrile UTI:

- Watchful waiting

- Antibiotic prophylaxis, either intermittent or continuous

- Bladder rehabilitation in lower urinary tract dysfunction (LUTD) patients

- Consideration of circumcision in early childhood

- Imaging investigations should be performed regularly (e.g., VCUG, nuclear cystography, or DMSA scan)

Active Surveillance

- Medical care is not necessary in children with Grade I-III VUR because the majority of cases resolve spontaneously.

- In individuals with Grade IV VUR, a pharmacological treatment trial is recommended, especially in younger patients or those with unilateral illness.

- Only infants with Grade V are medically treated before surgery is recommended; for older patients, surgery is the only choice.

Antibiotic Therapy

The following recommendations are made for the initial management of VUR in infants under 1 year old:

- If a child has a history of a febrile UTI, continuous antibiotic prophylaxis (CAP) is advised.

- If a child has not had a history of febrile UTI, suggest CAP for grades III–V.

- If the child has never had a febrile UTI, consider CAP for VUR grades I–II.

The following recommendations are done for the initial management of VUR in children older than one year:

- Due to the elevated risk of UTI when bladder/bowel dysfunction (BBD) is present and being treated, CAP should be given to children who have both VUR and BBD.

- In the absence of BBD, CAP may be taken into account for the child with a history of UTIs.

- In the absence of BBD, recurrent febrile UTIs, or renal cortical abnormalities, observational care without CAP with the immediate beginning of antibiotic therapy for UTIs may be taken into consideration for the child with VUR.

- VUR can be treated surgically using both open and endoscopic techniques.

CAP drugs

Prophylaxis with low-dose antibiotics is the choice of the drug until the resolution of VUR. Every night, antibiotics are given at a half-normal dose.

- Amoxicillin or ampicillin infants younger than 6 weeks.

- Trimethoprim-Sulfamethoxazole (co-trimoxazole) – 6 weeks to 2 months

The following antibiotics are appropriate after two months:

- Nitrofurantoin Adult dosing 5-10 mg/kg/d PO. Dosing in children >3 months is 1-2 mg/kg/d PO hs

- Nalidixic acid

- Bactrim

- Trimethoprim

- Cephalosporins

Anticholinergic drugs

These drugs are bladder relaxants that regulate detrusor overactivity, which is a major secondary cause of VUR. Secondary causes of reflux caused by poor bladder compliance can be efficiently addressed with anticholinergic medications when used correctly.

Oxybutynin

- Adult dose:

- Oxybutynin: 5 mg PO bid/tid

- Oxybutynin extended-release (Ditropan XL) is 5-30 mg PO OD

- Pediatric dose: 1-5 mg PO BD/TDS

Surgical Management

Indications for surgery

Relative indications

- Reflux grades IV and V

- Despite medical treatment, reflux persists (beyond three years)

- Breakthrough UTIs in patients being treated with antibiotics prophylaxis

- Renal growth failure

- Multiple drug allergies that prevent prophylactic usage

- A desire to discontinue antibiotic prophylaxis (either by the doctor or by the patient/parents)

- Noncompliance with medical treatment.

Absolute indications

- Sudden Pyelonephritis

- Progressive renal scarring in antibiotic-treated individuals

- Antibiotics resistance

- A UVJ abnormalities

Surgical procedures

Ureteral reimplantation

- Ureteral reimplantation or ureteroneocystostomy is the most effective surgery to repair primary reflux, particularly in the presence of anatomic abnormalities.

- The surgical principle is extending the path of the intravesical ureter through a detrusor and/or submucosal tunnel to create an anti-reflux valve, providing good detrusor muscle backing, avoiding ureteric kinking, and creating a tunnel in the fixed area of the bladder.

- In general, ureteric reimplantation can be accomplished by an intravesical or extravesical method, or through a mix of both.

- The common objective of these procedures is to avoid VUR by establishing a functional flap-valve mechanism at the UVJ.

- Intravesical ureteroneocystostomy by Politano and Leadbetter is still one of the most often utilized techniques. Intravesical ureteroneocystostomy allows for the creation of a lengthy submucosal tunnel while preserving the anatomical location of the ureteric orifices for retrograde catheterization.

- Lich and Gregoir described the extravesical ureteral reimplantation procedure. The ureters are dissected to the UVJ. The detrusor is incised laterally following the normal route of the ureter, while the mucosa and trigonal attachments to the ureter are preserved. Closing the detrusor above the ureter creates a lengthy submucosal tunnel.

- The extravesical method eliminates the need for bladder opening and has been shown to lower the incidence of hematuria, bladder spasms, and convalescence. It also allows for the reimplantation of grossly dilated megaureters without tailoring.

Endoscopic Treatment

- Endoscopic treatment entails injecting a bulking agent submucosally into the bladder wall below the ureteral orifice or into the ureteral tunnel to increase tissue.

- It is a minimally invasive technique with a high likelihood of curing with just one operation. The injectable drug used is critical to the effectiveness of endoscopic therapy.

- The optimal injectable agent should be biocompatible to ensure safety and long-term effectiveness.

- The incidence of new renal scarring is highest in newborns and young children under the age of five. As a result, the bolus formed with an injectable agent should last at least five years.

- NASHA/Dx gel, which contains dextranomer microspheres in a non-animal hyaluronic acid-based gel, was created particularly for endoscopic therapy.

- The bulking agent raises the ureteral aperture and distal ureter, narrowing the lumen and limiting urine regurgitation up the ureter while permitting antegrade flow.

Complications of Vesicoureteral Reflux

- Hydronephrosis

- Pyelonephritis

- Obstructive nephropathy

- Reflux nephropathy

- Renal scarring

- Renal failure

- Hypertension

- Urosepsis

- Perinephric abscess

- Persistent, transient, contralateral reflux

- Postoperative ureteral obstruction

Prevention

- Usually, primary VUR treats with low-dose long-term antibiotics to prevent UTIs and avoid surgery.

- There are no definitive preventive measures for VUR. But the following measures can reduce the progression of the disease.

- Drinking plenty of water

- Immediate diaper change

- Encourage children to urinate regularly

- Treatment for constipation, urinary/fecal incontinence

- A balanced diet with plenty of high-fiber foods

- Limit intake of processed sugar

Prognosis

- Most cases of VUR will recover spontaneously. 20% to 30% will have further infections, but only a few will have long-term renal sequelae.

- It is impossible to determine whether scarring will occur once the VUR has been detected. Scarring is more likely in younger children when suitable therapy modalities are not identified.

- Factors that improve the chance of a successful resolution include lower severity of reflux, age of diagnosis less than 2 years, and unilateral disease.

Summary

- The retrograde urine flow from the bladder into the ureter is known as VUR. The most frequent kind of VUR is primary VUR, which is caused by a congenital abnormality in the terminal section of the ureter.

- Secondary VUR can be caused by bladder outlet blockage, cystitis, and congenital ureteral defects (e.g., ureteral duplication, ectopic ureter).

- VUR in children is frequently asymptomatic until they develop a UTI (presenting with fever, dysuria, urgency, and flank pain).

- In severe cases of reflux nephropathy, further symptoms include hypertension, uremia, and renal failure.

- The initial examination for VUR comprises laboratory testing (creatinine levels, electrolytes) and renal ultrasound to assess kidney function and any structural damage.

- The VCUG is the preferred diagnostic test for imaging urine reflux and its severity.

- Most cases of primary VUR resolve on their own as the child grows older.

- Prophylactic antibiotics (e.g., trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, nitrofurantoin) and behavioral adjustment (timed micturition) are effective in treating and avoiding problems.

- Patients with greater degrees of primary VUR, ureteral dilatation, hydronephrosis, or recurring UTIs require endoscopic/surgical vesicoureteral junction repair.

References

- Banker, H., Aeddula, N.R. (2022, Jan). Vesicoureteral reflux. StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved 2023, Jan 19 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK563262/

- Baskin, L.S. (2022, May 11). Congenital ureteropelvic junction obstruction. UpToDate. Retrieved 2023, Jan 19 from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/congenital-ureteropelvic-junction-obstruction

- Estrada, CR. (2021, September 30). Vesicoureteral Reflux. Medscape. Retrieved 2023, Jan 18 from https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/439403-overview

- Hajiyev, P., & Burgu, B. (2017, April). Contemporary management of vesicoureteral reflux. European Urology Focus, 3(2-3), 181-188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euf.2017.08.012

- Heidenreich, A., Özgur, E., Becker, T., & Haupt, G. (2004). Surgical management of vesicoureteral reflux in pediatric patients. World journal of urology, 22(2), 96-106. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00345-004-0408-x

- Lahdes-Vasama, T., Niskanen, K., & Rönnholm, K. (2006, Sep). Outcome of kidneys in patients treated for vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) during childhood. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation, 21(9), 2491-2497. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfl216

- Mattoo, T.K., Greenfield, S.P. (2021, Mar 30). Clinical presentation, diagnosis, and course of primary vesicoureteral reflux. UpToDate. Retrieved 2023, Jan 19 from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-presentation-diagnosis-and-course-of-primary-vesicoureteral-reflux

- Nelson, CP. (2022, July 26). Pediatric Vesicoureteral Reflux. Medscape. Retrieved 2023, Jan 18 from https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1016439-overview

- Routh, J. C., Bogaert, G. A., Kaefer, M., Manzoni, G., Park, J. M., Retik, A. B., Rushton, H.G., Snodgrass, W.T., & Wilcox, D. T. (2012, April). Vesicoureteral reflux: current trends in diagnosis, screening, and treatment. European urology, 61(4), 773-782. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2012.01.002

- Tekgül, S., Riedmiller, H., Hoebeke, P., Kočvara, R., Nijman, R. J., Radmayr, C., Stein, R., & Dogan, H. S. (2012, Sep). EAU guidelines on vesicoureteral reflux in children. European urology, 62(3), 534-542. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2012.05.059

- Venhola, M., & Uhari, M. (2009). Vesicoureteral reflux, a benign condition. Pediatric nephrology, 24(2), 223-226. Doi: 10.1007/s00467-008-0912-0

- Williams, G., Fletcher, J. T., Alexander, S. I., & Craig, J. C. (2008). Vesicoureteral reflux. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, 19(5), 847-862. Doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007020245