Introduction

Septic shock is a serious medical condition that occurs as a severe complication of an infection. It is the most common type of circulatory shock. It is thought to be a progression of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) with a significant rise in mortality due to severe circulatory abnormalities.

These patients are frequently referred to be the “sickest patients in the hospital,” as healthcare professionals work to save them from long-term consequences or death.

It is a type of distributive shock characterized by an uneven distribution of blood flow in the smallest blood capillaries, which leads to the insufficient blood supply to body tissues, resulting in ischemic and organ dysfunction. It does not respond to IV fluid infusions for resuscitation and needs inotropic or vasopressor drugs to keep systolic blood pressure stable. If an organism cannot fight off an infection, a systemic reaction can occur, leading to severe sepsis, septic shock, organ damage, or even death. When an organism fails to fight off an infection, a systemic response can occur, leading to severe sepsis, septic shock, organ damage, and even death.

Click for the medical terms.

Incidence

- Worldwide, there is a sepsis incidence of more than 20 million cases per annum. Among them, septic shock-related death can be as high as 50%, even in developed countries.

- According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), it is the most common cause of death in ICUs and the 13th top cause of death in the US. According to the Global Burden of Disease Study, sepsis, including severe sepsis and septic shock, is estimated to have caused 19.7 million cases and 5.3 million deaths worldwide in 2017.

- In developed countries, it is often associated with healthcare-associated infections and is more prevalent in intensive care units (ICUs) and hospital settings. However, with advancements in healthcare practices, the incidence and mortality rates have been decreasing in recent years.

Causes of Septic Shock

Bacteria

- Gram-positive and gram-negative bacterial infections are the most common cause of septic shock.

- Some responsible bacteria are:

- Staphylococcus aureus

- Pseudomonas

- Escherichia coli

- Acinetobacter

- Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA)

- Vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE)

- The most common bacterial-causing infections leading to septic shock are:

- Bacteremia (bloodstream infections)

- Skin and soft tissue infections

- Intra-abdominal infections like appendicitis, pancreatitis

- Pneumonia

- Pyelonephritis

- Urinary tract infections (UTIs)

Viruses

- Viral infections are less common than bacterial ones.

- Viruses can seriously inflame the body and damage various organs which may include

- Influenza

- Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)

- Herpes simplex virus (HSV)

Fungi

- It could result from invasive fungal infections.

- Fungal septic shock usually affects those with

- Weakened immune systems

- Undergoing immunosuppressive therapy

- Frequently associated fungi are

- Candida

- Aspergillus species

Parasites

- It is relatively rare.

- Examples of parasitic infections that may cause septic shock include

- Severe malaria

- Disseminated strongyloidiasis

Stages of Sepsis

A person may have sepsis in phases that progress from mild to severe to septic shock.

It can be characterized by three stages:

Sepsis

It is an infection-related systemic reaction. In this stage, an infection causes the body to go into a state of systemic inflammation. Fever, an elevated heart rate, fast breathing, and altered mental status are possible symptoms.

Severe sepsis

Severe sepsis results when sepsis causes organ malfunction. Evidence of organ dysfunction is present at this stage, which may show up as low blood pressure, decreased urine output, abnormal liver function tests, abnormal blood coagulation, or altered mental status.

Septic shock

This is the most serious stage, which is marked by persistently low blood pressure that does not improve with fluid resuscitation. It is linked to severe cellular, metabolic, and circulatory problems. There is a higher probability of multiple organ failure and more severe organ dysfunction.

Risk Factors of Septic Shock

- Children age under 10 (including neonates and infants)

- People over age 65

- Patients with

- Chronic illnesses like diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease (CKD), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

- Anemia

- Cirrhosis

- Cancer

- Immunocompromised patient, e.g., receiving chemotherapy and HIV

- Leucopenia, particularly when connected with cancer or cytotoxic drug therapy

- Prolonged hospitalization patients, particularly in the intensive care unit (ICU)

- Use of immunosuppressive agents like corticosteroids

- Treatment with antibiotics in the last 90 days

- Poor surgical technique, major surgeries, trauma, and extensive burns

- Presence of indwelling devices such as vascular or urinary catheters, endotracheal or drainage tubes, and other foreign objects

Signs and Symptoms of Septic Shock

Early stages (compensated)

The early stage of septic shock is not associated with hypovolemia. It is also called warm shock.

- Tachycardia (heart rate of more than 90 beats per minute)

- Fever (temperature higher than 38˚C) or hypothermia (temperature less than 36˚C)

- Tachypnea (respiratory rate of more than 20 breaths per minute)

- Warm extremities

- Shivering and malaise

- Wide pulse pressure

Late stage (decompensated)

The decompensated or late stage is associated with hypovolemia with superimposed sepsis. It is also called cold shock.

- Hypotension

- Cold extremities

- Cold clammy skin

- Bradycardia (slow heart rate, less than 60 beats per minute)

- Hypothermia

- Hypoxia (decreased tissue perfusion)

- Oliguria/anuria

- Cyanosis

- Jaundice

- Altered mental status

- Ileus (absent bowel sounds)

Last stage (irreversible)

- Continued hypoxia and persistent hypotension despite sufficient fluid resuscitation, requiring vasopressors

- Progressive rapidly into MODS

- Death

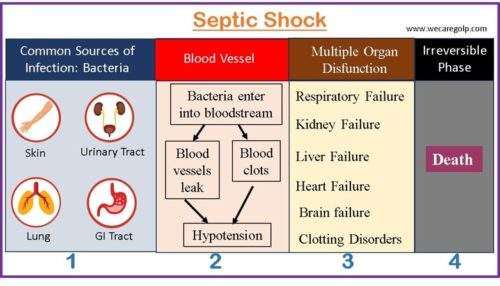

Pathophysiology of Septic Shock

Immune response: When microorganisms invade body tissues, it triggers the immune response. This response involves the activation of cytokines like tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin-1 (IL-1) and mediators like high-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) protein associated with inflammation. Immune cells such as monocytes, macrophages, and dendrite cells secrete TNF- α, IL-1, and HMGB1.

Inflammatory response: The inflammatory response leads to increased capillary permeability, causing fluid to seep from the capillaries. This disrupts tissue perfusion and impairs the delivery of oxygen and nutrients to cells.

Coagulation system activation: Inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines released during the response activate the coagulation system. This can lead to the formation of clots and microvascular occlusions, further compromising tissue perfusion.

Physiological progression: The imbalance of the inflammatory response and the clotting and fibrinolysis cascades is considered critical in the progression of severe sepsis. Sepsis is an evolving process, and its clinical signs and symptoms may vary. In the early stage of septic shock, blood pressure may remain within normal limits or be hypotensive but responsive to fluids. Other symptoms include increased heart rate, hyperthermia, respiratory rate elevation, compromised GI status, altered mental status, increased serum glucose, insulin resistance, elevated lactate levels, and elevated inflammatory markers.

Organ dysfunction: As sepsis progresses, tissues become less perfused and acidotic, and signs of organ dysfunction become evident. Cardiovascular failure, unresponsive blood pressure, end-organ damage (such as acute kidney injury (AKI), pulmonary dysfunction, and hepatic dysfunction), and multiple organ dysfunction may occur.

Septic shock: In this phase, blood pressure drops, and the skin becomes cool, pale, and mottled. The temperature may be normal or below normal. Heart and respiratory rates remain rapid. Urine production ceases, and multiple organ dysfunction progresses, leading to death.

Diagnosis of Septic Shock

Clinical signs

The presence of two of the following four clinical signs:

- Fever (temperature higher than 38 C or hypothermia (temperature less than 36 C)

- Tachycardia (heart rate of more than 90 beats per minute),

- Tachypnea (respiratory rate of more than 20 breaths per minute)

- Leukocytosis: White blood cells (WBCs) greater than 12,000/cu mm) / leukopenia: WBCs less than 4,000/cu mm with or without bandemia (more than 10%).

Laboratory tests

- Hyperglycemia (blood glucose greater than 140 mg/dL in a patient without diabetes.

- Leukocytosis or leukopenia

- Bandemia (10% or more band cells (immature neutrophil))

- Elevated C-reactive protein (more than 50 mg/dL)

- Elevated procalcitonin (more than 2ևg/L)

- Increased serum creatinine (more than 1.4 mg/dL)

- Coagulation abnormalities (PTT: more than 60 secs; INR: more than 1.5)

- Thrombocytopenia (platelets below 100,000/mm3)

- Hyperbilirubinemia (total bilirubin more than 4 mg/dL)

- Hyperlactatemia (lactate above 2 mmol/L)

- PaO2: FiO2 less than 300

- Urinalysis

- Cultures

- Blood culture

- Urine culture

- Wound culture

- Tracheal culture (if intubated)

- Additional tests

- Liver function tests (LFT)

- Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) panel

- Arterial blood gas (ABG) analysis

Lumbar puncture

Lumbar puncture may be indicated in the suspicion of the following conditions.

- Encephalitis

- Meningitis

- Febrile pediatric patients under six weeks of age

Imaging tests

- The precise site of the infection will not always be visible in patients.

- To help locate the affected body parts, a physician may employ imaging tests like

- X-rays

- Computerized tomography (CT) scans

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans

- Ultrasounds

Management of Septic Shock

It is vital to remember that septic shock can advance quickly. Therefore, early detection, prompt intervention, and proper therapy are essential for improving outcomes. A timely and effective resuscitation is required. The patient should be admitted to ICU.

The aims of management are:

- Improve hemodynamic status

- Restore tissue perfusion

- Combat bacteria and cytokines

- Eliminate septic focus

The management of septic shock can be done in the following ways.

Fluid Resuscitation

- Initiate aggressive fluid resuscitation in patients with hypotension. The first fluid choice is crystalloids (normal saline or lactated Ringer’s solution). The amount of fluid resuscitation is calculated depending on the patient’s condition and vital signs to avoid fluid overload.

- Albumin administration can be helpful in case of a large amount of fluid infusion.

- Packed red blood cells can be transfused when hemoglobin is <7 g/dL.

Medications

- Start vasopressor agents if fluid resuscitation does not restore an effective BP. Vasopressors or vasoactive agents act as a vasoconstrictor and increase blood circulation to the organs.

- Administer norepinephrine centrally (first choice of drug).

- When a patient is in septic shock, epinephrine, phenylephrine, or vasopressin should not be given as the first vasopressor as they may cause further complications like tachycardia and arrhythmias. Therefore, these drugs may be added to norepinephrine if needed.

- Administer broad-spectrum antibiotics within the first hour. The type of antibiotics depends on the type of bacterial infection. Therefore, obtain first the result of blood, sputum, urine, and wound culture and treat accordingly. Culture should be obtained before antibiotic administration. A combination of antimicrobial therapy may be used to cover a wide range of potential causative organisms.

- Consider IV hydrocortisone therapy (corticosteroid) if the patient is not responding to fluid and medications.

Surgery

- Surgery may be needed to remove the source of the infection.

- Types of surgery can be

- Removal of dead or infected tissues

- Drainage of abscesses

- Change or removal of tubes, catheters, or other medical devices

Supportive Management

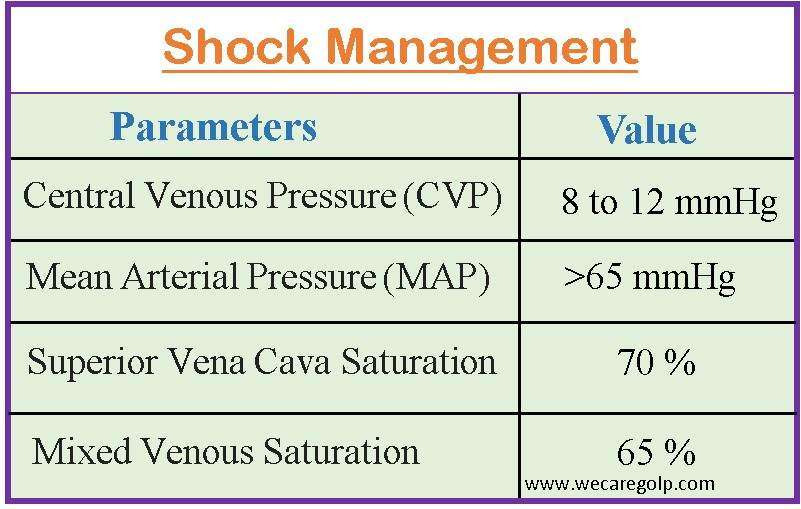

- Monitor some parameters (see in the table below) regularly for the effectiveness of shock management.

- Oxygen therapy and mechanical ventilation can support the respiratory system.

- Provide adequate IV sedation and analgesia; avoid using neuromuscular blockade agents when possible.

- Control serum glucose <180 mg/dL with IV insulin therapy.

- Implement interventions and medications to prevent deep vein thrombosis and stress ulcer prophylaxis.

- Discuss advance care planning with patients and families.

Complication of Septic Shock

Septic shock can lead to serious health conditions which may need to be treated urgently. If the complications are not treated timely, they can be fatal. The survival chance of a septic shock patient depends on the type of infection, the time of therapy begins, and the affected organs.

Complications can include:

- Respiratory failure

- Heart failure

- Kidney failure,

- Liver failure

- Injury

- Clotting abnormalities

- MODS

- Metabolic disturbances (hyperglycemia, metabolic acidosis, and electrolyte abnormalities)

- Long-term complications: Survivors may experience long-term physical, cognitive, and psychological effects. These can include muscle weakness, cognitive impairment, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, and depression.

Prevention of Septic Shock

The following steps can help lower the risk of septic shock:

- Vaccinate yourself frequently against viral illnesses that might lead to sepsis.

- Practice good hygiene.

- Care for any open or gaping wounds.

- Obey doctor recommendations for treating bacterial infections.

- Treat the infections promptly as symptoms appear.

- Control diabetes.

- Avoid smoking.

- Advice on hand washing properly who has weakened immune systems.

Prognosis

- Despite the high mortality rate associated with septic shock, improvements in critical care and sepsis therapy have increased survival rates.

- Early antibiotic administration, fluid resuscitation, source control, and supportive therapy have all improved results.

- However, there is still a high risk of death associated with some complications such as MODS, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and AKI.

- Survivors may face long-term physical, cognitive, and psychological effects that can impact their quality of life.

Summary

Septic shock is a life-threatening condition that occurs as a severe complication of infection. The characteristics of septic shock are a harmful inflammatory response, organ dysfunction, and dangerously low blood pressure. Prompt recognition and aggressive treatment are crucial for improving outcomes. The causative agents can be bacterial, viral, fungal, or parasitic infections. The early-stage symptoms include fever, rapid heart rate, and altered mental status, while the late stages show hypovolemia, cold skin, and organ failure.

Diagnosis involves laboratory tests and imaging scans. The management of septic shock should be done within the first six hours of diagnosis which includes fluid resuscitation, antibiotics, vasopressor support, and addressing the source of infection. Complications can be severe, and the prognosis depends on various factors. Prevention involves vaccinations, good hygiene, and prompt treatment of infections.

Read Also:

- CARDIOGENIC SHOCK (CS): CAUSES, SYMPTOMS, MANAGEMENT

- OXYGEN THERAPY: ENHANCING RESPIRATORY SUPPORT

- ABG ANALYSIS (ARTERIAL BLOOD GAS TEST)

References

- Prescott, H. C., & Angus, D. C. (2018). Enhancing recovery from sepsis: A review. JAMA, 319(1), 62-75. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.17687

- Rhee, C., Dantes, R., Epstein, L., et al. (2017). Incidence and trends of sepsis in US hospitals using clinical vs claims data, 2009-2014. JAMA, 318(13), 1241-1249. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.13836

- Felman, A. (2023, April 6). How to avoid septic shock. Medical News Today. Retrieved on 2023, June 5 from https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/311549

- Mayo Clinic. (2023, Feb 10). Sepsis Retrieved on 2023, June 5 from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/sepsis/symptoms-causes/syc-20351214

- Cleveland Clinic. (2022, June 14). Septic Shock. Retrieved on 2023, June 4 from https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/23255-septic-shock

- Silvestri, L. A., & Silvestri, S. A. (2023). Saunders Comprehensive Review for the NCLEX-RN Examination (9th ed.). Elsevier.

- Mandal, G. N. (2015). Textbook of Medical-Surgical Nursing. Makalu publication house.

- Cheever, K. H., & Hinkle. J. K. (2014). Brunner & Suddarth’s Textbook of Medical-Surgical Nursing. Lisa McAllister.