Introduction

Myasthenia gravis (MG) is an acquired, rare autoimmune disorder caused by antibody-and cell-mediated destruction of acetylcholine receptors and blockade of neuromuscular transmission that results in episodic skeletal muscle weakness and easy fatigability. The autoimmune attack occurs when autoantibodies are produced against the nicotinic acetylcholine postsynaptic receptor (neurotransmitter-gated ion channel) at the neuromuscular junction of skeletal muscle.

Incidence

- Both the incidence and prevalence of MG have been rising consistently and gradually over the world in the past decades.

- The incidence of MG in patients of 50 years or more increased by 1.5-fold, while the onset at age of 65 years or more showed a 2.3-fold rise.

- The overall global prevalence of MG is 12.4 people per 100,000 population.

Clinical Classification of Myasthenia Gravis

Classification according to the Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America (MGFA)

- Class I: Any ocular muscle weakness, possible ptosis with no other evidence of muscle weakness elsewhere in the body

- Class II: Mild weakness affecting other than ocular muscles; may also have ocular muscle weakness of any severity

- Class II a: Predominantly affecting limb, axial muscles, or both; may also have lesser involvement of oropharyngeal muscles.

- Class II b: Predominantly bulbar and/or respiratory muscles; may also have lesser or equal involvement of limb, axial muscles, or both.

- Class III: Moderate weakness affecting other than ocular muscles; may also have ocular muscle weakness of any severity

- Class III a: Predominantly affecting limb, axial muscles, or both; may also have lesser involvement of oropharyngeal muscles

- Class III b: Predominantly bulbar and/or respiratory muscles; may also have lesser or equal involvement of limb, axial muscles, or both

- Class IV: Severe weakness affecting other than ocular muscles; may also have ocular muscle weakness of any severity

- Class IV a: Predominantly affecting limb, axial muscles, or both; may also have lesser involvement of oro-pharyngeal muscles

- Class IV b: Predominantly bulbar and/or respiratory muscles; may also have lesser or equal involvement of limb, axial muscles, or both (Can also include feeding tube without intubation)

- Class V: Intubation with or without mechanical ventilation is needed to maintain the airway

Causes of Myasthenia Gravis

- Myasthenia gravis is an autoimmune disorder in which the body produces antibodies that prevent the muscle cells from receiving messages from the neuron.

- The disease is linked to tumors of the thymus in some cases.

Risk Factors of Myasthenia Gravis

- Women usually develop Myasthenia gravis in the decade of their 20s and Men between the decades of their 60s.

- People with certain genetic markers (HLA-B8, DR3) are more prone to develop the disease.

- Infants of mothers with the disease can develop neonatal MG which is a temporary condition that occurs because of the transmission of the mother’s antibodies. The abnormal maternal antibodies are usually washed out from the baby’s bloodstream within about two to three months, ending the baby’s symptoms of muscle weakness.

Signs and Symptoms of Myasthenia Gravis

- Ptosis (dropping of one or both eyelids)

- Diplopia (double vision)

- Muscle weakness

- Weakness and fatigue possibly can change quickly in intensity over a few days or even a few hours as they are used and resolves when the affected muscles are rested but recur when they are used again.

- The weakness lessens in cooler temperatures.

- Hand grip may alter between normal and weak (milkmaid’s grip).

- Weaken neck muscles

- Proximal limb weakness is common.

- Some people may present with bulbar symptoms (altered voice, dysphagia, nasal choking, regurgitation,).

- Deep tendon reflexes and sensations are normal.

Pathophysiology of Myasthenia Gravis

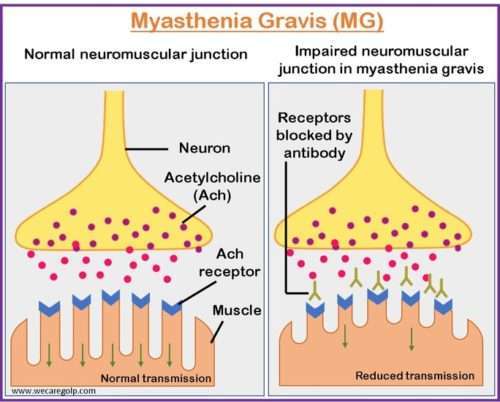

- The brain controls voluntary muscles through nerve impulses that travel down the nerves and reach the neuromuscular junction (NMJ) (the space between the nerve ending and muscle fiber).

- Although the nerve fibers and muscle fibers do not physically connect, they communicate through the release of a chemical called acetylcholine.

- Acetylcholine is a neurotransmitter that transmits signals from nerves to muscles and initiates muscle contraction.

- Once the nerve impulse reaches the nerve ending, acetylcholine is released and travels across the space to attach to multiple receptor sites on the muscle fiber side of the neuromuscular junction.

- The activation of enough receptor sites by acetylcholine triggers muscle contraction.

Myasthenia gravis’s overall pathophysiology includes an autoimmune response that targets acetylcholine receptors (AChRs) at the NMJ, damage caused by complement, involvement of the thymus, and impaired neuromuscular junction function, resulting in muscle weakness and exhaustion.

Autoimmune response

- The body’s immune system mistakenly targets and attacks the AChRs on the surface of muscle cells.

- AChRs are responsible for receiving acetylcholine.

- In MG, autoantibodies that bind to AChRs are produced by the immune system, reducing the number of functional AChRs on the muscle cell membrane and impairing nerve signal transmission to the muscles.

- Although autoantibodies to the AChRs are often the cause of MG, antibodies to Muscle-Specific Kinase (MuSK) protein can also impede transmission at the neuromuscular junction.

Complement-mediated damage

- In addition, the immune system also activates the complement system (a set of proteins) that can trigger inflammation and damage to cells.

- Complement proteins are recruited to the site of autoantibody-AChR binding, leading to inflammation, destruction of AChRs, and further impairment of nerve-muscle communication.

Thymus involvement

- The thymus, a small gland located in the upper anterior part of the chest, plays a role in the development of MG.

- In some cases of MG, abnormalities of the thymus gland can contribute to the production of autoantibodies against AChRs like thymic hyperplasia (an overgrowth of thymic tissue) or thymomas (tumors of the thymus).

Impaired neuromuscular junction (NMJ) function

- The NMJ’s normal function is disrupted in MG by complement-mediated damage and autoantibody-AChR binding.

- As a result, the number and function of AChRs decrease, resulting in weakened muscle contractions, muscle fatigue, and fluctuating muscle weakness that may worsen with activity or stress.

Genetic factors

- Even though the exact causative factor is unknown, some evidence suggests a genetic predisposition to the disease.

- An increased risk of developing MG has been linked to some genetic variations, such as particular HLA genes.

Diagnosis of Myasthenia Gravis

- Neurological examination

- Reflexes

- Muscle tone and strength

- Touch

- Sight

- Balance and coordination

- Fatigability

- Edrophonium test: If muscle strength improves by injecting the chemical called edrophonium chloride the person might have myasthenia gravis.

- Ice pack test: If a person has a drooping eyelid, an ice pack is applied to it for 2 minutes to see whether there is an improvement in myasthenic ptosis or not because neuromuscular transmission improves at a lower temperature.

- Blood test: To check certain antibodies that affect muscle nerve receptors.

- AChR antibody

- Anti-MUSK antibody

- Negative antibody (in case of seronegative myasthenia)

- Repetitive nerve stimulation: The electrodes are used on the muscles of patients to send mild electrical pulses to check whether the nerves show a reaction to the signals or not.

- Single-fiber electromyography (EMG): A thin wire electrode is placed via the skin and inside a muscle that tests the electrical activity between the brain and muscles.

- Imaging: A CT scan or MRI is done to locate a tumor on the thymus gland that could be causing symptoms.

- Pulmonary functioning tests: It is done to see whether the lungs are affected by myasthenia gravis.

Treatment/Management of Myasthenia Gravis

The immune response can be suppressed, neuromuscular transmission can be improved, and symptoms can be managed to improve quality of life. Various single or combinations of treatments can alleviate symptoms of the disease. The management depends on the age, the severity of the disease, and its progression.

Medications

- Cholinesterase inhibitors such as pyridostigmine improve communication between the nerves and muscles, thus improving muscle contraction and strength in some people.

- Corticosteroids such as prednisone suppress the immune system, thus limiting antibody production.

- Immunosuppressants such as azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, cyclosporine, methotrexate, or tacrolimus may be given with corticosteroids but may take several months to show effectiveness.

Intravenous Therapy

These therapies are provided in the short term to treat a sudden worsening of symptoms or before surgery or other therapies.

- Plasmapheresis is similar to dialysis which uses a filtering process to remove the antibodies that block transmission of nerve signals from the nerve endings to skeletal muscle’s receptor sites but effects usually last a few weeks.

- Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) therapy provides normal antibodies to the body, which alters the immune system response in less than a week and lasts up to 3 to 6 weeks.

- Monoclonal antibodies like Rituximab and eculizumab are used for people who do not respond to other treatments because they can have serious side effects.

Surgery

- Some people with myasthenia gravis have a tumor in the thymus gland (thymoma) that requires a thymectomy.

- Removal of the thymus gland might improve myasthenia gravis symptoms even in those persons who do not have the tumor but it can take years to develop.

- The surgery can be done open or as a minimally invasive approach.

- Minimally invasive surgery involves Video-assisted or Robot-assisted thymectomy.

Lifestyle Modification and Home Care

- Small, frequent, soft well-balanced foods improve muscle strength. Unhurried time with frequent breaks is needed for chewing the food.

- Use safety precautions at home by installing grab bars or railings in places like bathrooms and stairs where support is needed. Keep the floors and pathways free of tumbles.

- Use electric appliances like electric toothbrushes, electric can openers, and other power tools like to maintain energy.

- Wear an eye patch to improve double vision while writing, reading, or watching television, and switch the patch periodically to the other eye to help reduce eyestrain.

- Plan the activities like shopping for the time when the energy is high.

Complications of Myasthenia Gravis

Myasthenic crisis

- It is life-threatening respiratory muscle weakness or severe generalized quadriparesis that occurs at least once in their lifetime in about 18% of patients with MG.

- It is often due to an adventitious infection that reactivates the immune system. Respiratory failure may occur rapidly once respiratory insufficiency begins.

Cholinergic crisis

- This is the muscle weakness that can result from taking too many anticholinesterase medications (neostigmine and pyridostigmine).

- A mild cholinergic crisis might be difficult to discriminate from a myasthenia crisis but severe cholinergic crisis results in muscle fasciculation, increased salivation, lacrimation, and heart rate as well as diarrhea that is unlike in myasthenic crisis.

Autoimmune disorders

- People with myasthenia gravis are also at higher risk for some autoimmune disorders like

- Rheumatoid arthritis,

- Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and

- Thyrotoxicosis.

Prevention of Myasthenia Gravis

There are no known ways to prevent myasthenia gravis but we can avoid an exacerbation by:

- Preventing infections with careful hygiene and avoiding sick people

- Treating infections promptly

- Avoiding extremely heated or cold

- Avoiding overexertion

- Dealing with stress effectively

Prognosis

- People with MG can have a normal life expectancy with treatment and therapies.

- Those people who are early diagnosed and receive effective treatment have better outcomes.

- Sometimes people experience remission but for some people quality of life is significantly affected due to the severity of the disease or the severity of side effects from the medication.

Summary

- Myasthenia gravis is an autoimmune, rare, progressive disorder in which autoantibodies disrupt the communication between nerves and skeletal muscle, leading to weakness of the muscles.

- The disorder affects the voluntary muscles of the eyes, mouth, throat, and limbs causing ptosis and difficulty in swallowing and/or breathing.

- The disorder may be seen at any age, but more commonly strikes young women between 20 and 30 years of age and men aged 50 and more.

- Myasthenia gravis is idiopathic, so there is no specific treatment. However, early detection and proper management can help patients live normal lives with greater meaning.

Other Autoimmune Disorders

- Multiple Sclerosis (MS)

- Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS)

- Goodpasture Syndrome (GS)

- Rheumatoid Arthritis

- Vasculitis

- Type 1 Diabetes

- Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE)

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD)

- Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis

References

- Salari, N., Fatahi, B., Bartina, Y. et al. (2021). The global prevalence of myasthenia gravis and the effectiveness of common drugs in its treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Transl Med 19, 516. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-021-03185-7

- Bubuioc, A. M., Kudebayeva, A., Turuspekova, S., Lisnic, V., & Leone, M. A. (2021). The epidemiology of myasthenia gravis. Journal of Medicine and Life, 14(1), 7-16. doi: 10.25122/jml-2020-0145

- Kaminski, J. H. (2023). Myasthenia-gravis. National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD), USA. Retrieved on 2023 Apr 07 from https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/myasthenia-gravis

- Bard, S., Christine, C., Jaime, H. (2022, April 25). Myasthenia-gravis.Healthline. Retrieved on 2023 Apr 06 from https://www.healthline.com/health/myasthenia-gravis