Introduction

Undescended testicle, also called cryptorchidism, is the absence of at least one testicle from the scrotum. It is the most frequent congenital abnormality affecting the male genitalia. Cryptorchidism refers to either an undescended or mal-descended testis which denotes a hidden or obscure testis.

- By the third month of life, 80% of cryptorchid testes have descended. As a result, the actual incidence is close to 1%.

- Although it can affect either side, the right testicle is more frequently affected by cryptorchidism.

- It is obvious that over time, untreated cryptorchidism has harmful consequences on the testes.

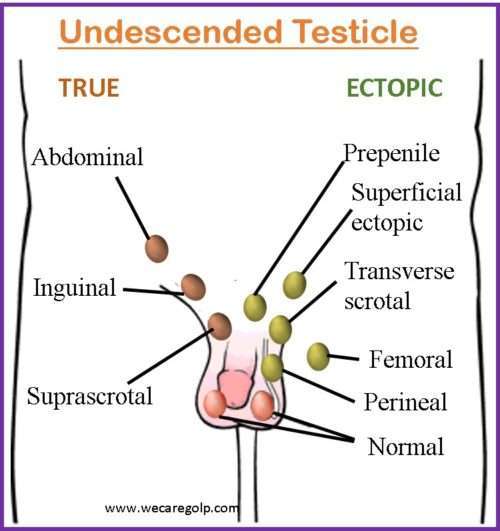

- The testicle can be anywhere outside the scrotum along the “path of descent,” including

- Missing or nonexistent,

- Ectopic from the line of descent,

- High in the retroperitoneal abdomen to the inguinal ring,

- In the inguinal canal,

- Hypoplastic (underdeveloped),

- Dysgenetic (severely abnormal), and

- Unilateral.

- In most cases, the undescended testicle may be palpated in the inguinal canal. In a small percentage of cases, the missing testicle may be in the abdomen or nonexistent.

- Modern diagnosis and therapy of this incredibly prevalent condition depend on an understanding of the anomalies of morphogenesis and the molecular and hormonal milieu associated with cryptorchidism.

Incidence

- Cryptorchidism affects 3% of full-term newborn newborns. This falls to 1% in babies aged six months to one year.

- It affects 30% of preterm male infants.

- UDT affects 7% of the siblings of males with undescended testes.

- The prevalence varies from 4% to 5% at birth to roughly 1% to 1.5% at three months and 1% to 2.5% at nine months.

- UDT affects roughly 1.5% to 4% of fathers and 6% of brothers of cryptorchids.

- The heritability of first-degree male relatives is estimated to be 0.5% to 1%.

- There might be a link between UDT and autism.

- A unilateral undescended testis increases the risk of infertility in 10% to 30% of people. When the condition is bilateral, this rises to 35% to 65% or higher. The likelihood of infertility rising to above 90% depends on whether bilateral cryptorchid testes are treated.

Classification of Undescended Testicle

Based on number

- Unilateral cryptorchidism: One testicle fails to descend into the scrotum. It is more prevalent accounting for 70% of the cases.

- Bilateral cryptorchidism: It is the condition in which both testicles fail to enter the scrotum. With just 30% of instances, it is less prevalent than unilateral cryptorchidism.

Based on location

- High scrotal cryptorchidism: This condition develops when one or more undescended testicles are in the upper scrotum. On physical examination, the testicle(s) may be visible or palpable.

- Low scrotal cryptorchidism: Here, undescended testicle(s) are in the lower portion of the scrotum. It could be challenging to locate the testicles during a physical examination.

- Inguinal cryptorchidism: It is a condition in which the undescended testicle(s) are found in the inguinal canal, which is the tube via which the testicles descend from the belly to the scrotum. In the inguinal region, the testicle(s) may be palpable.

- Abdominal cryptorchidism: When the undescended testicle(s) are found in the abdomen. Physical examination may reveal that the testicle(s) are not palpable.

Causes and Risk Factors of Undescended Testicle

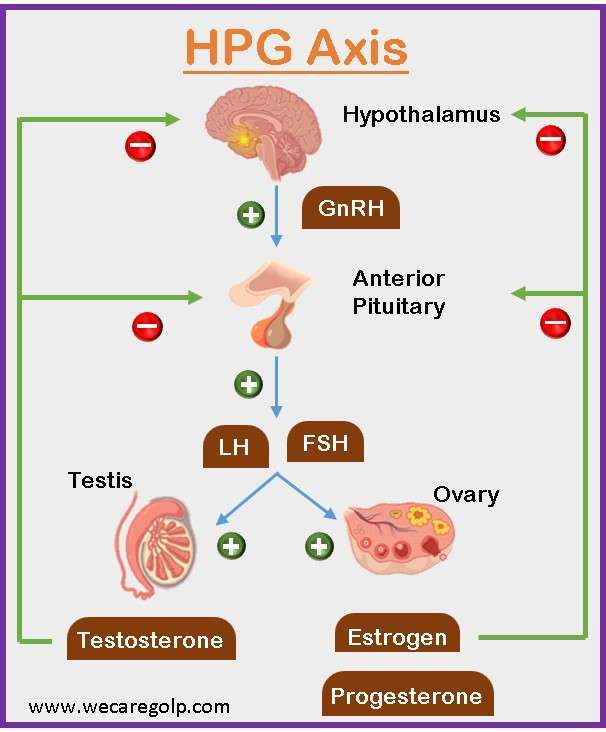

- Hormonal factors: The testes generally descend into the scrotum around the 28th week of pregnancy after developing in the abdomen throughout fetal development. Due to some impairment in the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis (HPG axis), the hormones generated by the testes and the fetal pituitary gland, specifically testosterone and anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH), regulate this process. Undescended testes may result from a hormone deficit.

- Genetic factors: Research has indicated that undescended testes have a genetic component. Fathers with undescended testes are more likely to have children with a similar condition.

- Testes that have not descended into the scrotum are more likely to be present in premature children because they may not have had enough time to do so before delivery.

- Blood vascular abnormalities (hemangioma, vasculitis) in the testicles can hinder the testes from descending.

- Insufficient fetal development can cause the testicles to remain undescended (intrauterine growth retardation).

- Anatomical obstruction in the pathway of descent.

- Intra-abdominal pressure appears to be involved in testicular descent as well. Among the many disorders linked with decreased pressure are prune belly syndrome, cloacal exstrophy, omphalocele, and gastroschisis. Each is linked to a higher chance of undescended testes.

- Environmental factors: The incidence of undescended testes may be increased by exposure to certain chemicals or toxins during pregnancy, such as pesticides or dioxins. Smokers are more likely to give birth to male children without descending testis.

- Anatomical abnormalities: anomalies of the testis, epididymis, and vas deferens, improper attachment of the gubernaculum, patent processus vaginalis and inguinal hernia, and anomalies of the inguinal canal.

Other possible risk factors

- Smaller placental weight

- Gestational diabetes

- Chemicals endocrine disruptors which can interfere with normal fetal hormone balance

- Maternal obesity

- Pesticides

- Alcohol consumption during pregnancy

- Invitro fertilization

- Family history

- Ibuprofen

- Preeclampsia

- Congenital malformation syndromes – Down syndrome, Prader–Willi syndrome, and Noonan syndrome

- Persistent Mullerian duct syndrome

Signs and Symptoms of Undescended Testicle

- Asymptomatic

- Absence of one or both testicles in the scrotum (also known as empty scrotum when both testicles are not present)

- Small and flat scrotum if both testicles are undescended

- Lopsided scrotum if one testicle is undescended

- Lack of a palpable scrotal testicle

- Inguinal hernia

- Swelling in the groin

- Decreased degree of scrotal rugae or ridges

- Disturbed self-image

Pathophysiology of Undescended Testicle

- The testes normally originate in the abdomen during fetal development and begin to descend towards the scrotum about the 28th week of gestation.

- Hormonal signals, notably testosterone and AMH, released by the testes and the embryonic pituitary gland, control the descent of the testes.

- AMH induces regression of the Mullerian ducts, which are female reproductive organs that would otherwise impede testicular descent, whereas testosterone stimulates the formation of the gubernaculum, a fibrous cord that connects the testes to the scrotum.

- The testes descend through the inguinal canal, which is a tiny passageway between the abdominal wall and the scrotum.

- If the testes fail to descend properly, they can become trapped in the abdomen or the inguinal canal, resulting in undescended testes or inguinal hernia.

Diagnosis of Undescended Testicle

History taking and physical examination

- Palpation is a fundamental method for evaluating UDT. It enables distinction between retractile and gliding testes, as well as between palpable and nonpalpable testes. A patient should be checked both lying down (for younger boys) and standing (for older boys) in a warm environment with warm hands.

- The size, turgor, existence of hernia or hydrocele, any palpable para-testicular abnormalities, and other factors should all be thoroughly inspected in gonads.

Tests

According to American Urological Association (AUA), more than 70% of cryptorchid testes are palpable by physical examination and do not require imaging in the hands of an expert physician. The difficulty is determining if the testis is present or absent and where the viable nonpalpable testis is in the remaining 30% of instances.

For unilateral or bilateral undescended testes with hypospadias or bilateral nonpalpable testis:

- Hormone level tests such as gonadotropins and Mullerian inhibitory substances to rule out the complicated intersex condition

- Progesterone 17-hydroxylase

- Luteinizing hormone (LH)

- Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH)

- Testosterone

- Depending on preliminary findings, additional laboratory tests

For anorchia (absence of both testes):

- LH test

- FSH test

- Testosterone levels (both before and after hCG activation of the testis)

Imaging

Before the referral for surgery, AUA guidelines advise avoiding imaging investigations in males with cryptorchidism. The usefulness of radiologic investigations to pinpoint the testicles is quite low. Radiologic testing for undescended testes is only 44% accurate overall.

- When evaluating a nonpalpable testis, computed tomography (CT) scanning and ultrasonography provide significant false-negative rates and are not advised.

- Although ultrasonography is excellent for determining the size of the inguinal testis but less reliable for abdominal testis; computed tomography (CT) – may be useful for bilateral impalpable testes; conducted under general anesthesia in young infants;

- The sensitivity of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with or without angiography has been reported to be close to 100%, however, it is costly, needs anesthesia, and may not be cost-effective.

Ultrasonography, CT scanning, and MRI have not yet been found to be more useful than a pediatric urologist’s examination.

Treatment of Undescended Testicle

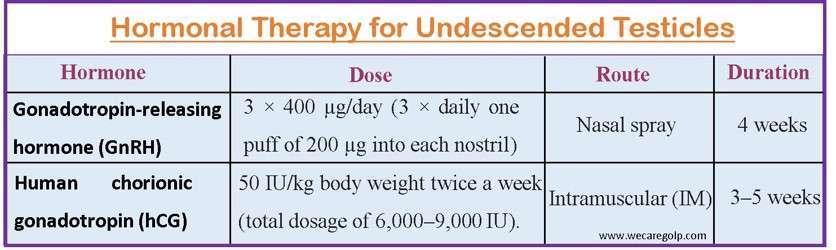

Hormonal therapy

- Since general anesthesia is not ideal for newborns with low muscle tone and a high risk of underlying respiratory impairment, hormonal therapy is recommended for the treatment of undescended testes before surgery.

- Human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) is the hormone that is utilized the most frequently. Following a series of HCG injections, the condition of the undescended testicle is reviewed. The stated success rate ranges from 5% to 50%.

- Hormonal treatment is often administered with hCG, gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH), or a combination of the two. It can be used as a neoadjuvant therapy before orchiopexy or as a supplement following early surgery for UDT.

- Hormone therapy will also confirm Leydig cell responsiveness and cause further development of a small penis due to an increase in testosterone levels.

But, the AUA Guidelines suggest that because of the poor response rates and lack of evidence for long-term success, providers should not employ hormone treatment to promote testicular descent.

Surgical Management

- AUA Guidelines state that between the ages of 6 and 18 months, surgery is advised for congenitally undescended testes.

- To maximize testicular development and fertility, several specialists advise undergoing surgery as soon as possible, at approximately six months.

- Corrected age is used to identify the best time to do surgery on preterm infants.

- Early orchidopexy is the typical, accepted treatment since the longer the cryptorchid testis is left untreated, the greater the loss of germ cells and the decline in fertility.

Orchidopexy

A surgical treatment for correcting an undescended testicle is known as an orchidopexy. In most cases, laboratory tests are unnecessary in patients with unilateral cryptorchidism. In the absence of severe accompanying morbidities, orchiopexy is commonly performed as same-day surgical surgery. Between the ages of 6 and 12 months, definitive surgical treatment should be conducted.

Inguinal or scrotal orchiopexy

It is advised for palpable undescended testes.

- An incision is done in the high scrotum, median scrotal raphe, scrotal high edge, or groin. Depending on the size of the incision, a variety of retractors can be employed.

- Inguinal incisions as tiny as 1 cm can be made. Scrotal incisions can be bigger since they heal hidden, especially in the median raphe.

- The testis or the cord might be addressed first; in scrotal situations, the testis is located first. The testis can be addressed first in an inguinal approach, or the external oblique fascia can be opened proximal to the external ring and the cord approached first.

- Because everything does not go into the external ring when approaching the testis initially, all the cremasteric muscles are separated as well.

- Separating the hernia sac from the vas and testicular arteries is the most challenging portion of the case. This may be approached from either the front or the back. The posterior technique is far more straightforward to teach and understand.

- The location and security of the testis in the scrotum varies. Most people would agree that a sub-dartos pouch is ideal. Some surgeons do not stitch the testis, whilst others utilize absorbable or non-absorbable sutures. Some will just shut the groin passage.

Laparoscopic orchiopexy

Exploratory laparoscopy is advised for nonpalpable undescended testis under anesthesia.

- Laparoscopic orchiopexy with vascular preservation: In this method, the testis is removed from a triangular pedicle that contains the gonadal vessels and the vas.

- Laparoscopic one-stage Fowler Stevens (FS) orchiopexy: The gonadal arteries are separated, and the testis is dissected and pulled down in one stage from a pedicle of the vas.

- Laparoscopic two-stage Fowler Stevens orchiopexy:

- The arteries are separated using clips, but the testis is not dissected for six months to allow for optimum collateral growth.

- The intraabdominal testis is fastened to a position one inch (2 cm) medial and superior to the contralateral anterior superior iliac spine, which produces traction, in a two-stage laparoscopic traction-orchidopexy (Shehata procedure).

- The testis is kept in place for three months before undergoing ipsilateral subdartos orchidopexy by laparoscopic. This method can be used instead of the two-stage Fowler Stevens orchidopexy.

- Its key benefit is that it allows for the relocation of an intraabdominal testis into the scrotum without sacrificing the principal testicular arteries. When a single-stage laparoscopic orchidopexy cannot be performed owing to insufficient length, this option should be explored.

- It has a very high success rate in terms of preserving testicular vasculature without atrophy. The overall success rate for this approach ranges from 84% to 100%.

Complications of Undescended Testicle

- Lower fertility (bilateral instances),

- Testicular germ cell malignancies (overall risk less than 1%),

- Testicular torsion,

- Inguinal hernias, and

- Psychological issues.

Complication from treatment

Human Chorionic Gonadotropin (hCG) therapy

- Temporary adverse effects of hCG therapy

- Penis enlargement

- Pubic hair development

- Groin and injection site pain

- Erection pain

- Behavioral issues such as hyperactivity and hostility

- Inflammation-like morphological alterations

- Germ cell death (which is linked to reduced testis volume and greater FSH levels in adulthood)

- Children aged 1-3 years are mostly affected

Intraoperative

- Ilioinguinal nerve injury

- Damage to the vas deferens

Postoperative early

- Hematoma formation

- Wound infection

Postoperative late

- Testicular atrophy

- Testicular retraction

- Postoperative torsion

Prevention of Undescended Testicle

- Usually, prevention is impossible.

- The best way to prevent undescended testicles is to prevent preterm birth. The factors that could trigger early labor (e.g., medications, smoking, infections, etc.) should be avoided and good antennal care is helpful to prevent preterm birth.

Prognosis

- The prognosis for an undescended testis is affected by several factors, including the age at which the problem is discovered, the location of the testis, and whether the issue is unilateral (affecting just one testis) or bilateral (affecting both testes).

- The prognosis is generally favorable if an undescended testis is found and treated early, often by the age of one year. The most common treatment is orchidopexy, which entails bringing the testis down into the scrotum. Orchidopexy has a high success rate, with most patients regaining normal testicular function and fertility.

- However, if the problem is not corrected or the testis is not moved down into the scrotum until later in infancy or adolescence, difficulties may occur. Reduced fertility, an increased risk of testicular cancer, and testicular torsion, a painful twisting of the testicle that can lead to tissue death and necessitate emergency surgery, are all possibilities.

- Early diagnosis and treatment of undescended testis are critical for improving long-term prognosis. Patients with this disease should see their healthcare practitioner frequently to monitor for any potential problems.

Summary

- The absence of at least one testicle from the scrotum is known as undescended testis (UDT) or cryptorchidism.

- Male newborns with undescended testes are a very common occurrence, particularly in those who were delivered early.

- It is crucial to ascertain if a non-intrascrotal testis is palpable or not, as well as whether the discovery is unilateral or bilateral after it has been identified.

- As no existing modality has been demonstrated to be sufficiently sensitive or specific to help in management decisions, imaging should not be performed in this workup.

- Patients with UDTs who were discovered after the age of six months should be sent to a professional for treatment so that surgery might be done within a year.

- Orchidopexy has a high success rate, especially if the problem is identified and treated quickly. To monitor for any possible problems and improve long-term results, regular follow-up treatment is crucial.

References

- Docimo, S. G., Silver, R. I., & Cromie, W. (2000). The undescended testicle: diagnosis and management. American Family Physician, 62(9), 2037-2044. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2000/1101/p2037.html

- Goel, P., Rawat, J. D., Wakhlu, A., & Kureel, S. N. (2015). Undescended testicle: An update on fertility in cryptorchid men. The Indian journal of medical research, 141(2), 163. doi: 10.4103/0971-5916.155544

- Lee, P. A., & Houk, C. P. (2013). Cryptorchidism. Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes and Obesity, 20(3), 210-216. Doi: 10.1097/MED.0b013e32835ffc7d

- Gurney, J. K., McGlynn, K. A., Stanley, J., Merriman, T., Signal, V., Shaw, C., … & Sarfati, D. (2017). Risk factors for cryptorchidism. Nature Reviews Urology, 14(9), 534-548. https://www.nature.com/articles/nrurol.2017.90

- Kollin, C., & Ritzen, E. M. (2014). Cryptorchidism: a clinical perspective. Pediatric endocrinology reviews: PER, 11, 240-250. https://europepmc.org/article/med/24683948

- Leslie, S. W., Sajjad, H., & Villanueva, C. A. (2022). Cryptorchidism. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470270/

- Hutson, J. M., & Clarke, M. C. (2007, February). Current management of the undescended testicle. Seminars in Pediatric Surgery, 16(1), pp. 64-70. WB Saunders. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2006.10.009

- Sumfest, J.M. (October, 2022). Cryptorchidism. Medscape. Retrieved on 2023, April 21 from https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/438378-overview