Introduction

Hypospadias is a developmental disorder of the anterior urethral and penile organs. During weeks 8–14 of pregnancy, the urethra develops improperly in boys with hypospadias. The abnormal opening may appear anywhere between the area just below the penis’s tip and the scrotum. It can range in severity from mild to severe, depending on the case.

- The urethral entrance is ectopically positioned on the ventral side of the penis, close to the tip of the glans penis, which may be splayed wide in this situation.

- It is distinguished by abnormal development of the ventral foreskin of the penis and the urethral fold, which results in the incorrect location of the urethral opening.

- The external urethral meatus may be mispositioned to varying degrees and may also have concomitant penile curvature in hypospadias.

- The presence of additional genitourinary malformations in individuals varies depending on the location of the lesion.

- In more severe instances, the urethral opening may be as close as the scrotum or perineum. With more proximal urethral abnormalities, the penis may exhibit concomitant ventral shortening and curvature, known as chordee.

Incidence

- Hypospadias is the most prevalent penile congenital abnormality and the second most frequent congenital condition in boys after cryptorchidism (undescended testicle).

- It is generally thought to affect between 0.3% and 0.8% of live male newborns.

- In the United States, one out of every 250 males (0.4%) has hypospadias, whereas the estimated rate in Denmark is 0.5% to 0.8%.

- According to South American research, the worldwide frequency is 11.3 per 10,000 infants (less than 0.1%).

- In contrast, in other Asian nations, such as Japan, the incidence is estimated to be about 0.6-0.7 instances per 1000 live births.

- The incidence, however, could be higher in some communities or in children who were born prematurely.

- According to some research, the prevalence may be rising over time, albeit this might be because diagnostic standards have changed and the disorder is now more well understood.

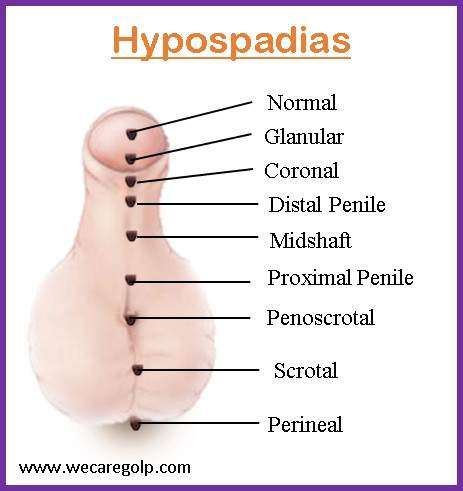

Classification of Hypospadias

Distal hypospadias

Distal hypospadias is the most prevalent kind of hypospadias (60% to 70%). It is also known as anterior or minor hypospadias, and it encompasses glanular and sub-coronal hypospadias. The urethral opening lies near the tip of the penis rather than in the middle of the glans, making glanular hypospadias the mildest kind of condition. The urethral opening is situated at the base of the glans in individuals with coronal hypospadias.

Midshaft hypospadias

Midshaft hypospadias, commonly known as penile hypospadias, encompasses distal, midshaft, and proximal hypospadias.

Posterior hypospadias

Penoscrotal, scrotal, and perineal hypospadias are all examples of posterior hypospadias. In the penoscrotal, the urethral opening is located at the base of the scrotum. Perineal hypospadias is the most severe form where the urethral opening is positioned in the perineum, which is the region between the scrotum and the anus.

Causes of Hypospadias

The exact cause of hypospadias is unknown. However, the following risk factors can be the cause in most cases.

Genetic factors

Hypospadias is four times more common in monozygotic twins than in singletons, which may indicate a hereditary predisposition. This result could be explained by the fact that a single placenta only produces enough human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) for one baby at a time, leaving the other two in need at crucial urethral development stages. It has been observed more frequently in boys with a family history of hypospadias, and inheritance is thought to be polygenic.

Hormonal factors

Males with reduced androgen levels or with receptors that are less sensitive to androgens frequently exhibit hypospadias. Hypospadias has been linked to mutations in the 5-alpha reductase enzyme, which transforms testosterone (T) into stronger dihydrotestosterone (DHT). Males born through assisted reproduction appear to have a threefold greater incidence of hypospadias. This could be an indication of maternal exposure to progesterone, which is frequently given during In vitro fertilization (IVF) procedures. Progesterone functions as a competitive inhibitor of the T-to-DHT conversion and is a substrate for 5-alpha reductase.

Environmental factors

An increased incidence of hypospadias has also been related to endocrine disruption brought on by environmental factors. Environmental toxins with strong estrogenic activity are prevalent in industrialized society and are consumed as pesticides on fruits and vegetables, endogenous plant estrogens, in milk from breastfeeding pregnant dairy cows, and in medications like phthalates. The risk of hypospadias has been linked to anti-seizure drugs. The correlation between hypospadias and low birth weight, maternal age, and increasing parity has been seen as very high in different studies.

Signs and Symptoms of Hypospadias

- Abnormal positioning of the urethral opening

- Curved or bent penis

- Enlarged foreskin

- Difficulty with urination

- Abnormal scrotum positioning

- Undescended testes

- Abnormal development of testes/smaller testes

- Wear urine stream

- Incomplete emptying of the bladder

Pathophysiology of Hypospadias

The abnormal or incomplete urethral closure during the initial weeks of embryonic development is the primary pathophysiological event that leads to the development of hypospadias. The development of the external genitalia happens in two stages.

The first stage, which lasts between the fifth and eighth weeks of pregnancy, is defined by the absence of hormonal stimulation during the creation of the primordial genitalia. During this stage, mesodermal cells that are positioned laterally to the cloacal membrane produce the cloacal folds. These folds break posteriorly into urogenital folds that encircle the urogenital sinus and anal folds, and they unite anteriorly to create the structure known as the genital tubercle (GT). The lateral plate mesoderm, surface face ectoderm, and endodermal urethral epithelium are the three cell layers that make up the GT. The latter serves as the primary signaling hub for the growth, differentiation, and development of the GT.

The development of the gonads into testes in males with chromosomes XY marks the beginning of the second phase, which is a hormone-dependent stage. The urethral groove and GT elongation are two extremely significant effects of testosterone produced in the testes. The distal section of the urethral groove, known as the urethral plate, is defined laterally by the urethral folds and extends into the glans penis. The skin of the penis is created from the outermost layer of ectodermal cells, which fuses into the ventral part of the phallus and produces the median raphe. The urethra finally develops when the urethral folds fuse.

The development of various malformations, such as hypospadias, chordee (abnormal curvature of the penis), or aberrant penile foreskin formation, may result from any genetic disruption or modification in the signaling pathways regulating male external genital development and urethral growth.

Diagnosis of Hypospadias

- The first indications of hypospadias are usually discovered during a physical examination performed soon after birth. Boys with hypospadias are commonly identified by their improperly positioned meatus and variable degrees of ventral penile curvature.

- It has not been shown that any laboratory tests are useful in the diagnosis and treatment of hypospadias. Hormonal testing may be required when a disorder/difference of sex development (DSD) is detected.

- Upper-urinary tract abnormalities are uncommon in hypospadias individuals and do not warrant regular imaging unless additional organ system anomalies are present. Other associated findings (e.g., enlarged prostatic utricle, low-grade vesicoureteral reflux [VUR]) are more common but have little clinical significance unless other symptoms warrant evaluation.

Treatment of Hypospadias

Surgical Therapy

Within the first few weeks of life, patients should be referred for a surgical evaluation.

The following are the aims of surgical treatment:

- To correct any curvature and establish a straight penis (orthoplasty)

- Creating an artificial urethra with a meatus-like opening at the apex of the penis (urethroplasty)

- To undergo glansplasty, which involves reshaping the glans into a more naturally conical shape

- To make up the penile skin in a suitable manner aesthetically

- To create a scrotum that seems normal

The penis after surgery should be acceptable cosmetically, allow the patient to urinate while standing, and be suitable for future sexual activity.

Surgical correction for hypospadias can be performed at any age; however, the majority of researchers favor operational intervention between the ages of 6 and 18 months.

Snodgrass technique

The Snodgrass Technique, sometimes referred to as the tubularized incised plate (TIP) repair, is the method most frequently employed to treat hypospadias. To develop a new urethra, a tube must be formed from the base of the penis to its tip. An incision is made on the underside of the penis, and the skin is then folded to form the tube. After that, the incision’s edges are sewn together to create the tube. After that, the urethral opening is relocated to the tip of the penis.

Tubularized incised plate (TIP) urethroplasty

The TIP Technique is used to treat moderate to severe hypospadias. It is similar to the Snodgrass procedure, except instead of folding the skin to make a tube, a flap of skin is made and then stitched to form a tube. After that, the urethral entrance is relocated to the tip of the penis.

Onlay island flap urethroplasty

This technique is performed for more severe hypospadias instances where the urethra is considerably displaced. It entails utilizing tissue from the inner lining of the mouth or cheek to build a new urethra. The tissue is sutured to the bottom of the penis in the shape of an island flap. After that, the urethral entrance is relocated to the tip of the penis.

Two-stage repair

This procedure is used for severe cases in which the urethra is short or nonexistent. A graft is taken from the mouth (inner cheek or lower lip or tongue) and utilized to build a new urethra in the first step. Suture the graft to the underside of the penis. The graft is then utilized to finish the urethra in the second step, and the urethral opening is moved to the tip of the penis.

Hormonal Therapy

Although there is no known medical treatment, hormonal therapy has been used as an adjunct to surgical therapy in infants with extremely small phallic sizes. Preoperative testosterone or HCG injection has been utilized to enhance penile development; some have observed chordee improvement with decreasing the degree of hypospadias. It is a concern that prepubertal androgen therapy may limit normal genital growth during puberty, but this has not been proven clinically. Because of the varied transcutaneous absorption of hormone creams, they are normally avoided.

Complications of Hypospadias

- Erectile problem, especially if associated with chordee

- Painful or weak/dribbling ejaculation

- Difficulty urinating while standing

Complications from surgery

- Urethral stenosis

- Glans dehiscence

- Urethrocutaneous fistula

- Meatal stenosis

- Urethral diverticulum or urethrocele

- Cosmetic issues: Excess residual skin, skin tags, inclusion cysts, skin bridges, suture tracts

- Hair-bearing urethra

- Erectile dysfunction

- Recurrent or persistent penile curvature

- Spraying or misdirected urinary stream and/or irritative symptoms

- Balanitis xerotica obliterans of the urethra leading to strictures

Prevention of Hypospadias

- Avoid chemicals during pregnancy: Phthalates, for example, may increase the risk of hypospadias. Many of these substances are present in plastics and personal care items. The risk might be reduced by avoiding these substances as much as feasible.

- Avoid smoking and drinking while pregnant since these behaviors may increase the risk of developing hypospadias.

- Genetic counseling may help assess the risk of having a child with hypospadias if there is a family history of the condition. Genetic testing can help to find any inherited factors that can make it more common.

- A healthy pregnancy requires adequate prenatal care. Regular prenatal checkups will help find any potential hypospadias risk factors and make sure the baby is growing normally.

Prognosis

- Over the last three decades, the prognosis has significantly improved. Earlier therapies were beset with weak technical abilities, a limited understanding of anatomy, and ineffective surgical scheduling.

- Many individuals continue to struggle with cosmesis-related psychological issues, while others continue to have unhappy sex lives.

- Newer hypospadias repair treatments are constantly evolving; the availability of tissue glues and laser devices has resulted in better and faster wound healing.

- However, it should not be forgotten that this condition has a significant psychological impact on the individual, and long-term follow-up is required.

Summary

- Hypospadias is a congenital disorder in which the urethral opening is positioned on the bottom of the penis rather than the tip.

- It is the most prevalent penile congenital abnormality and the second most frequent congenital condition in boys after cryptorchidism.

- Although the precise cause of hypospadias is unknown, it is thought to be a combination of genetic and environmental factors.

- It can range in severity from moderate to severe, and treatment typically entails surgery to relocate the urethral opening to the tip of the penis.

- The surgery employed is determined by the location and degree of the hypospadias. Although recovery time after surgery varies, most children can resume normal activities within a few weeks.

References

- Baskin, L. S., & Ebbers, M. B. (2006). Hypospadias: anatomy, etiology, and technique. Journal of pediatric surgery, 41(3), 463-472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.11.059

- Brouwers, M. M., Feitz, W. F., Roelofs, L. A., Kiemeney, L. A., De Gier, R. P., & Roeleveld, N. (2007). Risk factors for hypospadias. European journal of pediatrics, 166, 671-678. DOI 10.1007/s00431-006-0304-z

- Donaire, A. E., & Mendez, M. D. (2018). Hypospadias. StarPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482122/

- Gatti, J.M. (2021, Au 23). Hypospadias. Medscape. Retrieved on 2023, April 16 from https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1015227-overview#a1

- Kraft, K. H., Shukla, A. R., & Canning, D. A. (2010). Hypospadias. Urologic Clinics, 37(2), 167-181. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ucl.2010.03.003

- Springer, A., Van Den Heijkant, M., & Baumann, S. (2016). Worldwide prevalence of hypospadias. Journal of pediatric urology, 12(3), 152-e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpurol.2015.12.002

- Stein, R. (2012). Hypospadias. European Urology Supplements, 11(2), 33-45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eursup.2012.01.002

- Van der Horst, H. J. R., & De Wall, L. L. (2017). Hypospadias, all there is to know. European journal of pediatrics, 176, 435-441. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00431-017-2864-5