Introduction

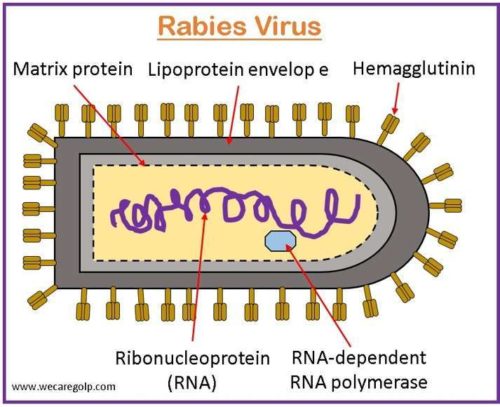

Rabies is a preventable viral zoonotic illness caused by the bite of rabid animals. The rabies virus is a single-stranded, negative-sense RNA virus belonging to the family Rhabdoviridae and the genus Lyssavirus.

- The virus impacts the body in two ways.

- It may move to the brain directly from the peripheral nervous system.

- Because the immune system of the host cannot detect it there, it can multiply in muscle tissue. The neuromuscular connections serve as their entry point into the neurological system.

- All mammals with warm blood are prone to contracting the rabies virus (RABV).

- It is almost always fatal, although infection can be avoided by promptly administering post-exposure prophylaxis and caring for open wounds properly.

- In rabies-endemic areas, RABV transmission by dogs is to blame for up to 99% of human rabies cases.

- Yet, only a small number of human cases of rabies have been linked to wildlife (such as foxes, wolves, jackals, mongoose, raccoons, skunks, and bats).

- The virus is found in the saliva of infected animals, and through the saliva, it can spread to humans and other animals.

- The greatest documented case-fatality rate for an illness is rabies, which is close to 100%. Rural communities are disproportionately impacted, bearing the heaviest burden, and having the least access to accessible preventive care.

- This fatal condition affects the CNS and causes severe neurologic symptoms that ultimately lead to an infection in the brain and death.

- Because there is no effective medication for symptomatic disease, immunization, and human rabies immunoglobulin are the cornerstones of care.

Incidence

- An estimated 59,000 human deaths are related to rabies each year.

- Dog rabies is still prevalent in many nations, and exposure to rabid dogs still accounts for approximately 90% of human exposures to rabies and 99% of all human rabies fatalities globally.

- With an average of 50 reported cases per year, the first half of the 20th century saw the highest number of yearly human deaths.

- Data on dog bites, which are detected more commonly in males than in females, indicate that males may have increased exposure to rabid animal vectors due to possible greater contact in particular geographic areas.

- There were 125 recorded human rabies cases in the United States from 1960 to 2018, with almost a quarter coming from dog bites while traveling abroad.

- Bats were responsible for 70% of the infections that people in the United States contracted.

Incubation Period

- Most cases take 1-3 months to incubate.

- This can last anywhere from more than a year to less than a week (in the event of direct nerve inoculation).

- The incubation period may change depending on the following factors:

- The exposure site’s proximity to the brain

- The kind of rabies virus

- Any immunity that may already exist

Types of Rabies

Furious or encephalitic rabies

- It affects 80% of human cases.

- Those who have it are more likely to exhibit

- Hyperactivity,

- Excitable behavior,

- Hallucinations,

- A lack of coordination,

- Hydrophobia (fear of water), and

- Aerophobia (fear of draughts or fresh air).

- Cardio-respiratory arrest results in death after a few days.

Paralytic rabies

- Around 20% of all human cases of rabies are paralytic, also known as “Dumb” rabies.

- Compared to the furious type of rabies, this variant has a more gradual progression.

- Starting at the site of the injury, muscles gradually paralyze.

- Death eventually happens once a slow-motion coma sets in.

- The underreporting of the disease is a result of the frequent misdiagnosis of the paralytic type of rabies.

Causes of Rabies

- A neurotropic virus of the family Rhabdoviridae, genus Lyssavirus, and subgroup rabies virus is the causative factor behind rabies.

- The most frequent way to contract it is by biting a rabid animal or an animal that has the rabies virus.

- The virus can enter the body through an opening in the skin, such as a bite wound, and is carried in the saliva of the rabid animal.

Risk Factors of Rabies

Factors that can increase the risk of contracting the disease include:

- Traveling to or living in developing nations where rabies is more prevalent.

- Engaging in activities that could expose you to wild animals that may carry the virus.

- Exploring caves where bats live or camping without taking precautions to keep animals away from the campsite.

- Working as a veterinarian.

- Working in a laboratory with the rabies virus.

- Head or neck wounds, which may make it easier for the rabies virus to get to your brain faster.

- Bites from infected animals.

- Exposure to the urine or other secretions of sick animals.

- Transplantation of organs from contaminated donors.

Mode of Transmission of Rabies

- It is transmitted through direct contact between the virus (e.g., in contaminated saliva), and mucous membranes or wounds.

- The inhalation of virus-containing aerosol (such as in bat-inhabited caves) is a rare way to contract rabies.

- Human-human transmission has never been confirmed, except for organ transplants from rabid patients.

Signs and Symptoms of Rabies

There are four main stages in the progression of rabies.

- Incubation

- Prodrome

- The acute neurologic period

- Coma and death

Incubation

- Depending on where the virus entered the body and the number of viral particles involved, it typically lasts between two and three months and can last anywhere from one week to one year.

- The effects are likely to manifest faster the closer the bite is to the brain.

- Rabies is typically lethal by the time symptoms show up.

- Without waiting for symptoms to appear, anyone who has been exposed to the virus should get medical attention right away.

Prodrome

- Early flu-like symptoms

- Fever of at least 100.4°F (38°C)

- Headache

- Worry

- Feeling generally ill

- A sore throat and a cough

- Nausea and vomiting

- Pain at the bite site

Acute neurological phase

- Neurologic symptoms such as disorientation and aggression start to appear at this point.

- Convulsions

- Partial paralysis

- Involuntary muscle twitching

- Stiff neck muscles

- Hyperventilation and breathing difficulties

- Excessive salivation

- Foaming at the mouth

- Hydrophobia (fear of water)

- Hallucinations

- Nightmares, and insomnia

- Priapism (permanent erection in men)

- Photophobia (fear of light)

- Breathing speeds up and fluctuates at the end of this stage.

Coma and Death

- A person may go into a coma, and most of them pass away within three days.

- Almost no one survives rabies during the coma stage, not even with supportive care.

Pathophysiology of Rabies

- After viral transmission, the rhabdovirus targets the central nerves as it moves through the peripheral nervous system, causing encephalomyelitis (the combination of encephalitis and myelitis).

- The virus moves from peripheral nerves to the central nervous system (CNS), infecting highly innervated regions before returning to the peripheral nervous system (e.g., salivary glands).

- The “frothing” is caused by hypersalivation, and with the mere sight, taste, or sound of water, sufferers may have a severe pharyngeal muscular spasm.

- Animals typically pass away within ten days, although the incubation period that follows vaccination can run anywhere from two weeks to six years, with an average of a few months.

- The virus ultimately has an impact on the central nervous system, frequently having a more significant impact on the brainstem.

- In the end, it is thought that the virus affects neurotransmission, and both virus- and cell-dependent mechanisms may be involved in apoptosis.

- The infection eventually leads to total nervous system breakdown, which results in an immediate demise.

- When clinical signs appear, it is always lethal.

Diagnosis of Rabies

- History: Determine the type of animal interaction, the animal’s rabies vaccination status, and if the animal is available for testing.

- Physical Examination: Patients with furious rabies exhibit episodic delirium, psychosis, restlessness, thrashing, muscular fasciculations, convulsions, and aphasia. Autonomic instability is often seen in furious rabies patients.

- Direct fluorescent antibodies test (DFA): The DFA test is based on the finding that rabies virus proteins (antigen) are present in the tissues of animals with rabies virus infection; since rabies is prevalent in neural tissue (rather than blood, like many other viruses), the best tissue to test for rabies antigen is the brain.

- Histologic analysis: In some situations, histologic analysis of a biopsy or autopsy tissues can help identify cases of rabies that have not been routinely tested for the disease.

- Immunohistochemistry: More sensitive than histologic staining techniques like H&E and Sellers stains, IHC approaches for rabies detection offer specific and sensitive ways to identify rabies in formalin-fixed tissues. Like the DFA test, these processes use particular antibodies to identify rabies virus inclusions.

- Electron Microscopy: Rhabdoviruses look like bullet-shaped particles under an electron microscope. Viral ultrastructure can be studied using electron microscopy, which allows for detailed observation of both the structural elements of viruses and their inclusions.

- Amplification methods: The rabies virus can be amplified without the use of animals in mouse neuroblastoma (MNA) and baby hamster kidney (BHK) cells. Biochemical techniques can also be used to amplify the rabies virus’ nucleic acid.

Treatment/Management of Rabies

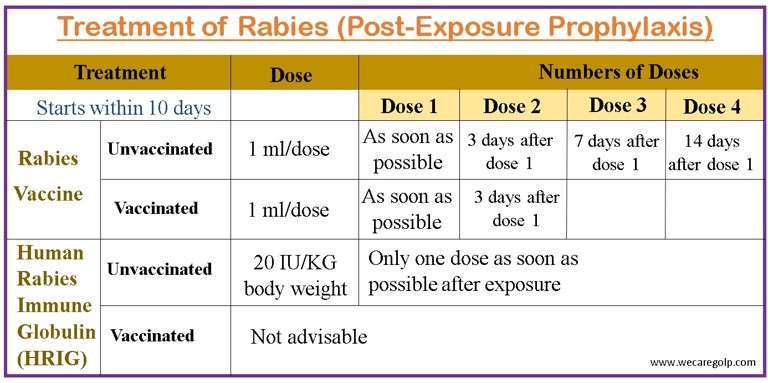

Post-Exposure Prophylaxis

- Post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) is the best option to prevent developing rabies that includes

- Human rabies immune globulin (HRIG) and

- The rabies vaccination

- It should be given as soon as possible (within 10 days) after exposure.

- The combination of HRIG and vaccination is advised for a bite and non-bite exposures in cases where the patient has never received a prior rabies vaccination.

Human Rabies Immune Globulin (HRIG)

- For previously unvaccinated individuals, HRIG is only given once at the start of anti-rabies prophylaxis.

- Until the body can react to the vaccine by actively manufacturing its own antibodies, this will serve as an immediate source of antibodies.

- If at all feasible, the entire HRIG dosage should be completely injected into and around the incisions.

- Any extra dose should be intramuscularly injected at a different location from where the vaccine was administered.

- The HRIG dosage is 20 IU per kg of body weight. Everyone of any age can use this recipe, including young children.

- HRIG is not advisable if the patient is immune previously.

- HRIG should not be given in the same syringe as the vaccine either.

- No more than the indicated amount should be administered because HRIG may partially decrease active antibody production.

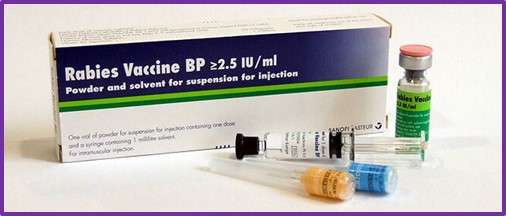

Rabies Vaccination

- To previously unvaccinated individuals, a regimen of four 1-mL doses of the HDCV or PCEC vaccination should be intramuscularly delivered.

- The four-dose course’s initial dose needs to be given as soon as feasible following exposure.

- On days 3, 7, and 14 following the initial immunization, further doses should be given. Adults should always receive the immunization intramuscularly in the deltoid region (arm).

- Two doses of vaccine on days 0 and 3 will be administered if the patient is already immune.

- The anterolateral side of the thigh is also appropriate for children.

Wound Care

- After exposure, all bites and scratches should be treated as quickly as possible.

- As the rabies virus can enter the body through a bite or scratch, it is crucial to remove as much saliva and, consequently, the virus, from the site using a trauma-free, effective wound toilet.

- It is necessary to thoroughly wash and flush the wounds for about 15 minutes using soap or detergent and lots of water. If soap and detergent are not immediately accessible, wash for 15 minutes under running water.

- It should be highlighted that cleansing the wound right away comes first. When a fresh wound is cleaned right away, the wound washing’s full benefits are realized.

- As the rabies virus can stay and even multiply at the site of the bite for a long time, a wound check must be conducted even if the patient reports late if the wounds are not healed.

- It is strongly advised against using local treatments on wounds.

- If any local irritants, such as herbs, oil, chili powder, or turmeric powder, have been administered, the wounds should be thoroughly washed to eliminate them.

- Local antiseptics (viricidal topical preparations), such as povidone-iodine, should be applied to wounds after washing.

Complications of Rabies

- Seizures

- Fasciculations

- Psychosis

- Aphasia,

- Autonomic instability

- Paralysis

- Coma

- Death

Prevention of Rabies

- Vaccinate your pets: to lower your risk of coming into contact with rabid animals. It is possible to vaccinate against rabies in cats, dogs, and ferrets. Ask your vet how frequently your pets should receive vaccinations.

- Keep your animals inside: Keep your pets indoors, and keep an eye on them if you let them out. By doing this, you can prevent your pets from encountering wild creatures.

- Keep little animals safe from predators: To keep them safe from wild creatures, keep guinea pigs and other small pets inside or in secure cages. These tiny animals cannot receive a rabies vaccination.

- Inform local authorities about stray animals- To report stray dogs and cats, contact your neighborhood’s animal control department or other local law enforcement.

- Do not let bats into your house: Fill in any openings or crevices where bats could enter your house. If you are aware that there are bats in your home, consult a local expert to come up with solutions to keep them out.

- Pre-exposure vaccination: If you frequently or when traveling around animals that may have rabies, you should think about being vaccinated. Consult a doctor about getting the rabies vaccine if you are going to be spending a lot of time in a country where rabies is prevalent.

Prognosis

- Post-exposure prophylaxis, or treatment after (getting the immunizations), is extremely effective in avoiding the illness if given early, typically within ten days of infection.

- PEP is 100% successful in preventing rabies when started with little to no delay. Even though there has been a sizable delay in starting PEP treatment, it should still be started because the medication might still work.

- When neurological symptoms appear in uninfected people, rabies usually proves lethal, but immediate post-exposure immunization may stop the virus’ spread.

- An estimated 55,000 individuals per year, predominantly in Asia and Africa, die from rabies.

- Even with therapy, survival rates for diseases after the onset of symptoms are low.

- Within 7 days of the onset of symptoms, respiratory failure frequently results in death.

Summary

- Rabies is a viral disease caused by a rabid animal biting or scratching a person or animal, it can transmit the viral disease rabies, which affects the central nervous system (CNS).

- About 59,000 people die from rabies each year in the world.

- The initial symptoms, which might include general weakness or pain, fever, or headache, can be quite like those of the flu.

- These symptoms can linger for days.

- The pathognomonic symptoms include hydrophobia and aerophobia, which affect 50% of victims.

- The direct fluorescent antibody (DFA) test, which looks for rabies viral antigens in brain tissue, is used to determine the presence of rabies in animals.

References

- Koury, R., Warrington, SJ. ( 2023, Jan ) Rabies. StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved on 20023 March 29 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448076/

- Gelbart, D. (2019). Rabies. JAAPA: official journal of the American Academy of Physician Assistants, 32(10), 46–47. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.JAA.0000580572.87216.17

- Liu, C., & Cahill, J. D. (2020). Epidemiology of Rabies and Current US Vaccine Guidelines. Rhode Island medical journal (2013), 103(6), 51–53.

- Jackson A. C. (2018). Rabies: a medical perspective. Rabies: a medical perspective. Revue scientifique et technique (International Office of Epizootics), 37(2), 569–580. https://doi.org/10.20506/rst.37.2.2825

- Denis, M., Knezevic, I., Wilde, H., Hemachudha, T., Briggs, D., & Knopf, L. (2019). An overview of the immunogenicity and effectiveness of current human rabies vaccines administered by intradermal route. Vaccine, 37(1), A99–A106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.11.072

- Acharya, K. P., Chand, R., Huettmann, F., & Ghimire, T. R. (2022). Rabies Elimination: Is It Feasible without Considering Wildlife?. Journal of Tropical Medicine.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, Dec 8). Rabies. Retrieved on 2023 March 28 from https://www.cdc.gov/rabies/index.html

- World Health Organization (2023, Jan 19). Rabies. Retrieved on 2023 March 29 from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/rabies