Introduction

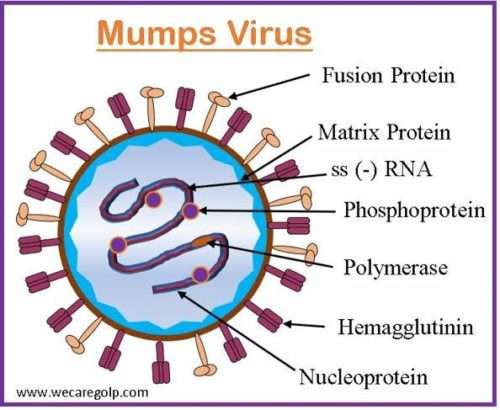

Mumps is a contagious viral infection caused by the Mumps virus, a single-stranded, linear, negative-sense RNA virus belonging to the Paramyxoviridae family and subfamily Rubulavirinae. During illness, the virus first infects the upper respiratory tract. From there, it spreads to the salivary glands and lymph nodes. The virus spreads throughout the body when it enters the bloodstream through a lymph node infection. The peak season for this infection is late winter and early spring.

- The mumps virus is extremely contagious, easily spreads in areas with high population densities, and only transmits among humans by respiratory droplets, direct contact with an infected individual, or fomite.

- The early symptoms, which commonly begin in childhood are fever, muscle discomfort, headache, loss of appetite, a general sensation of malaise, and parotitis.

- The patient’s face takes on a “hamster-like” appearance due to enlargement of the salivary glands, which is the most noticeable symptom.

- The illness is typically self-limited, and patients make a full recovery.

- When compared to other infectious disorders, mumps has received less attention due to their benign clinical presentation. Globally contagious mumps is the only recognized factor in pandemic parotitis.

- It can result in major complications and long-term health effects, such as hearing loss and infertility.

- The prevalence in the community has significantly decreased as a result of universal immunization.

Incidence

- Although rare outbreaks can happen at any time of year, the peak incidence of mumps normally occurs in late winter or early spring.

- Before the implementation of the mumps vaccination program, it was a serious illness that caused significant morbidity and mortality throughout the world.

- It is more common in school-age children and young adults who are in their early 20s, it is rare in infants under one year old who are protected by maternal antibodies.

- When the United States started its mumps vaccination program in 1967, there were roughly 186,000 cases reported annually. With 6584 instances in 2006, there was a comeback of mumps in the US, mostly affecting young adults who had had vaccinations in the past.

- Since then, intermittent outbreaks have caused the number of instances to fluctuate, from a low of 229 in 2012 to a peak of 6366 in 2016 and 6109 in 2017, mostly on college campuses and in other tight-knit communities.

Incubation Period

- The incubation period of the mumps ranges from 16 to 18 days. However, it can last between 12 to 25 days.

Causes of Mumps

- The mumps virus, an RNA-enveloped virus that belongs to the Orthorubulavirus genus in the Paramyxoviridae family of viruses, causes the mumps.

Risk Factors

The risk of contracting mumps is increased in some populations. The risk group includes

- Individuals with compromised immune systems

- Those who are not immunized against the mumps virus

- Residents in close quarters, such as those on college campuses

- Travelling to areas where the infection is widespread

- Coming into contact with a mumps sufferer

- Children between the ages of 2 and 12

Signs and Symptoms of Mumps

Many children exhibit no symptoms or perhaps very minor ones. The following are the most common mumps symptoms in adults and children:

- Enlarged and pain in the parotid glands or salivary glands

- Puffy cheeks and discomfort

- A swollen jaw

- Pain and tenderness in the testicles

- Exhaustion

- Loss of appetite

- Fatigue

- Weight loss

- Difficulty chewing

- Painful swallowing

Mode of transmission

The transmission time of the mumps is usually from a few days before the salivary glands begin to swell to up to five days after the swelling begins. There are three ways to spread it.

- Directly through contact with droplet nuclei

- By airborne droplets

- Through contaminated formatives such as items covered in bodily secretions

Pathophysiology of Mumps

- After exposure, the virus infects upper respiratory tract epithelial cells that have sialic acid receptors on their surface.

- The virus travels to the parotid glands after infection, resulting in recognizably visible parotitis.

- It is believed that the virus travels quickly to the lymph nodes after infection, particularly T-cells and viruses in the blood, known as viremia.

- During the 7–10 days of viremia, the mumps virus spreads throughout the body.

- The parotid gland is typically affected; however, other organs including the ovary, pancreas, testis, and epididymis may also be affected.

- The virus can once again be isolated from blood after the commencement of the illness, demonstrating that virus proliferation in target organs causes a secondary viremia.

- The most typical manifestation, which affects 95% of people with clinical symptoms, is parotitis.

- After a natural infection, the immunity lasts a lifetime, although reinfections can happen and are considered to account for 1 to 2 percent of all cases.

Diagnosis

- Medical history, including immunization status

- Physical examination

- A complete blood count (CBC) – It indicates a white blood cell (WBC) count that is normal, reduced, or raised, with lymphocytes predominating in the differential count.

- Inflammatory markers– Elevated levels of inflammatory markers in the serum can indicate a generalized inflammatory response.

- C-reactive protein (CRP)

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR)

- Amylase

- Increased amylase-S in mumps parotitis

- Increased amylase-P and serum lipase in pancreatitis

- Antibodies indicate the mumps infection

- A positive mumps-specific immunoglobulin M (IgM) titer or

- Evidence of a significant increase in mumps-specific immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody titers

- Hemagglutination inhibition, enzyme immunoassay, and complement fixation can all be used to measure IgG titers. Due to the potential for cross-reaction between the mumps virus and other parainfluenza viruses, the interpretation of the titer rise may be limited. The mumps virus can be isolated from

- Nasopharyngeal swabs,

- Blood, and

- Fluid from the buccal cavity.

- A lumbar puncture– To retrieve CSF (cerebrospinal fluid) for testing may be considered to determine the cause, if meningitis or encephalitis are suspected.

- Auditory testing– To determine whether a hearing impairment is developing, auditory testing is advised.

- Scrotal Ultrasonography-When orchitis is clinically suspected, scrotal ultrasonography must be done to rule out testicular torsion.

Treatment/Management of Mumps

Conservative, supportive medical treatment is advised for mumps patients. The control of symptoms and prevention of complications are the main goals of care, as there is no specific antiviral therapy for mumps.

- Pain relief is provided by acetaminophen. Pain and swelling can be relieved with ibuprofen. Never administer aspirin to children or teenagers under the age of 18. The risk of Reye’s syndrome is increased by this.

- Be sure to stay hydrated.

- Apply warm or cold packs topically to the painful area of the parotid to reduce swelling.

- Eat soft foods that are simple to chew.

- To reduce mouth pain and discomfort, acidic meals (such as tomatoes and food additives containing vinegar) and beverages (like orange juice) should be avoided.

- Patients with orchitis may need stronger analgesics in addition to bed rest, scrotal support, and cold packs. Mumps can be treated as an outpatient condition if there are no significant problems present.

- Steer clear of acidic foods and mouth-watering foods like citrus fruits.

- Many times a day, gargle with warm salt water.

- To relieve throat discomfort, try popsicles.

- Use an athletic supporter to hold the scrotum in place if your testicles are enlarged.

- Ice cubes could ease the pain.

- For at least five days after symptoms start, stay away from close contact with others and avoid public areas. To reduce the danger of spreading the disease to others, patients with mumps should remain home from work or school for five days after the onset of symptoms, preferably in a separate room.

Complications of Mumps

Mumps-related inflammation has the potential to spread to different parts of the body. The following are examples of mumps-related complications:

- Meningitis-10% of mumps patients get aseptic meningitis.

- Encephalitis– is a rare (0.02-0.3% of cases) consequence. Mumps encephalitis has a low case fatality rate, but it can have long-lasting effects, such as hydrocephalus, aqueductal stenosis, paralysis, convulsions, and cranial nerve palsies.

- Orchitis– 20% of post-pubertal boys with mumps also have orchitis, which is an inflammation of one or both testicles.

- Oophoritis– Girls who have entered puberty may experience breast inflammation (mastitis) or ovarian inflammation (oophoritis).

- Hearing loss– About 5 out of every 10,000 mumps patients get hearing loss because of cranial nerve involvement, particularly damage to the eighth cranial nerve.

- Pancreatitis- Around 4% of cases are reported to have pancreatitis as a side effect.

- Spontaneous abortions- A mumps infection during the first 12 weeks of pregnancy increases the risk of spontaneous abortions by 25%.

Prevention of Mumps

Vaccination

- The best way to lower the child’s risk of contracting the mumps is to vaccinate them against it.

- Measles, mumps, and rubella are the three diseases it is typically administered as part of a combination vaccine to prevent (MMR). MMR vaccinations for children should be given twice:

- The first dose: between 12 and 15 months of age

- The second dose: between 4 and 6 years

- The MMR vaccine is reliable and secure. Most kids don’t experience any negative side effects from immunization. The few side effects, like a fever or rash, are typically extremely minor.

Other Preventive Measures

- Individuals with mumps should avoid contact with other people for at least five days after their symptoms start.

- Compelled the patient to wash their hands properly.

- Encourage the patient to cover their mouth and nose while coughing and sneezing with a tissue (throw away used tissues) and, if none are available, to do so with their upper arm or elbow, not their hands.

- Patients should not let others use their drinking glasses or dining utensils.

- Surfaces that are frequently handled, such as toys, doorknobs, tables, and counters, should be kept clean.

Prognosis

- Most sufferers of mumps have a very good prognosis because death and long-term sequelae are quite uncommon.

- Usually, children with mumps make a full recovery in a few weeks.

- The sickness is more likely to be severe in adults who contract the mumps.

- Most of the time, hospitalization is not necessary.

- The symptoms typically disappear on their own in two weeks when the body’s immune system eliminates the virus from the body.

- The prognosis is thought to be the same for high-risk categories such as immune-compromised individuals.

- Most people develop lifelong immunity to future infections after contracting an infection.

- Compared to the initial illness, reinfections seem to be milder and more unusual.

- Only 1.6 to 3.8 per 10,000 cases have a case fatality with this infection, and typically, those who develop encephalitis have these deaths.

Summary

- Mumps is caused by a contagious virus called mumps virus.

- It can be transmitted through talking, sneezing, or coughing, and it frequently strikes children.

- The salivary glands enlarge after symptoms such as chills, headache, nausea, fever, and a general feeling of being unwell.

- Common symptoms are used to make the diagnosis.

- The majority of youngsters recover without any issues.

- Deafness, pancreatitis, inflammation of breast tissue, meningitis, and encephalitis are a few possible complications.

- Relieving symptoms is the main focus of treatment.

- Regular vaccinations can help ward off the disease.

References

- Su, S. B., Chang, H. L., & Chen, A. K. (2020). Current Status of Mumps Virus Infection: Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, and Vaccine. International journal of environmental research and public health, 17(5), 1686. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17051686

- Davison, P., Morris, J. (2023 Jan). Mumps. StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved on 2023, March 26 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534785/

- Gouma, S., Koopmans, M. P., & van Binnendijk, R. S. (2016). Mumps virus pathogenesis: Insights and knowledge gaps. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics, 12(12), 3110–3112. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2016.1210745

- Ramanathan, R., Voigt, E. A., Kennedy, R. B., & Poland, G. A. (2018). Knowledge gaps persist and hinder progress in eliminating mumps. Vaccine, 36(26), 3721–3726. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.05.067

- Grennan, D. (2019). Mumps. JAMA, 322(10), 1022. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.10982

- Centre for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021, March 8). Mumps. Retrieved on 2023, March 25 from https://www.cdc.gov/mumps/index.html

- Lam, E., Rosen, J. B., & Zucker, J. R. (2020). Mumps: an update on outbreaks, vaccine efficacy, and genomic diversity. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 33(2), e00151-19. DOI: 10.1128/CMR.00151-19