Introduction

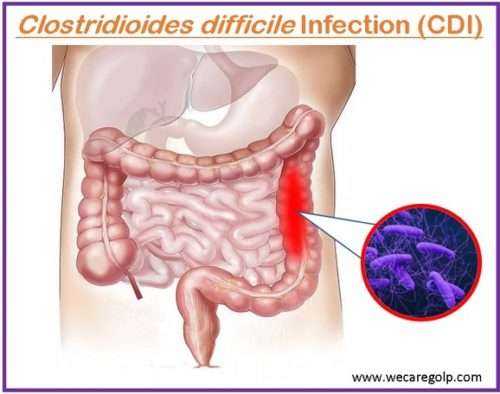

Clostridioides difficile infection (C. difficile, C. diff., or CDI), also called Clostridium difficile infection, is an infection caused by a gram-positive, spore-forming bacterium Clostridioides difficile.

C. difficile is an anaerobic, toxin-producing bacterium that causes antibiotic-associated colitis. It is a type of bacteria found in the intestines of many people which is a normal part of the body’s bacterial balance.

Bacterial spores spread Clostridium difficile infection through feces. Most people have no problems with C. difficile. However, the growth of C. difficile may be uncontrollable if there is unbalanced in the intestines. The bacteria begin to produce toxins that irritate and attack the lining of your intestines.

- Clostridium difficile colitis is caused by a disruption in the normal bacterial flora of the colon, colonization by C. difficile, and the release of toxins that cause mucosal inflammation and damage, showing off Clostridioides difficile infection symptoms. Alike in an E. coli infection, blood may present in the stools.

- Toxins A and B produced by C. difficile cause inflammation in the colon.

- CDI is one of the most common healthcare-associated infections and a leading cause of morbidity and mortality, particularly among hospitalized older adults.

- Antibiotic therapy is the primary factor influencing colonic flora. CDI mostly affects hospitalized patients.

- The severity of clinical illness ranges from mild diarrhea to fulminant colitis and death.

Incidence

- According to recent CDC estimates, approximately half a million Americans have CDI each year.

- Within a month of being diagnosed with C. difficile, approximately 29,000 patients have a fatal outcome, with 15,000 of these deaths directly attributable to the infection.

- Around 83,000 C. difficile patients experienced at least one recurrence, and within 30 days of the initial diagnosis, 29,000 people died.

- Most cases are acquired in the hospital.

- Community-acquired C. difficile colitis accounts for up to 40% of all cases.

Causes

- It is caused by toxigenic strains of Clostridium difficile (bacillus gram-positive, anaerobic).

- There are two types of C. difficile:

- Spore form: outside the colon; heat, acid, and antibiotic resistance

- Vegetative form: intestine; highly contagious.

- Spores spread via the fecal-oral route.

Risk factors

While anyone can become infected with C. difficile, certain people are at a higher risk.

- Recent antibiotic treatment – The risk increases with the duration and number of antibiotics used. Antibiotics that are most frequently implicated:

- Clindamycin,

- Cephalosporins,

- Fluoroquinolones, and

- Ampicillin.

- Proton-pump inhibitors (gastric-acid suppression)

- Advanced age > 65

- Medical comorbidities

- Hospitalization

- Gastrointestinal surgery

- Enteral feeding

- Obesity

- Chemotherapy

- Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- Cirrhosis

- Prior Clostridioides difficile infection

- A weakened immune system

Transmission

- Person-to-person spread from symptomatic patients either directly or indirectly via contaminated hands of healthcare/other care workers

- Via contact with environmentally contaminated surfaces e.g., commodes

- Spread does not occur from asymptomatic carriers.

Incubation Period

- Although the C. difficile incubation period is unknown, researchers believe it is around seven days if the conditions are favorable for bacterial proliferation.

- However, a person can get C. difficile and not get sick, but they will be colonized for a long time (years) until conditions that favor C. difficile proliferation develop.

- Infection can occur within 48 hours of exposure and up to three months after discharge.

Signs and Symptoms

Signs and symptoms usually appear 5 to 10 days after beginning an antibiotic course. They can, however, occur as early as the first day or as late as three months later. Infection ranges from mild to moderate.

Mild to moderate symptoms

- Watery diarrhea three or more times per day for more than one day

- Mild abdominal cramping and tenderness

Severe symptoms

- Watery diarrhea up to 10 to 15 times per day

- Severe abdominal cramping and pain

- Rapid heart rate

- Dehydration

- Low-grade fever of up to 101°F in children or 100°F to 102°F in adults

- Nausea

- An increased white blood cell count

- Kidney failure

- Loss of appetite

- Weight loss

- Blood or pus in the stool

- Sepsis (infection causes tissue damage)

- Colitis and the formation of raw tissue patches that can bleed or produce pus.

Pathophysiology

- The use of systemic antibiotics, such as broad-spectrum penicillin and cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, and clindamycin, alters the microbial flora of the large intestine, making it susceptible to CDI, and the disease is transmitted via the fecal-oral route.

- C. difficile colonizes the human large intestine.

- When an antibiotic kills off other competing bacteria in the intestine, the remaining bacteria have less competition for space and nutrients.

- The net result is that certain bacteria can grow more extensively than usual. C. difficile is one of these bacteria.

- C. difficile not only multiplies in the bowel but also produces toxins.

- Toxin A has a carbohydrate receptor binding site, which helps toxin A and toxin B transport intracellularly.

- Both toxins, once intracellular, cause the inactivation of pathways mediated by the Rho family of proteins, resulting in colonocyte damage, disruption of intercellular tight junctions, and colitis.

- A viscous collection of inflammatory cells, fibrin, and necrotic cells forms the “pseudomembrane” of severe infection in colitis.

Diagnosis

History collection

- Acute onset of diarrhea with no other explanations

- Antibiotic treatment within the previous three months

- Recent abdominal surgery

- Hospitalization

- Chronic medical conditions

Physical examination.

- Severe colitis

- Widespread abdominal tenderness or distention

- Tachycardia, hypotension, fever, and low urine output are signs of dehydration and sepsis.

Laboratory studies

The following laboratory tests are used to evaluate CDI patients:

- Complete blood count:

- Leukocytosis is possible (levels can reach dangerously high in severe infection).

- Levels of electrolytes, including serum creatinine: Severe disease may be accompanied by dehydration, anasarca, and electrolyte imbalance.

- Albumin levels: Hypoalbuminemia can occur in conjunction with severe disease.

- Lactate level in the blood: In severe disease, lactate levels are generally elevated (5 mmol/L).

- Stool examination:

- In severe colitis, blood may present in stools, but grossly bloody stools are unusual

- Fecal leukocytes are present in approximately half of the cases.

Stool assays for C. difficile

- Stool culture: The most sensitive test (sensitivity, 90–100%; specificity, 84–100%), but the results are slow and may cause a delay in diagnosis if used alone.

- Glutamate dehydrogenase enzyme immunoassay (EIA): This is a very sensitive test (sensitivity, 85–100%; specificity, 87-98%). It detects the presence of glutamate dehydrogenase produced by C. difficile.

- Real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay: This test is an alternative gold standard to stool culture (sensitivity 86%; specificity 97% [3]). It can detect the C. difficile gene toxin.

- Stool cytotoxin test: A positive test result indicates the presence of a cytotoxic effect that can be neutralized by a specific antiserum (sensitivity, 70–100%; specificity, 90–100%).

- EIA for detecting toxins A and B: This test is used in most laboratories (moderate sensitivity, 79–80%; excellent specificity, 98%).

- Latex agglutination technique: It is another method for detecting glutamate dehydrogenase; however, the sensitivity of this test is low (48–59%), while the specificity is high (95–96%).

Imaging examinations and procedures

- Abdominal X-ray:

- It shows colonic dilatation.

- It allows for free air if perforation occurs.

- CT scan

- It can detect colitis, ileus, or toxic megacolon.

- It can also reveal complications such as perforation.

- Endoscopy

- It may reveal raised, yellowish-white, 2- to 10-mm plaques overlying erythematous and edematous mucosa. These plaques are referred to as “pseudomembranes.”

- Endoscopic findings may be normal in patients with mild disease or may show nonspecific colitis in patients with moderate disease.

Treatment

A CDI is managed in a multi-step process that includes discontinuing inflaming antibiotics, isolating the patient, and administering the antibiotic based on the severity of the infection.

Medications

- Common antibiotics used to treat C. difficile infection include vancomycin and fidaxomicin. A patient who is asymptomatic despite a positive stool toxin test does not require treatment.

- Intravenous metronidazole can be used in patients suffering from ileus when orally administered antibiotics are delayed.

- Vancomycin cannot be administered intravenously because it is not secreted into the colon.

- According to new IDSA guidelines, an initial, non-severe CDI episode in adults can be treated with vancomycin 125 mg orally four times per day or fidaxomicin 200 mg twice a day for 10 days,

- Serum creatinine levels greater than 1.5 times, white blood cell count greater than 15,000 cells/microliter, and serum albumin less than 3 g/dL are all indicators of severe CDI. A severe first episode of CDI can be treated with the same dose of vancomycin or fidaxomicin as a non-severe first episode.

- Vancomycin, 500 mg, 4 times per day, orally or via NG tube, is used to treat an initial fulminant episode with hypotension, shock, ileus, or megacolon. If ileus exists, a rectal vancomycin enema (500 mg in 100 mL of normal saline per rectum, 4 times per day) can be used. Oral or rectal vancomycin can be combined with intravenous metronidazole 500 mg three times per day.

- If vancomycin was used for the initial episode, the first recurrence of CDI can be treated with a prolonged taper and pulsed vancomycin regimen of 125 mg, 4 times per day for 10 to 14 days, 2 times per day for 7 days, one time per day for 7 days, and finally, once every 2 to 3 days for 2 to 8 weeks, or fidaxomicin 200 mg, 2 times per day for 10 days.

- A second or subsequent recurrence can be treated with the same taper and pulsed vancomycin regimen described for the first recurrence: vancomycin 125 mg orally, 4 times per day for 10 days, followed by rifaximin 400 mg orally, 3 times per day for 20 days, and fidaxomicin 200 mg, twice daily for 10 days.

- Bezlotoxumab, a newer human monoclonal antibody against C. difficile toxin, is used to prevent the recurrence of CDI who are under treatment of CDI.

Probiotics

- Certain microbes with 7-dehydroxylase activity have been shown to metabolize primary to secondary bile acids, inhibiting C. difficile.

- Thus, incorporating such microbes into therapeutic products like probiotics may be beneficial.

Fecal microbiota transplantation

- A fecal microbiota transplant, also known as a stool transplant, is approximately 85%–90% effective in those who have not responded to antibiotics.

- It entails infusing microbiota derived from the feces of a healthy donor to correct the bacterial imbalance that causes the infection to reoccur.

- The procedure restores the normal colonic microbiota that was destroyed by antibiotics and re-establishes resistance to C. difficile colonization.

- In November 2022, the FDA approved live fecal microbiota (Rebyota) for medical use in the United States.

Surgery

- Certain fulminant colitis patients who develop complications such as toxic megacolon, intestinal perforation, and necrotizing colitis may necessitate surgical intervention such as a subtotal colectomy with rectum preservation.

Complications

The complications of a CDI include:

- Dehydration– Severe diarrhea can result in significant fluid and electrolyte loss. This makes it difficult for your body to function normally and can lead to dangerously low blood pressure levels.

- Kidney disease– Dehydration can occur so quickly in some cases that kidney function rapidly deteriorates (kidney failure).

- Toxic megacolon– In this uncommon condition, the colon is unable to expel gas and stools, causing it to swell significantly (megacolon). The colon may rupture if left untreated. Bacteria from the colon may then enter your stomach or bloodstream. A toxic megacolon can be fatal and necessitates immediate surgery.

- A bowel perforation (an obstruction in your large intestine)– This condition occurs as a result of extensive damage to the colon lining or after a toxic megacolon. Bacteria from the colon can cause a potentially fatal infection in the abdominal cavity (peritonitis).

- Death– If not treated promptly, a mild to moderate CDI can progress to a serious infection leading to death.

Prevention

Hospitals and other healthcare facilities must follow strict infection-control guidelines to help prevent the spread of C. difficile.

Antimicrobial stewardship

- Antimicrobial stewardship programs (ASPs) work to ensure that patients receive the appropriate antimicrobial for the indication, at the appropriate dose, and at the appropriate time.

- ASPs not only improve the efficacy of antimicrobial therapies, but they also limit the unnecessary use of antimicrobials, preserving the normal microbial flora or microbiome.

- The preservation of the gut microbiome is the best host defense for preventing C. difficile acquisition and colonization from becoming a symptomatic disease.

Hand-washing and protective accessories

- Before and after treating each person in their care, healthcare workers should practice good hand hygiene.

- Because alcohol-based hand sanitizers do not effectively destroy C. difficile spores, soap and warm water are a better choice for hand hygiene in the event of a C. difficile outbreak.

- Visitors should also wash their hands with soap and warm water before entering and leaving the room or using the restroom.

- Gloves have been shown to reduce CDI significantly but do not completely prevent hand contamination. When dealing with CDI patients, current guidelines recommend the use of both gloves and gowns.

Isolation

- Isolating patients with infectious diarrhea as soon as possible is a well-established infection control intervention.

- As soon as CDI is suspected, patients should be isolated in a single room with a toilet or dedicated commode.

- Confirmed cases should be isolated for 48 hours if no diarrhea or formed stool has occurred.

- As part of broader infection control interventions, isolation measures have been effective in controlling CDI outbreaks.

Cleaning the environment

- Environmental sampling of CDI patients’ surroundings revealed high levels of contamination, especially on the floors, bedrails, commodes, fomites, and medical equipment.

- Increased contamination correlates with increased C. difficile carriage on the hands of healthcare workers.

- Because the spores are resistant to conventional cleaning agents (for example, detergents), sporicidal agents such as sodium hypochlorite (bleach) or hydrogen peroxide vapor are recommended for effective decontamination.

- Several studies have shown that cleaning with hypochlorite at a concentration of at least 1,000 ppm is effective in lowering CDI rates.

Prognosis

- Some patients with C. difficile colitis may recover without treatment; however, persistent diarrhea can be debilitating and last for several weeks.

- After successfully completing therapy, approximately 20–27% of patients treated experience a first episode of C. difficile colitis relapse, typically 3 days to 3 weeks later.

- Patients who relapse once are more likely to relapse again; the relapse rate for patients with two or more relapses is 65%.

- Treatment failure, the development of severe-complicated infection, sepsis and the need for intensive care unit admission, the need for colectomy, an increased length of hospital stay, and mortality are all adverse outcomes of Clostridium difficile infection.

- The overall mortality rate from pseudomembranous colitis ranges from 4.9% to 6.2%.

Summary

- Clostridioides difficile infection is caused by the spore-forming bacterium Clostridioides difficile.

- Watery diarrhea, fever, nausea, and abdominal pain are some of the symptoms.

- Bacterial spores found in feces are the main source of CDI.

- Antibiotic or proton pump inhibitor use, hospitalization, other health problems, and advanced age are all risk factors for infection.

- Diagnosis is accomplished through stool culture or testing for the bacteria’s DNA or toxins.

- Pseudomembranous colitis, toxic megacolon, colon perforation, and sepsis are all possible complications.

- Prevention efforts include terminal room cleaning in hospitals, limiting antibiotic use, and hospital handwashing campaigns.

- Discontinuation of antibiotics may result in symptom resolution within three days in about 20% of those infected.

- The antibiotics vancomycin or fidaxomicin and metronidazole are the preferred drugs to cure the infection.

- C. difficile is a significant public health concern and should be managed on time to prevent it from worsening.

References

- McDonald, L. C., Gerding, D. N., Johnson, S., Bakken, J. S., Carroll, K. C., Coffin, S. E., Dubberke, E. R., Garey, K. W., Gould, C. V., Kelly, C, Loo, V, Sammons, J. S., Sandora, T. J., Wilcox, M. H. (2018, Apr 1). Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults and children: 2017 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA). Clinical infectious diseases, 66(7), e1-e48. doi.org/10.1093/cid/cix1085

- Nwachuku, E., Shan, Y., Senthil-Kumar, P., Braun, T., Shadis, R., & Vu, T. Q. (2021, Jan). Toxic Clostridioides (formerly Clostridium) difficile colitis: No longer a diarrhea associated infection. The American Journal of Surgery, 221(1), 240-242. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2020.06.026

- Kelly, C. R., Fischer, M., Allegretti, J. R., LaPlante, K., Stewart, D. B., Limketkai, B. N., & Stollman, N. H. (2021, Jun). ACG clinical guidelines: prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of Clostridioides difficile infections. Official journal of the American College of Gastroenterology| ACG, 116(6), 1124-1147. doi.org/10.14309/ajg.0000000000001278

- Guh, A. Y., & Kutty, P. K. (2018). Clostridioides difficile infection (Japanese version). Annals of internal medicine, 169(7), JITC49-JITC64. doi.org/10.7326/AITC201810020

- De Roo, A. C., & Regenbogen, S. E. (2020). Clostridium difficile infection: an epidemiology update. Clinics in Colon and Rectal surgery, 33(02), 049-057. doi.org/10.1055/s-0040-1701229

- Czepiel, J., Dróżdż, M., Pituch, H., Kuijper, E. J., Perucki, W., Mielimonka, A., Goldman, S., Wultanska, D., Garlicki, A., & Biesiada, G. (2019). Clostridium difficile infection. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases, 38, 1211-1221. doi.org/10.1007/s10096-019-03539-6

- Lamont J.T., Kelly C.P., Bakken J.S. (2022, Nov 22). Clostridioides difficile infection in adults: Clinical manifestations and diagnosis. Retrieved on 2023, Feb 11 from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clostridioides-formerly-clostridium-difficile-infection-in-adults-clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis