Introduction

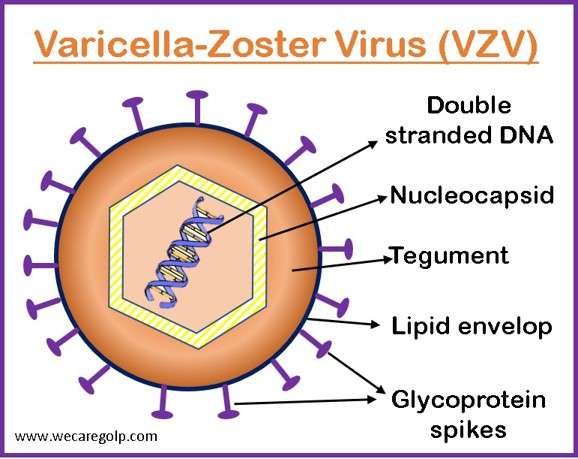

Chickenpox is a highly contagious disease caused by the Varicella-zoster virus (VZV). VZV is a Herpesviridae-family, linear, double-stranded DNA virus. These viruses spread through aerosolized respiratory droplets or contact with infected skin lesions and infect many tissues during primary infection before becoming dormant. They can reactivate later to cause disease.

- Chickenpox is primarily a childhood disease, with over 90% of cases occurring in children under the age of ten.

- It usually starts with mild constitutional symptoms and is quickly followed by painful skin lesions that are characterized by macules, papules, vesicles, and crusting primarily on the chest and abdomen.

- Most people who get chickenpox have mild symptoms and recover quickly. In rare cases, like certain underlying medical conditions and immunocompromised patients, the virus can cause serious complications such as pneumonia or meningitis.

- Once the symptoms have subsided, the virus remains dormant in the body and can reactivate as shingles later in life.

- Although antiviral medication may be administered to some patient populations, management is supportive.

- After contracting chickenpox, lifetime immunity is developed in the body.

- It is a preventable disease by vaccination.

- The FDA has approved the use of the live varicella virus vaccine to provide immunity for the prevention of varicella in people 12 months of age and older.

Incidence

- According to national seroprevalence data from the pre-vaccine era, less than 2% of adults in the United States were vulnerable to infection, while more than 95% of people in the country contracted varicella before the age of 20.

- Prior to 1995, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimated that there were four million cases of chickenpox annually in the US, leading to over 11,000 hospitalizations and 100 fatalities.

- Since 1995, when broad pediatric immunization was implemented in the United States, the incidence of varicella has decreased considerably, perhaps by as much as 90%., with mortality falling by roughly 66%.

- There is a higher frequency in nations with tropical and semitropical climates.

- Every country experience varicella, which results in roughly 7,000 deaths a year.

- It is a frequent illness among children in temperate regions, with most cases occurring in the winter and spring.

- It causes more than 9000 hospital admissions per year in the US.

- The age ranges from 4 to 10 years old and has the highest incidence. The prevalence of varicella infection is 90%.

- Adults tend to have deeper pockmarks and more visible scars.

Incubation period

- After exposure, the incubation period lasts from 10 to 21 days.

- The incubation period may be extended (e.g., up to 28 days or more) in those who received varicella-specific immune globulin post-exposure prophylaxis.

- Infectivity lasts 1-2 days before the rash appears until the blisters dry up, which usually takes about a week.

Causes

- The varicella-zoster virus (VZV) causes the disease.

Risk Factors of Chickenpox

The following groups are more vulnerable to contracting chickenpox.

- Close contact with someone who has chickenpox or shingles

- Sharing personal items or eating utensils with a person who has chickenpox

- Being a person of any age who has never had chickenpox before or who has not received the chickenpox vaccine

- Newborns, especially those born prematurely, under one month old, or whose mothers had never had chickenpox prior to pregnancy

- People with cancer

- Pregnant women

- People taking immunosuppressive medications

- People who are moderately or seriously ill but have not yet fully recovered

- People with certain blood, bone marrow, or lymphatic system disorders.

Mode of Transmission

Chickenpox is the illness that spreads most easily and transmits from one person to another through

- Direct contact with blister fluid

- Direct contact with respiratory secretions

- Handling contaminated clothing or bedding

- Exposure to an infected person’s airborne coughing or sneezing

- Touching or inhaling virus particles from chickenpox blisters contract the disease.

Signs and Symptoms of Chickenpox

The prodromal phase

- Feeling lethargic or ill overall (malaise)

- A fever lasts three to five days and typically is not higher than 102 °F (39 °C).

- Loss of appetite

- Aches in joints or muscles

- A headache; cold-like symptoms such as a cough or runny nose

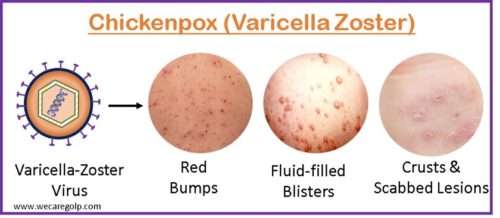

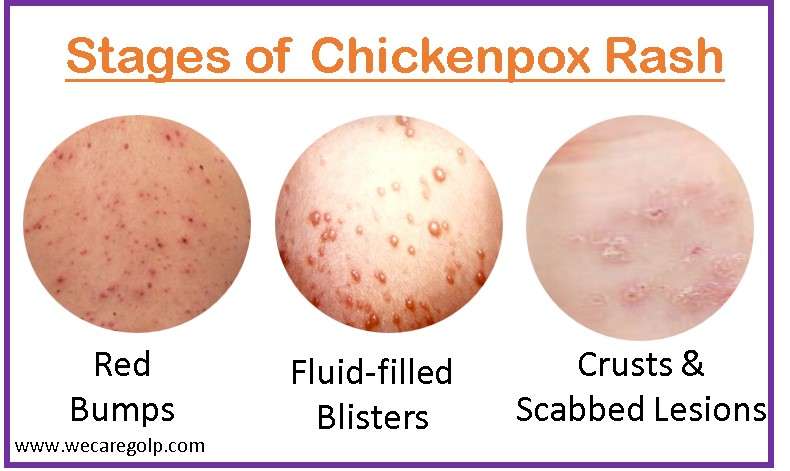

Rash and blister stage

- It can start as soon as 10 days after exposure.

- At this stage, the virus becomes visible on the epidermis.

- The rash frequently develops first on the trunk, back, and face before spreading across the entire body.

- Fluid-filled blisters are compared to a “dew drop on a rose petal.”

- The blisters appear symmetrical, brilliant, and nearly transparent.

- People frequently experience a low-grade fever during this phase.

Scabbing stage

- Scabbing occurs with chickenpox blisters.

- The sores harden over as they heal, and blisters pop open.

- Sores show up as dry, crusty scabs.

Pathophysiology of Chickenpox

- Inhaling airborne respiratory droplets from an infected host is often how chickenpox is contracted.

- The virus infects the upper respiratory tract’s conjunctivae or mucosa after the initial inhalation of contaminated respiratory droplets.

- 2-4 days after the initial infection, local lymph nodes of the upper respiratory tract show viral growth, which is followed by primary viremia on days 4-6 after the infection.

- The body’s internal organs, particularly the liver and spleen, undergo a second cycle of viral replication, which is followed by secondary viremia 14–16 days after infection.

- This secondary viremia is characterized by a widespread viral invasion of the epidermis and capillary endothelial cells.

- Intercellular and intracellular edema are produced when VZV infects cells in the Malpighian layer, resulting in the distinctive vesicle.

- When a healthy youngster is exposed to VZV, host immunoglobulin G (IgG), immunoglobulin M (IgM), and immunoglobulin A (IgA) antibodies begin to be produced; IgG antibodies last a lifetime and provide immunity.

- VZV spreads from mucosal and epidermal sores to nearby sensory nerves after primary infection.

- VZV then stays dormant in the sensory nerves’ dorsal ganglion cells.

- Herpes zoster is a clinically unique syndrome brought on by VZV reactivation (shingles).

Diagnosis of Chickenpox

Clinical analysis

- Typical rashes are the starting point for the diagnosis of chickenpox. The rash could be mistaken for other viral skin illnesses.

- If there is any ambiguity regarding the diagnosis, laboratory confirmation can be performed. It requires one of the following:

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) testing

- The use of PCR to detect VZV in skin lesions is the most accurate way to confirm a diagnosis of varicella (vesicles, scabs, and maculopapular lesions)

IgM testing

- A positive IgM ELISA result, although suggestive of primary infection, does not rule out re-infection or reactivation of latent VZV.

- IgM testing is significantly less sensitive than PCR testing of skin lesions.

Acute and convalescent sera

- Although they are less sensitive than PCR of skin lesions, paired acute and convalescent serums showing a four-fold elevation in IgG antibodies have great specificity for varicella.

Blood analysis

- Leukopenia and leukocytosis are typically present in children with varicella in the first three days. However, this is not always the case.

- In addition, 20–50% of children and adolescents with varicella complicated by hepatitis experience significant elevations of alanine aminotransferase (ALT), which almost always subside within a month.

Tzanck smear

- When performing a Tzanck smear, the base of the lesions is scraped, and the scrapings are stained to show multinucleated large cells.

- The presence of these cells not only indicates a herpes virus infection but also suggests varicella-zoster virus.

Staining with immunohistochemistry

- Varicella can be determined by immunohistochemical staining of scrapings from skin lesions.

Treatment/Management of Chickenpox

There is no specific treatment for children. However, symptomatic management can help relieve chickenpox symptoms. Children with chickenpox might receive oral and topical treatments for their symptoms.

Antiviral treatment

- The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) advises the use of antiviral drugs like acyclovir or valacyclovir for individuals who are more likely to get fatal conditions, e.g.,

- Children older than 12 years

- Those with chronic pulmonary or cutaneous conditions

- Those who are on long-term salicylate therapy

- Kids who are receiving corticosteroids

- Pregnant women

- Immunocompromised patients

Varicella–zoster immunoglobulin (VZIG)

- Within 10 days (preferably within 4 days) of exposure to chickenpox, it is recommended for high-risk individuals.

- This medication lowers the complications and death rate associated with varicella but not its incidence.

Antibacterial treatment

- Until the results of culture studies are known, empirical antibiotic therapy should be instituted as soon as a secondary bacterial infection is suspected.

Supportive treatment

- Rest

- Pain relief, such as paracetamol to reduce fever

- Lotions like calamine, which are sold at pharmacies, can be used to alleviate itching.

- Tepid baths with sodium bicarbonate, raw oatmeal, colloidal oatmeal, or treatments containing Pinetarsol can also help relieve itching.

- Provide soft food and cool liquids because the mouth and throat may be affected.

- Children’s fingernails should be kept short or covered with gloves to prevent infection of the sores. They should also wash their hands frequently with antibacterial soap.

- Avoid scratching to help prevent skin infections and prevent the virus from spreading to others.

- Put the patient in a pajama or light, loose-fitting clothing to prevent from the worsening of itching due to overheating and garment friction.

- Antihistamines to help with itching relief, such as diphenhydramine

- Aspirin should not be given to children with chickenpox because this has been linked to Reye’s illness, a rare condition that affects the liver and brain.

Complications of Chickenpox

Newborns, adults, those with compromised immune systems, and those with specific illnesses are more likely to experience a complication of chickenpox.

- Secondary bacterial infection; Cellulitis or, less frequently, necrotizing fasciitis or streptococcal toxic shock may result from a secondary bacterial infection (usually streptococcal or staphylococcal) of the vesicles.

- Pneumonia: In adults, newborns, and immune-compromised patients of all ages, pneumonia may exacerbate severe chickenpox.

- Hepatitis

- Hemorrhagic problems

- Myocarditis

- Post-infectious cerebellar ataxia

- Transverse myelitis

- Reye syndrome (liver and brain damage): It is an uncommon but severe childhood consequence and might appear 3 to 8 days after the rash first appears, usually after taking aspirin.

- Encephalitis, meningitis

- Permanent skin scarring

- Death (rare)

Prevention of Chickenpox

- Eighty to ninety percent of people who receive the chickenpox vaccine are protected from contracting the disease.

- Those who receive the vaccine but do not fully recover from it may contract chickenpox if exposed. Nonetheless, the disease is typically not severe, results in a less severe rash, and frequently have no fever.

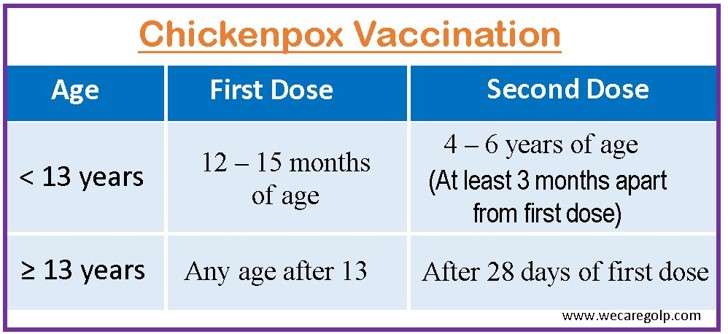

Vaccine for children

- The varicella vaccine is advised for all infants between the ages of 12 and 15 months.

- Between the ages of 4 and 6, a second dose is advised.

- The second dosage may be delivered sooner than age 4 (for instance, during a varicella outbreak) but it should be given at least three months apart.

- The vaccination can be administered either by single chickenpox vaccine (Varivax) or in a mixture that includes the measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella vaccines (MMRV, ProQuad).

- If a child contracts chickenpox before receiving the varicella vaccination, it is not necessary for them to receive it.

Vaccine for adult

- Individuals who have already experienced chickenpox are resistant to varicella infection.

- Those who do not already have chickenpox immunity, however, can benefit from vaccination.

- For people over the age of 13, the two doses should be given at least 28 days apart, who do not have chickenpox vaccine or chickenpox infection.

- Specialists advise individuals without immunity to get vaccinated against varicella, especially those who are at risk of exposure to chickenpox.

- Healthcare workers

- Immune system-compromised individuals, such as

- Transplant recipients

- HIV-positive individuals

- Young children’s teachers Daycare staff

- Military bases or prisons

- International travelers

- Women of childbearing age

Other preventive measures

- Maintaining good cleanliness and routinely washing your hands can help stop the spread of chickenpox.

- Avoid or limit contact with people who have chickenpox.

- If you already have chickenpox, stay at home until all your blisters have dried out and crusted over.

Chickenpox and Pregnancy

- For pregnant women and their unborn children, chickenpox is especially harmful.

- First-time cases of chickenpox in pregnant women increase the risk of significant sickness and complications.

- In addition to severe chickenpox, babies of pregnant chickenpox sufferers may also be born with skin, eye, arm, limb, or nervous system birth abnormalities.

- See your doctor if you are considering becoming pregnant for guidance on pre-conception chickenpox immunity testing and to request a vaccination.

- It is advisable to acquire the chickenpox vaccine before becoming pregnant because it is contraindicated during pregnancy.

- When a pregnant woman is exposed to the virus, she cannot get the varicella vaccination; instead, she may need to get an injection called varicella zoster immune globulin (variZIG), which can help protect against infection.

- Women who contract chickenpox while pregnant need to be constantly watched for any problems or signs of infection.

- A substantial mortality rate has been linked to maternal chickenpox up to 48 hours postpartum and within five days of delivery.

Prognosis

- Healthy youngsters almost always experience a smooth recovery from chickenpox.

- Before widespread vaccination, approximately 4 million Americans contracted chickenpox each year, and 100 to 150 of them per year passed away from complications related to the disease.

- Chickenpox is more dangerous and deadly in adults because of its severity.

- These skin infections are typically moderate, but occasionally they can be more serious and affect the muscles and tissues beneath the surface.

- Sometimes, the rash can affect the brain as well.

- Morbidity is higher in adults and immune-compromised people.

- When those who have received the vaccine contract chickenpox, the illness is milder and there are fewer fatalities.

Summary

- Chickenpox is a typical childhood disease caused by the VZV.

- A red, itchy rash with fluid-filled blisters is the most typical sign of chickenpox.

- Children typically experience minimal symptoms.

- Adults and those of any age with weakened immune systems may find them to be life-threatening.

- The rash’s appearance and a history of exposure may typically be used to make the diagnosis.

- Most chickenpox cases are mild and go away on their own.

- The management is supportive, but antiviral medication may be beneficial in some patient populations.

- Encephalitis, pneumonia, or other bacterial infections are examples of complications.

- The varicella-zoster vaccine is recommended as a preventative strategy in young children.

References

- Ayoade, F., Kumar, S. (2022, Jan). Varicella Zoster (Chickenpox). StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved on 2023, Feb 19 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448191/

- Britannica. (2022, Nov 20). Chickenpox. Retrieved on 2023, Feb 20 from https://www.britannica.com/science/chickenpox

- Lo Presti, C., Curti, C., Montana, M., Bornet, C., & Vanelle, P. (2019). Chickenpox: An update. Medecine et maladies infectiouses, 49(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medmal.2018.04.395

- Kota, V., Grella, MJ. (2022 Feb 4). Varicella (Chickenpox) Vaccine. StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved on 2023, Feb 19 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441946/

- Center for Disease Control and prevention. (2022 Oct 11). Chickenpox (Varicella). Retrieved on 2023, Feb 20 from https://www.cdc.gov/chickenpox/about/index.html

- Health direct. (2021, Nov). Chickenpox (Varicella). Retrieved on 2023, Feb 19 from https://www.healthdirect.gov.au/chickenpox