Introduction

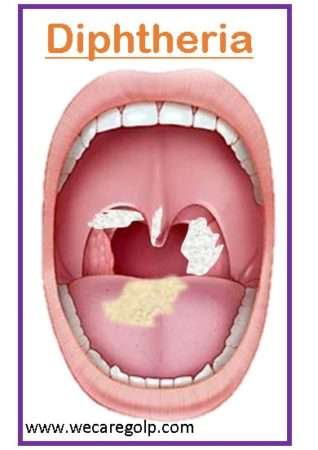

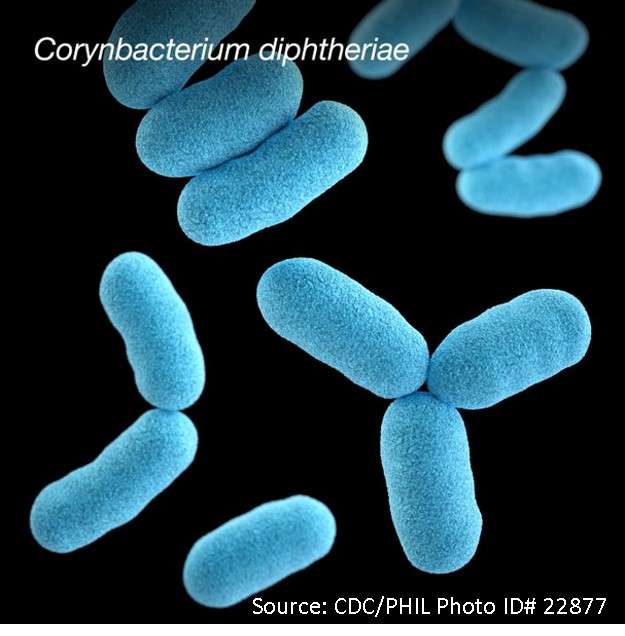

Diphtheria is a contagious infection caused by Corynebacterium diphtheriae, a non-encapsulated, non-motile, Gram-positive bacillus bacterium. The bacteria infect and multiply in the airways, releasing a dangerous toxin that can harm major organs. The formation of the pseudo membrane on the site of colonization is a defining feature of the disease. The most common sites of involvement are the anterior tonsillar pillars and posterior pharyngeal walls.

- The specific diphtheria bacillus produces a toxin that destroys tissues and membranes before being absorbed into the bloodstream and distributed throughout the body.

- The anatomic site of infection, the host’s immune status, and the production and systemic distribution of toxins all influence the clinical manifestations of C. diphtheria infection.

- Pathogenic strains can cause severe upper respiratory infections, localized cutaneous infections, and, in rare cases, systemic infections.

- Diphtheria is a severe communicable and bacterially infectious disease that causes inflammation of the mucous membranes in the throat, causing difficulty swallowing food and breathing. The bacterial toxin present in the blood can also cause nerve damage.

- This disease is easily transmitted from person to person, but it can be avoided by using vaccines. It primarily affects the upper respiratory tract, including the tonsils, nose, and throat.

- The case fatality rate for this disease is 10%.

Incidence

- Before the vaccine, 100,000-200,000 cases and 13,000-15,000 deaths were reported annually.

- Cases rapidly declined after the introduction of the universal vaccination program in the late 1940s, 14 cases and 1 death were reported in the United States from 1996 to 2018.

- A total of 8,819 cases of diphtheria were reported worldwide in 2017, the most since 2004.

- Diphtheria was once a leading cause of childhood death worldwide, but cases have been dramatically reduced in recent decades due to mass vaccination campaigns followed by routine childhood vaccination.

- Although high-income countries rarely see cases, low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where the disease remains endemic.

- Diphtheria is especially likely to reemerge in areas where there is overcrowding, inconsistent vaccination, and a lack of public health infrastructure to treat cases and prevent further spread.

Classification of Diphtheria

Diphtheria is classified based on the site of infection.

Nasal Diphtheria

- It is distinguished by a purulent nasal discharge that can become blood-tinged and a white membrane that can form in the nasal septum.

- Isolated nasal diphtheria is uncommon and usually mild.

Pharyngeal and Tonsillar Diphtheria

- The small white patches appear and grow, forming a grayish-white adhering membrane that can cover the entire pharynx, including the tonsils, uvula, and soft palate.

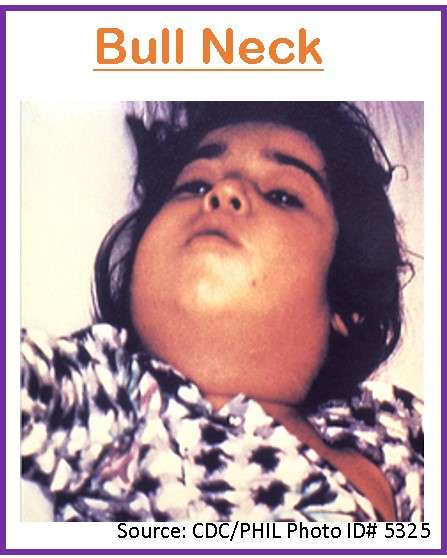

- Bleeding occurs when the membrane is attempted to be removed. The so-called “bulimia neck,” which is indicative of severe infection, is caused by edema and inflammation of the surrounding soft tissues.

- If left untreated for a week, the membrane softens and sloughs off in pieces or as a single block. As the membrane falls off, systemic symptoms begin to fade.

Laryngeal Diphtheria

- It can be isolated (the pharyngeal lesion does not develop) or an extension of the pharyngeal form.

- It is more common in children under the age of 4, and symptoms include gradually worsening hoarseness, barking cough, and stridor. It can cause pharyngeal obstruction and even death.

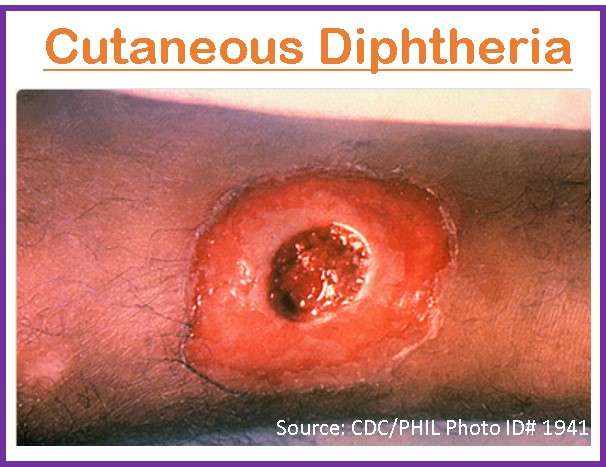

Cutaneous (Skin) Diphtheria

- The rarest type of diphtheria is distinguished by a skin rash, sores, or blisters that can appear anywhere on your body.

- It is a mild skin infection caused by either toxin-producing or non-toxin-producing bacilli.

- It is more common in the tropics and has frequently been linked to poverty and overcrowding.

- Individuals infected with cutaneous diphtheria can spread the disease to others.

Causes of Diphtheria

- Diphtheria is an infectious disease that occurs due to C. diphtheria, an anaerobic, Gram-positive, non-motile, non-spore-forming, non-capsulated, toxin-producing, pleomorphic coccobacillus.

- The toxin produced by this bacterium is what makes people sick.

Risk factors of Diphtheria

Common risk factors for the development of diphtheria include:

- Lack of immunization

- A history of contact with diphtheria patients

- Presence of skin lesions

- Presence of eczema

- A history of chronic health conditions

- Travel history to diphtheria-endemic areas

- Overcrowding

- Exposure to poor sanitary conditions

- Poor personal hygiene

- Sharing utensils and food with diphtheria-infected people

- The presence of tonsils

- Pre-school and school-age children are most affected by respiratory diphtheria

- Handling infected dairy animals and consuming contaminated milk.

Mode of Transmission

- Transmission occurs through respiratory droplets or contact transmission from an infected host or their carrier.

- It can also be transmitted through direct contact with objects or secretions that have previously been in contact with the infected person.

- The disease is present all year, with the highest prevalence during the colder months.

- After recovering from an illness, up to 5% of healthy people may have bacteria in their oropharynx. This is an asymptomatic carrier that transmits diphtheria.

Incubation period

- Diphtheria has an incubation period of 2 to 5 days, with a range of 1 to 10 days.

- Organisms can be found in the discharges and lesions of untreated people for 2 to 6 weeks after infection.

- A person is infectious for as long as virulent bacteria are present in respiratory secretions, which is usually two weeks in the absence of antibiotics and rarely more than six weeks.

Signs and Symptoms of Diphtheria

Diphtheria most commonly affects the respiratory tract, but it can affect any mucosal membrane. The disease appears gradually, with nonspecific and mild symptoms and signs.

Nasal Diphtheria

- Infection of the anterior nares

- Purulent, serosanguineous, erosive rhinitis with membrane formation.

- Shallow ulceration of the external nares and upper lip.

- Unilateral nasal discharge.

Tonsillar and pharyngeal diphtheria

- Sore throat (the most common early symptom)

- Fever (50% of patients)

- Dysphagia

- Hoarseness

- Malaise, or headache; mild pharyngeal infection

- Unilateral or bilateral tonsillar membrane formation extends to involve the uvula, soft palate, posterior oropharynx, hypopharynx, or glottic areas

- Underlying soft tissue edema

Laryngeal diphtheria

- Suffocation is a significant risk due to local soft tissue edema and

- Airway obstruction by the diphtheritic membrane.

Cutaneous diphtheria

- Pain, swelling, and redness of the site.

- Ecthymic, superficial, non-healing ulcer with a gray-brown membrane.

Other Sites of Infection

- Ear infection (otitis externa)

- Eye infection (purulent and ulcerative conjunctivitis),

- Genital tract infection (purulent and ulcerative vulvovaginitis)

- Sporadic cases of pyogenic arthritis.

Pathophysiology

- Susceptible individuals may acquire toxigenic Diphtheria bacilli in the nasopharynx.

- The organism produces a toxin that inhibits cellular protein synthesis and is responsible for local tissue destruction and the formation of the pseudo membrane that is characteristic of this disease.

- Through ADP-ribosylation, diphtheria exotoxin renders elongation factor (EF-2) inactive. This bacteriophage, a beta prophage, enters the host organism’s cells and DNA, resulting in the encoding of diphtheria exotoxin.

- The exotoxin has three domains: one for catalysis in fragment A, and two for receptor binding, membrane insertion, and translocation in fragment B.

- Because it ribosylates ADP in the elongation factor, exotoxin is the primary cause of diphtheria. The elongation factor, specifically elongation factor 2 (EF-2), is required for protein chain elongation. Diphtheria exotoxin inhibits EF-2, preventing protein synthesis and causing cellular death and secondary clinical manifestations.

- The toxin produced at the membrane site is absorbed into the bloodstream and distributed to the body’s tissues.

- The toxin is responsible for serious complications such as myocarditis, polyneuropathies, and nephritis, and it can also cause thrombocytopenia.

- Nontoxigenic C. diphtheriae infection can also cause cutaneous lesions, endocarditis, bacteremia, and septic arthritis.

Diagnosis of Diphtheria

History

- Typical age group (15 years or older)

- Exposure to infected individuals

- Travel to endemic regions

- Unvaccinated or inadequately vaccinated individuals

Physical Examination

- Fever, sore throat, malaise, cervical lymphadenopathy, headache, and dysphagia were all observed during the physical examination.

Laboratory Diagnosis

- Bacteriologic testing

- It involves staining a smear of the throat sample with Gram stain and methylene blue. Although Gram-staining does not confirm a diagnosis, it is the first test performed in suspected cases.

- The Gram-stain shows clusters of club-shaped, non-motile, nonencapsulated bacilli. The typical metachromatic granules are revealed by the methylene blue stain.

- Culture

- The throat swab is cultured on Loffler medium or Tindale medium, a telluride plate, and blood agar.

- A black colony with halos on Tindale medium, metachromatic granules on Loffler medium, and the typical gray-black color of tellurium indicate the organism’s presence in these media.

- Toxin testing

- In the case of C. diphtheriae, toxin detection aids in distinguishing toxigenic strains from non-toxigenic variants.

- This test includes Elek test, PCR test, and Enzyme Immunoassay (EIA) testing.

- Complete blood count: A complete blood count may reveal moderate leukocytosis.

- Troponin I: This helps determine the extent of myocardial injury.

Imaging Research

- An x-ray of the chest and neck may show swelling of the soft tissue structures in and around the pharynx, epiglottis, and chest.

Treatment of Diphtheria

- Antitoxins and antibiotics are the two most important treatment modalities for diphtheria.

- Aside from these two, the patient should be evaluated for respiratory and cardiovascular instability.

- When a patient is suspected of having diphtheria, antitoxin should be administered clinically rather than waiting for laboratory confirmation.

- Suspected cases must be kept in isolation, and proper droplet precautions must be implemented.

- Furthermore, the patient should be evaluated for respiratory distress, and if necessary, a definite airway should be secured.

- Cardiac monitoring is also an important part of early management.

Antitoxin

- Antitoxin is the mainstay of therapy and should be administered when diphtheria is suspected.

- It is administered as a single empirical dose of 20,000–120,000 U based on the degree of toxicity, location and size of the membrane, and duration of illness.

- The hypersensitivity test must be done before administering the antitoxin, and emergency anaphylaxis drugs must be kept at the bedside.

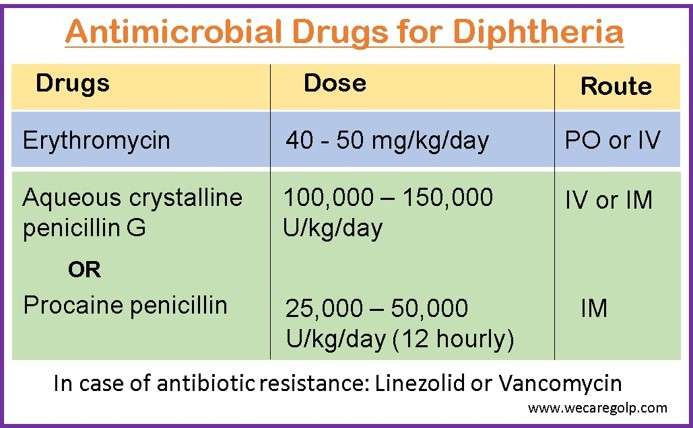

Antimicrobial Therapy

It halts toxin production, treats localized infection, and prevents organism transmission to contacts.

Complications

Diphtheria can cause the following complications:

- Myocarditis: It is an inflammatory disease of the heart muscle caused by infections with cardiotropic viruses, particularly coxsackievirus infections.

- Arrhythmias: A condition of heart rate or rhythm disturbances in which the heart beats too fast, too slowly, or in an irregular rhythm. Arrhythmias include atrial fibrillation, supraventricular tachycardia, ventricular fibrillation, ventricular tachycardia, atrioventricular block, long QT syndrome, and sick sinus syndrome.

- Polyneuropathy: Diphtheria toxin damages the peripheral nerves.

- Renal failure: The toxin can cause damage to the renal tubules.

- Epiglottitis: Streptococcal or staphylococcal infections cause epiglottitis. It can result in airway obstruction, difficulty breathing, stridor, and cyanosis, eventually leading to death.

- Infectious endocarditis: Infective endocarditis is an inflammatory disease of the inner lining of the heart that primarily affects the cardiac valves.

- Pharyngitis: It is a condition of inflammation at the back of the throat caused by an upper respiratory tract infection. Typically, it causes fever and sore throat. A runny nose, cough, headache, and hoarseness are all possible symptoms.

- Retropharyngeal abscess: A bacterial infection that causes a collection of pus in the back of the throat. Clinical manifestations include swallowing difficulty and pain, fever, stiff neck, and noisy breathing.

- Tonsillitis: Tonsils that are inflamed become red and swollen, resulting in sore throats.

- Foreign body aspiration: Aspirated food can become lodged in the larynx or trachea, causing choking and possibly death.

- Oropharyngeal candidiasis: Candida albicans fungus accumulates on the mouth lining, resulting in white lesions on the tongue or inner cheeks.

Prevention of Diphtheria

Vaccination

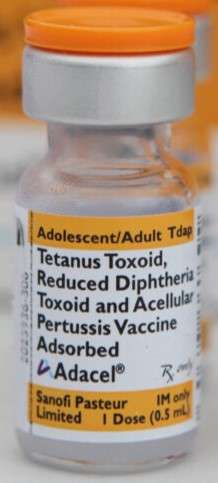

Diphtheria, caused by the bacteria C. diphtheriae, can be prevented with vaccines. Four types of vaccines are ued in the United States to protect against diphtheria, all of which also protect against other diseases like tetanus and pertussis (whooping cough).

- Diphtheria and tetanus (DT) vaccines

- Diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis (DTaP) vaccines

- Tetanus and diphtheria (Td) vaccines

- Tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis (Tdap) vaccines.

Babies and children under the age of seven are given DTaP or DT, while older children and adults are given Tdap and Td.

According to the CDC, diphtheria vaccination is recommended for all babies and children, preteens and teens, and adults.

DTaP vaccine

- 3-dose primary series at ages 2, 4, and 6 months

- Primary series interval of 4 to 8 weeks and minimum interval of 4 weeks

- Boosters at ages 15 through 18 months and 4 through 6 years

- Minimum interval for dose 4 is 6 months from dose 3 and the minimum age is 12 months

Tdap

- 1 dose at ages 11 to 18 for adolescents who have completed the DTaP series

- Td or Tdap booster dose every 10 years for all people

- The Tdap vaccine protects children, adolescents, and adults against tetanus, diphtheria, and whooping cough.

- During the third trimester of any pregnancy, pregnant women should also receive the Tdap vaccine. It is especially important to get the Tdap vaccine while pregnant as the vaccine can protect your baby from whooping cough in the first few months of life.

DT Vaccine

- Diphtheria and tetanus vaccines protect young children from these diseases.

Td Vaccine

- The Td vaccine protects children, adolescents, and adults against tetanus and diphtheria.

Keep Good Personal Hygiene

- Hand hygiene should be practiced regularly, especially before touching the mouth, nose, or eyes; after touching public installations, or when hands are contaminated by respiratory secretions after coughing or sneezing.

- Wash your hands for at least 20 seconds with liquid soap and water. Hand hygiene with 70–80% alcohol-based hand rub is effective.

- Use tissue paper to cover your mouth and nose when you are coughing or sneezing.

- Wear a surgical mask when experiencing respiratory symptoms.

- Increase your body’s immunity by eating a well-balanced diet, getting regular exercise, and getting enough rest.

- Clean the broken skin right away and apply waterproof adhesive dressings.

Maintain Proper Environmental Hygiene

- Clean and disinfect frequently touched surfaces, such as furniture, toys, and commonly shared items, regularly with 1:99 diluted household bleach (mixing 1 part 5.25% bleach with 99 parts water), leave for 15–30 minutes, then rinse with water and dry.

- Wipe away obvious contaminants such as respiratory secretions with absorbent disposable towels, then disinfect the surface and surrounding areas with 1:49 diluted household bleach (mixing 1 part 5.25% bleach with 49 parts water), leave for 15–30 minutes, then rinse with water and keep dry.

- Disinfect metallic surfaces with 70% alcohol.

- Maintain adequate indoor ventilation. Avoid public spaces that are crowded or poorly ventilated.

Prognosis

- The diphtheria prognosis is determined by the severity of the disease and the presence of systemic involvement.

- A poor prognosis is especially associated with cardiac involvement and bacteremia (blood infection).

- The fatality rate for respiratory diphtheria is between 5% and 10%, though it appears to be higher in patients under the age of 5 and over the age of 40 (20%).

- The prognosis for treated cutaneous diphtheria is favorable, with complications and death occurring only in rare cases.

- Diphtheria can be either mild or severe. Some people have no symptoms. The disease can worsen over time. The illness’s recovery is slow.

- The most common causes of death are airway obstruction leading to suffocation and cardiac complications.

Summary

- Diphtheria is a potentially fatal bacterial infection that causes severe inflammation of the nose, throat, and windpipe (trachea).

- Diphtheria is a dangerous disease that can be fatal in 5–10% of cases.

- It is a vaccine-preventable but potentially fatal upper respiratory tract infection.

- The disease can manifest as an asymptomatic carrier, cutaneous infection, or pharyngitis with symptoms such as sore throat, fever, malaise, and cervical lymphadenopathy.

- Diphtheria is treated with an antitoxin, which neutralizes the toxin while also producing long-term immunity.

- To prevent diphtheria, the CDC recommends vaccines for infants, children, adolescents, and adults.

- Since the introduction of an effective diphtheria vaccine, infection and death rates from the disease have been dramatically reduced, making diphtheria a rare disease in many countries.

References

- Lamichhane, A., Radhakrishnan, S.( 2022, Aug 8) . Diphtheria. StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved on 2023, Feb 10 from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560911/

- Otshudiema, J. O., Acosta, A. M., Cassiday, P. K., Hadler, S. C., Hariri, S., & Tiwari, T. S. P. (2021, Nov 2). Respiratory illness caused by Corynebacterium diphtheriae and C. ulcerans, and use of diphtheria antitoxin in the United States, 1996–2018. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 73(9), e2799-e2806. DOI: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1218

- Chaudhary, A., Pandey, S. (2022, Aug 28). Corynebacterium Diphtheriae. StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved on 2023, Feb 11 from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559015/

- WHO. (2018, Sep 4). Diphtheria: Vaccine Preventable Diseases Surveillance Standards. Retrieved 2023 Feb 9 from https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/vaccine-preventable-diseases-surveillance-standards-diphtheria.

- Clarke, K. E., MacNeil, A., Hadler, S., Scott, C., Tiwari, T. S., & Cherian, T. (2019). Global epidemiology of diphtheria, 2000–2017. Emerging infectious diseases, 25(10), 1834. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2510.190271

- Chanh, H. Q., Trieu, H. T., Vuong, H. N. T., Hung, T. K., Phan, T. Q., Campbell, J., Pley, C., & Yacoub, S. (2022, Feb). Novel Clinical Monitoring Approaches for Reemergence of Diphtheria Myocarditis, Vietnam. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 28(2), 282-290. Doi: 10.3201/eid2802.210555

- Center for Disease Control and prevention. (2022, Sep 9). Diphtheria. Retrieved on 2023 Feb 11 from https://www.cdc.gov/diphtheria/index.html.